If form hadn’t been a conspicuous problem for philosophers just then and there, the idea of a history of postwar French philosophy as seen on television would seem like a joke. But in the thirty years after the radio broadcast of Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1944 essay “Republic of Silence,” philosophers in France were peculiarly concerned with their changing media. Declaring the book inert—“written by a dead man about dead things,” Sartre wrote in 1947, “it no longer has any place on this earth”—he advised contemporary writers to “learn to speak in images” and to work for newspapers, radio, and film.

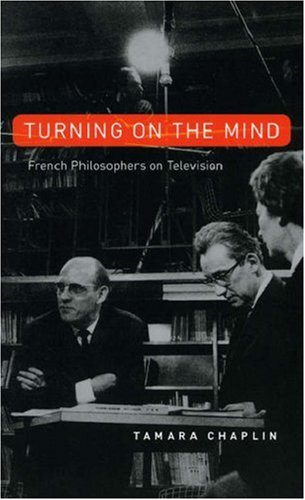

Tamara Chaplin’s vivid, thorough, and irreverent cultural history Turning On the Mind: French Philosophers on Television presents this moment and its consequences from an unfashionable point of view, not that of the editors of Tel Quel, but that of a Parisian couch potato. A historian rather than a critic, she catches facts in their context rather than in her own theoretical web. Her material includes advertisements, memos, and reviews, along with sensitive shot-by-shot analysis of the shows themselves. Most important, she profiles and interviews the people who thought it was a good idea to put philosophy on television: the pompous technocrats, earnest producers, skeptical hosts, and baffled cameramen, as well as the often-inscrutable philosophers.

Like Being and Nothingness, French TV was conceived during the Occupation. In 1943, the Germans launched Fernsehsender Paris, broadcasting “ballet, marionettes, acrobats, clowns, and art exhibitions,” mainly to wounded Nazis in French hospitals. By 1949, two years after Martin Heidegger’s “Letter on Humanism” had announced the end of philosophy, the Vichy infrastructure had evolved into the Radiodiffusion-télévision française (RTF), the agency responsible for running the first, and for fifteen years the only, television station in France. The government saw TV as a pedagogical tool from the beginning. In the early ’50s, for example, in scenes reminiscent of the Terror, French peasants were herded into local télé-clubs—the town cop “proclaimed the night’s program through a tiny bullhorn as he made his rounds, alerting the villagers”—to watch, discuss, and learn.

The first and best book show was launched in 1953, when about .5 percent of French homes (presumably, the richest) had television sets. Lectures pour tous (Reading for All) was hosted by two journalists who had studied philosophy at the Sorbonne, and shot in a style that Chaplin describes, with minor anachronism, as “reminiscent of Godard’s new wave cinema.” (Many clips are available on the website of the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, www.ina.fr.) Sartre’s politics made him virtually taboo at the height of his influence; philosophy was first brought to television by Gaston Bachelard, philosopher of science, space, and reverie, whose provincial origins and flowing white beard made him an unlikely star. (The 1972 television documentary Bachelard parmi nous [Bachelard Among Us]—advertised under the headline “Gaston Bachelard does his own cooking and shopping!”—approaches Us magazine.) Michel Foucault, who appeared on Lectures pour tous in 1966 to hawk his best seller The Order of Things, was good TV for other reasons. He had slogans, like the “death of man”; he was never at a loss for words; most of all, he was an anti-Communist.

Despite ongoing censorship, the decade around 1968—the period when a second television channel was established, the RTF became the ORTF, and the number of French homes with televisions passed the halfway mark—was a fine era for televisual philosophy. L’Enseignement de la philosophie (The Teaching of Philosophy) was briefly hosted by a twenty-something Alain Badiou. The most charming scene in Turning on the Mind is the attempt by the show’s director, Jean Fléchet, to capture “the philosophical event” in the “act of its becoming,” by putting Jean Hyppolite and Georges Canguilhem together in a taxi, where they debate the nature of truth. Another show, Un Certain Regard, surveyed twentieth-century thought, from Rosa Luxemburg and Georg Lukács to Hannah Arendt, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and, most notoriously, in 1974, Jacques Lacan, whose double-episode interview the audience found obscure but inexplicably gripping. Shortly afterward, the oil crisis and subsequent economic reforms brought the ORTF and Un Certain Regard to an end.

The later ’70s and the ’80s are, for the most part, depressing. As television was liberalized, it became less eccentric than it had been under government monopoly. One last gasp was Jean-François Lyotard on Tribune libre, a forum as open-minded as American public access: Under his own name flashing in a vintage computer font, he appeared as several disembodied heads, which referred to him in the third person. But a funny thing happened in the mid-’90s, by which time all the difficult writers were dead or dying: As if in celebration, the nation was seized by a veritable “philo craze,” with an average of four hundred shows on the subject each year. These ranged from La Philo selon Philippe, a sort of Degrassi Junior High set in philosophy class, to talk-show appearances by Michel Serres, who drew 3.5 million viewers. Most of it sounds pretty unctuous, but even bad philosophy is still pretty good television, and the exceptions mentioned in passing do offer some hope to the militant graphocentrist. Unfortunately, they are mentioned only in passing. Maybe the next chapter in the history of the end of the book will have to be written on YouTube.

Sam Stark is an editor at Harper’s.