When Ishmael Reed gets celebrated these days, now that he’s well past age seventy, it’s usually for the work he did decades ago. The novels that enjoy broadest critical approval are Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down (1969) and Mumbo Jumbo (1972), two comic and surreal historical revisions. Reed was hailed as the great African-American among our homegrown postmoderns (Thomas Pynchon gave him a tip of the cap in Gravity’s Rainbow), if not our foremost black novelist. Esteem like that no longer flutters around his name, but the author himself was the first to shoo it away. He derided such praise as racist.

Racism, for Reed, remains a sickness badly diagnosed. A 1988 selection of essays bore the title Writin’ Is Fightin’, and the opponent in many cases was some crude misrepresentation of African-Americans or other minorities. His argument lies primarily with the media—literary tastemakers, the white conquerors who wrote the history books, and the kingpins of TV and the movies who think they know black experience (recently he lashed out at both The Wire and Precious for their ghetto stereotypes). So he edited the anthology MultiAmerica: Essays on Culture Wars and Cultural Peace (1996), intended as a corrective. So too, with greater energy and less interest in healing, he’s brought out a brilliantly sustained rant of a new novel, JUICE!

The eponymous figure, to be sure, is based on the former running back, currently serving time in Nevada. Note the title’s exclamation point and its all-capital-letter format: What Reed calls O.J.’s “public lynching” provides the novel itself with much of its fuel, or juice. On almost every page, Reed underscores how the media frenzy has gone on years past the man’s acquittal for murder, and excoriates the way constitutional protections were trampled as O.J. became the country’s “dancing monkey” (a quip from O.J. himself, used as the epigraph).

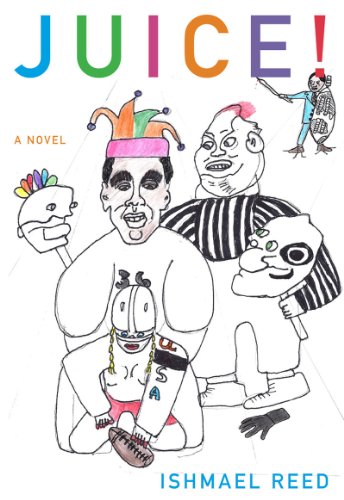

Novelistic subtlety, in other words, has little place. JUICE! is concerned primarily with public life, and its insights are put across with the broad, jagged strokes of a political cartoon. Indeed, the novel’s protagonist draws cartoons for a living, and many passages here are punctuated by his drawings (actually the work of Reed himself, who’s published cartoons since the ‘60s). The artist’s name is Paul Blessings, and he has no connection to Simpson—other than that he’s another successful black American at risk of becoming a “dancing monkey.” His cartoons used to have an edge, a firebrand central character, but now he has chosen to count his small blessings. As the book opens, O.J.’s arrest has set off “the Jim Crow media jury,” and much as this galls the cartoonist, he uses the media as sanctuary. He agrees to produce a toothless weekly piece, featuring the “charming curmudgeonly . . . Koots Badger,” for the TV ratings king KCAK. Like its name, the network’s politics smack of the KKK.

The characters’ names themselves capture the satire that JUICE! liberally offers. The racist who runs KCAK isn’t Rupert Murdoch, or not exactly. He’s B.S. Rathswheeler, and he keeps all the rats running in his bullshit wheel. When Blessings and the token Latina Princessa Bimbette scream at each other about O.J., the racial tensions reverberate hauntingly, wittily, but in the office both remain mere pets.

The narrative also enters the domestic arena, and there confronts issues that would seem to invite psychological development. The cartoonist’s wife is a light-skinned Hispanic, the daughter is experimenting sexually, and Blessings suffers from diabetes. These opportunities for emotional engagement, however, serve Reed only as the chord changes on which he can riff. He rejects conventional character identification; at a moment of family reconciliation, Blessings himself pokes fun at acting “like a protagonist in one of those novels which have been written fiftymillioneleven times.” So too, the cartoonist’s longtime friends, fellow artists and thinkers, function not as individuals so much as in chorus. They echo the general indignation, sometimes delivering the bad news straight: “As long as African-Americans are blamed collectively for the actions of an individual or a few, they aren’t free.”

In the same way, the scenes between friends reveal a defining tic in the point of view, a switch from first person to third. Without warning, Reed confounds the impulse to empathize. He even ruptures the easy connection between main character and author. Toward the end of JUICE! , Blessings lashes out at Reed by name.

The result is a genuinely inventive novel, which depends not on people in catharsis but on the pleasures of the riffing itself, which allows Reed to address, with savvy variety, all the foibles of a country kidding itself about “the world of post-race harmony and sunlight.” Consider, for instance, what one of Blessing’s friends has to say about “mass media magazines:”

[They’re] always putting black gangsters on the cover, but . . . they’ll have long articles about depression, which must be a big problem among their white subscribers. Half their ads are from pharmaceutical companies. I think the two are connected. The showing of black people as the nation’s uglies and the depression of white people. Dissing blacks is like a kind of stimulant for the pleasure centers of their brains. White supremacy is social morphine.

The novel is Reed’s longest, and its heft recalls Isaiah unleashing his visions. It reiterates core elements of its predecessor Japanese By Spring (1993), such as a black sellout, although it’s less contained, a quality that strengthens the book’s effects even as it undermines its character development. Together, in any case, Reed’s late novels strike me as the richest distillation of what he’s about. His critique has gone beyond correcting history, and JUICE! raises his most pertinent warning: Even under a black president, America suffers “untreated racism . . . destroying the country.”

John Domini’s most recent novel is A Tomb on the Periphery. See johndomini.com.