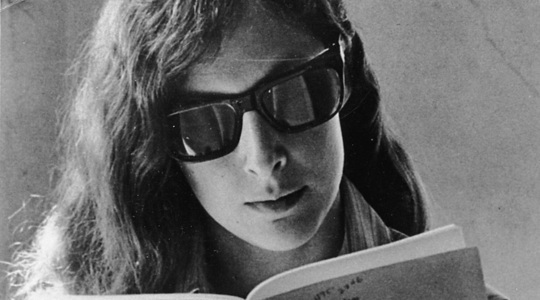

Last Spring, the University of Minnesota Press published Out of the Vinyl Deeps, a collection of critic Ellen Willis’s music writings. Willis became the first pop music critic for the New Yorker in 1968, earning the post on the strength of an essay about Bob Dylan she wrote for Commentary,which caught the eye of William Shawn. She held the post until 1975, filing deeply insightful articles about the Velvet Underground, Elvis in Vegas, Woodstock, and her beloved Rolling Stones.

She was a force in the nascent field of pop criticism, setting precedents that music critics still look to today. But by the mid-’70s, she had become more interested in cultural and gender politics. She mostly abandoned music criticism, writing instead essays about sex, women, and the Left. Many of these essays appeared in the collection No More Nice Girls, originally published in 1992—and now available again from Emily Gould’s e-press Emily Books. Since Willis’s death in 2006, these essays, like her music criticism, have cast a powerful influence.

Bookforum invited three writers who continue to find inspiration in Willis’s work—New Yorker music critic Sasha Frere-Jones, Sara Marcus, author of Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, and Emily Gould—to talk about Willis’s writing and legacy.

EG: I thought we could start by talking about our favorite Ellen Willis essays. They don’t have to be in No More Nice Girls. I will reveal to you that my favorite Ellen Willis essay is, in fact, not in No More Nice Girls, and is actually in Willis’s book Beginning to see the Light.

SM: And what is it, Emily?

EG: “Next Year in Jerusalem.” When Willis’s younger brother decides to become an Orthodox Jew, instead of saying, “Oh, I know for a fact that I have nothing in common with this person anymore, I am ideologically so far from being an Orthodox Jew I can’t even imagine going there,” she decides to test the hypothesis and go to Israel and see whether or not she herself would ever be able to go through a similar conversion process. I think it’s maybe the best personal essay I’ve ever read, and all of Willis’s skills are really on display. She’s a reporter, actually a really good reporter, and she’s very good at writing about herself, and she’s also just a great critical thinker. Those things rarely come together in the same person. Willis questions everything, including her own knee-jerk reactions. And she gets really close: There’s a moment in that essay where she has almost drank the orthodox Kool-Aid and then she has to back away. Her analysis of her own emotional and intellectual state is amazing to read.

SFJ: My favorite Ellen Willis piece is the Woodstock essay in Out of the Vinyl Deeps, but I want to talk about the “Escape from New York” essay in No More Nice Girls.

SM: The Woodstock essay is also in Beginning to See the Light.

SFJ: Right. Beginning to See the Light is a book I first found when I was pretty young. It was sitting around in my house for about two years before I read it, while in college, going through my first attempt at being politically engaged and feeling clumsy. After I read Beginning to See the Light, I was assigned a Willis piece from No More Nice Girls in a film theory class, and kept reading. I eventually hit “Escape from New York,” and it jumped out at me—here was a respected, professional thinker calling bullshit on herself, over and over. It felt like an articulate version of my inarticulate discomfort.

This essay begins with Willis saying, roughly “I’m alone too much. I’m a New Yorker and I’m going to take a bus trip which will force me to confront things,” and she ends up simply being herself over and over again. There’s a great moment where she’s cold and her friend gives her a coat. She writes: “I’m not an impulsive giver. A Marxist might say I’ve been infected with the what’s-in-it-for-me commodity exchange ethic of capitalism.” That’s pretty good, as Marxist references go.

It was powerful to read someone like Willis wondering if she was wrong, constantly doubting her instincts. It was also very New York: She would dissect something very carefully and then shrug it all off with “What do I know?”

EG: She either doesn’t get angry or immediately channels her anger into a different kind of analytical energy. Which is something that I really wish I could do. Reading this book and just being so in it for a month really made me confront what I think is her noble style of argumentation. She definitely isn’t afraid to take on anyone and she can be very dismissive sometimes of people whose points of view she doesn’t agree with. But there’s also what Sasha just mentioned about continually interrogating her own impulses and being willing to revisit points of view that she’s held very strongly in the past. To completely change her mind but still be invested in ethics.

I think there’s a striving in all of Willis’s writing to never be gratuitously mean. Maybe it’s not something she had to work very hard at, but it’s easy to be mean. I think it comes naturally to a lot of writers, myself included. Willis just repeatedly decides not to go there, to take the high road instead and tease out why she wanted to be mean to someone. Then she defeats their argument on a higher ideological battleground.

SFJ: We’ve just seen a number of twenty- or thirty-year-old literary wars being revisited. There was the Didion/Kael swirl, Greil Marcus taking down Renata Adler, and Adler taking down Kael.

Willis was helping construct a kind of popular culture criticism that didn’t exist. Obviously there were critics, but there wasn’t the same fusion of the popular and the academic—people like Raymond Williams and Edmund Wilson worked different beats. There weren’t critics who spoke to general-interest audiences in this way about this stuff. Willis knew that everything in the cultural sphere was potentially serious. Rock and roll did matter.

First-generation critics are always interesting because you are dealing with a cohort who didn’t grow up reading people who held their jobs before them. This isn’t movie critics growing up on five generations of movie critics. The people who turned pop-culture criticism into a job (and a line of inquiry) were involved in politics, theory—all of these other disciplines. They converged and used these tools to form a new way of writing.

These critics were like writers before them in at least one way, though—they were accustomed to having intense disagreements with each other in print. Marcus had a venomously good time attacking Adler, but he took her seriously, as did Adler with Pauline Kael. I think it was a badge of honor to file a lengthy dissection of someone you disagreed with, even if you knew them personally. That was part of the lineage. I wouldn’t say the practice has died, but it’s not happening at the same level.

EG: It’s not as central to the cultural conversation as maybe it was.

SM: I don’t want us to lose sight of the fact that these are two different parts of Willis’s career we’re talking about—not fully separable, but certainly distinct. Her pop criticism was definitely pioneering, and her discourse is different from what we expect from pop critics now. No More Nice Girls collects feminist essays she wrote after quitting music criticism—they’re excellent essays, but they aren’t unprecedented the way her pop criticism was. Her style of argumentation and her discussion of political strategies here is clearly coming out of New Left/SDS stuff. She’s not a pioneer per se of political essaying, but she really was a pioneer of pop criticism—maybe in part, as you’re suggesting, Sasha, by pursuing pop criticism as an element of broader political conversations.

What I find fascinating about the No More Nice Girls phase of her career is that she was publishing this stuff in the Village Voice. There are essays from Social Text, but most of the stuff is from the Voice, and in her book-review essays, she went so much deeper into the arguments of these books than any review we see in weekly outlets now. I love that, and I love thinking about how the Voice in the ‘80s was a weekly newspaper with a wide readership in which Ellen Willis could hold up two books by pro-life feminists and argue about why the conservative backlash to abortion rights was screwed up. She was able to work across so many different boundaries and on so many different levels in ways that I don’t see as options for people who make their living writing anymore.

SFJ: Willis was part of a group that was committed to figuring out what they were doing politically, and how they stood with regard to each other. It was a sustained engagement. These writers would often resolve those differences and sometimes become friends. Maybe not Didion and Kael, but I’m guessing Willis was somebody who probably repaired grudges with people.

SM: And that brings me back to the question about our favorite Ellen Willis essay. I love so many but I’m inclined to choose—even though it’s a pretty wonky one—“Radical Feminism and Feminist Radicalism.”

This was actually the first work of Ellen Willis’ that I ever read. It’s included in the anthology The Sixties Without Apology. I found it when I was doing research for my Riot Grrrl book, and was trying to chart the collapse of culturally revolutionary politics from the ‘60s through the ‘80s. So I came across this Willis essay and found that she had charted out a lot of the things that I suspected were happening during those years, like how both feminism and the left generally had lost their stomach for the cultural fights of the ‘60s and ‘70s; how they had lost their stomach for trying to change the culture of the US. Instead, the left was trying to retrench into a purely economistic fight, as was feminism: there aren’t enough women as CEOs, that sort of thing. This was relatively unthreatening compared with, “We need to change the nature of marriage, we need to change the structure of the family.” Willis talks about it in her book as “utopian imagination.” She sees the ‘80s as an era in which the utopian imagination has failed, especially in light of the not-too-distant ‘60s.

Willis writes about that in “Radical Feminism and Feminist Radicalism,” but what I also found fascinating is how we think we know what radical feminism is until she talks about the rifts between different groups. About how people left this feminist group in New York in 1967 to form this breakaway group, and they fought; about how one group had this line on sexuality and the other group had this other line and the problem with group A’s line was x but then group B’s was hardly any better because they ignored y and z. Willis completely picks them apart from a strategic point of view—when something isn’t working strategically, she’ll see that—but she’s also very interested in whether an argument holds together intellectually.

EG: Do you guys find yourselves aligned with Ellen Willis’s congenital optimism and hopefulness, or do you feel more aligned with what Maggie Nelson wrote in her recent book, The Art of Cruelty, when she says that she used to be really interested in cultural criticism, but now she doesn’t ever want to write about pop culture because she feels it’s like planting a flag on an artificial moon whose purpose is to host flags. And it’s just all covered in flags.

SFJ: That’s a great line. Willis had an interesting story about why and how she shifted. She was writing for other magazines about other stuff and she wrote about a rape case for Rolling Stone.

SM: “The Trial of Arlene Hunt,” which is in Beginning to See the Light. A knockout of an essay.

SFJ: It’s pretty intense. When it came out, the editor William Shawn saw her in the hallway and said, “That was a fantastic piece. Of course, we could never run anything like that, but it was great.” She said she went back to her office and thought about it for an hour and then packed up her things and left. She said she realized then that that’s what she had wanted to do.

SM: He was the one who originally asked her if she would mind writing as E. Willis, right, so that she wasn’t Ellen in print? She said, no, I would mind. I want to be Ellen Willis in print.

SFJ: Yes.

SFJ: She writes maybe ten more pieces about music after that period in her life. It became clear to her that her interests were naturally going somewhere else. When asked about music later on, she said that she mostly listened to the stuff that came out early in her life, in her teens and early twenties.

SM: As tends to be the case.

SFJ: As tends to be the case. But she really didn’t check in again. That wasn’t where her passion was.

SM: I want to plug two things from Beginning to See the Light. Nonfiction writers trying to write good reportage need to read “The Trial of Arlene Hunt,” which is fantastic. The tone is amazing, and it’s chilling and sharp without ever overreaching or overplaying its hand—it’s just straight down the middle. And the intro to Beginning to See the Light is fabulous because it bridges the two phases of her career we’ve been discussing, the initial pop criticism and her writing about politics. Willis talks about how they’re similar. One of the things I love about this intro is her discussion of rock ’n’ roll: She talks about how even if corporate rock ’n’ roll commodifies rebellion, the idea of rebellion is so huge and powerful that the music industry still isn’t able to fully blunt what it means to be listening to music that in its lyrical and musical content is in favor of freedom, in favor of pleasure, in favor of making what you want out of your life. That’s where her optimism enters in a way that is really rare among leftist thinkers. When MTV does a reality show about the Occupy Wall Street protests, it’s easy to think that it’s awful, it’s going to ruin it; but no, it’s not. Ellen was so clear about that. Anything that gets this stuff out into the culture! If we have faith in the power and might of the things that matter to us, we have to believe that they’re going to survive.