From the outset, Yaas, the young Jewish Iranian narrator of Gina Nahai’s novel Caspian Rain, is an unwelcome child. The first strike against her is that she is born a girl, and as everyone in her family knows, “there’s nothing but trouble and shame where girls are involved.” Her mother, Bahar, welcomes Yaas into the world with tears of despair, having hoped that the child would be a boy. Instead, she struggles to make do with a daughter. Bahar tries not to have too many expectations for Yaas but can’t help herself. She wants her to succeed where she herself has failed: at being female.

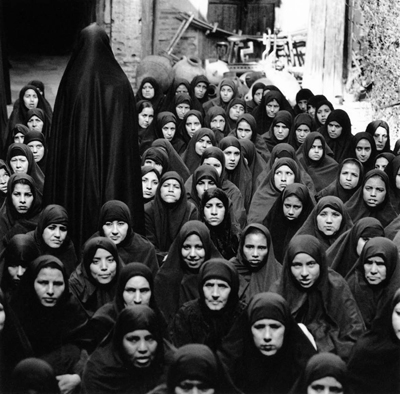

It will come as no surprise to anyone the least bit familiar with Iran that women there have it tough. Journalistic reports detail the stifling conditions under which they live, and ever since the phenomenal success in 2003 of Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, US bookstore shelves have been bursting with memoirs further illustrating the oppressiveness of life in the Islamic Republic. For the most part, this spate of books confirms the widespread belief that women’s freedoms were eroded when clerics seized power in 1979 and reversed the emancipatory policies afforded by the shah. But according to Caspian Rain, this account isn’t entirely true. Even under the debonair, West-emulating shah, the novel argues, women (at least those in certain strata of society) were shackled by their gender.

In the early ’90s, Nahai was one of a handful of Iranians writing and publishing fiction in the United States. Last November, in an article for Publishers Weekly, she recalled that when her first novel, Cry of the Peacock, was released in 1991, bookstores were puzzled about where to file it (since it dealt with Iranian Jews, many stuck it in “Judaica”). But with Caspian Rain, her fourth and most recent book, she finds herself in abundant company. The past year alone saw the release of several novels about Iran and Iranians, including Dalia Sofer’s The Septembers of Shiraz, Nassim Assefi’s Aria, and Porochista Khakpour’s Sons and Other Flammable Objects.

While memoir continues to be the form preferred by Iranian women who left their homeland as young adults (or who never left), the daughters of émigrés, who have grown up in the shadow of their parents’ turbulent past, are finding their own voices in fiction. For this group, memoir perhaps proves ill suited to their personal experiences: Sofer left Iran when she was ten, Khakpour was only a baby when her family emigrated, and Nahai hasn’t set foot in her native country for more than twenty years. Yet their desire to revisit, even fictitiously, the distant nation of their heritage implies a need to make sense of Iran’s weighty history. In her best-selling memoir, Nafisi frequently observes how invaluable fiction was for studying her own culture, and in this way, one of the most celebrated nonfiction books in recent years becomes a testimonial to the power of fiction to capsulate the conditions of an era and to universalize human experience. Although these novels cover different periods of Iranian history and focus on different communities (Muslims, Zoroastrians, Jews), they share a number of themes, such as parent-child relationships, and dwell on the asphyxiating conditions women inhabit. (Sons and Other Flammable Objects is an exception here, but in considering the situation of Iranian men abroad, the novel confirms the irresistible pull of a distant homeland.) More important, the nation these books reveal is one in which women and girls have always been stymied and oppressed.

In Caspian Rain, which is set in the decade before the advent of the revolution, mother and daughter are bound to the same fate: irrelevance. As she grows up, Yaas, whose only way to assert her existence is to engage in a demonstrative act of destruction, is aware that she embodies what her mother “dislikes and resents—the ‘natural disadvantage’ that has made her . . . a person with no options.” Hope, Yaas is reminded as she recounts the story of how her parents met, is a dangerous game. As a young woman, Bahar bristled with optimism. Though her destitute family, which lived one block away from a Jewish ghetto called “the Pit,” insistently believed that “happiness is transient” and “tragedy is what this world was founded on,” Bahar was convinced that she was destined to do great thingsto go to college and teach poetry and literature—and marry a “person of substance.” Reality, however, conspires against her: Bahar does wed a handsome, rich man, but he turns out to be conservative, dismissing her pleas to continue her studies. He’s also unfaithful, carrying on an affair right under her nose, and he readily admits that he has chosen her only because she’s young, “malleable,” and “won’t be hard to train.” Bahar is all of eighteen years old when she resigns herself to this future.

Nahai’s prose is nimble and witty, but the bleakness of Yaas’s and Bahar’s lives and those of Bahar’s hapless mother and sisters—one is deemed an old maid at thirty, the other is repeatedly beaten unconscious by her husband and locked on the roof—entirely contradicts the image of women and of Iran during the shah’s reign as depicted in memoirs. Nafisi, whose mother was among the first women to be elected to the Majlis (Iranian Parliament), explains that “when I was growing up, in the 1960s, there was little difference between my rights and the rights of women in Western democracies.” But in Caspian Rain, wife abuse is common, divorce is out of the question, baby girls are considered liabilities, inheritance money is immediately granted to the male offspring, and children are the father’s possession. In essence, many of the restrictions on women that have come to be associated with postrevolutionary Iran were firmly in place under the shah.

It would be easy to dismiss Nahai’s account of that period of Iranian history as pertaining to only one class of society—poor Jewish women—were it not that Bahar bears so much similarity to Farnaz, the Jewish mother in Sofer’s The Septembers of Shiraz, which is set in Iran after the revolution. In her youth, Farnaz wanted to be a singer and took voice lessons until she turned eighteen, “when her father decided that it was no longer appropriate for a young woman to sing in public.” Of the adult Farnaz, the reader learns that the “dark crescents under her brown eyes” have as much to do with her unfulfilled aspirations as with the brutality of her world—specifically, the ongoing Iran-Iraq War and the aggression of the Iranian regime against its own citizens.

Although Farnaz and Bahar, like Nafisi, married for love (Bahar, at least, thought she had), they can hardly be considered liberated women. With women’s freedoms such a prominent subject in a significant number of books on Iran—and even the impetus behind much of the writing, as well as the publishing and the reading—this discrepancy is worth pondering. Is it the idea of freedom or its reality that is ultimately lost?

Iranians were living under sharia long before the revolution arrived, and Iranian women have been fighting against its male-favorable tenets since the 1840s, when the first women’s organization in Iran was created. According to Nikki R. Keddie’s Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution, the image of the shah as a champion of women’s causes is, if not a falsehood, certainly a less than fully rounded picture: He was “no respecter of women,” Keddie argues, and only promoted emancipation because he came to see “that the encouragement of women in the labor force could help in Iran’s economic growth.” Regardless of the reasons, in 1963 women were finally granted the rights to vote and to be voted into office, and the marriage age was soon raised from fifteen to eighteen. Although by 1977, 33 percent of university students were women, two million women had entered the workforce (many were professionals with university degrees), and several women had been elected to the Majlis, it is also true that many women of that generation, like Bahar and Farnaz, did not or were not allowed by their families or husbands to work. And while the Family Protection Law—which limited polygamy, extended the right to seek divorce to women, and abolished men’s automatic guardianship of their children—was passed in 1967, according to Keddie, “this law was neither totally egalitarian nor universally applied, especially among the popular classes.”

It is often the case in Iran that traditional beliefs, familial shame and honor in particular, are more immutable than laws. Bahar’s father tells her that once she’s married, the only way he will allow her to return to his house is “in a caftan shroud—dead, that is—because we could never live down the shame and infamy of divorce.” “A divorced woman has no rights, no family, not a penny to live on,” he reminds her. But “the stigma of divorce” is a concern for her rich Jewish husband’s family as well. His father won’t let him divorce Bahar to go off with the Muslim woman he’s fallen in love with.

In Caspian Rain, society rather than government functions as the overarching repressive force. The only women who are given free rein—though they are not free of being scorned—are foreigners, such as the daughter of a Nazi couple who resides across the street from Bahar and Yaas, and those who have spent much of their lives abroad and have no familial ties to Iranian society, like the Muslim woman with whom Bahar’s husband is having an affair (she was reared in a British boarding school). For the most part, the subjugation of the female characters in the novel is enforced and propagated by other women, with class serving as the great divider: Elite, cosmopolitan women who read Vogue, smoke More cigarettes, and wear Tufts hairspray and Clinique makeup abhor women of Bahar’s lowly “station.” When Bahar goes to the best tailor in town to be fitted for her wedding gown—an appointment arranged by her haughty future mother-in-law, who refuses to be seen in public with Bahar, as is customary—she is made to wait interminably. The other clients “examine her openly and without pretense, even talk about her out loud with one another,” and the supercilious Armenian seamstress pokes and shoves her repeatedly. This experience is a hard-won lesson for Bahar; from that moment on, “she will always remember . . . how she was attacked and belittled by a woman who should have been helping her.”

Whereas before the revolution, many of the restrictions on women were (as they continue to be in neighboring countries) determined by class, religious affiliation, and the conventions of specific communities, soon after Khomeini seized power, all women were forced to abide by the strictest interpretation of Islamic law. The Family Protection Law was fitfully discarded by the clerics, who declared it contradictory to Islamic beliefs, and women once again found themselves second-class citizens, whose value, in a court of law, was half that of men.

The Septembers of Shiraz powerfully depicts the toll the new regime takes on Farnaz and her daughter—who, at age nine, is old enough to be married—by taking up the issue of enforced veiling, which went into effect in 1980. Even though some of Khomeini’s supporters were Muslim women who believed in the sanctity of sharia and were happy to see Islamic tenets reinstated, for the droves of secular and non-Muslim women who participated in rallies to topple the shah and encouraged the return of Khomeini, in the belief that he would guarantee the rights of women as promised, the new regulations were a betrayal. In donning navy slacks, a white turtleneck, and a long black coat before going out, Farnaz finds herself denied her selfhood and femininity and suddenly powerless. “Her shapeless reflection in the full-length mirror strips her of the one lure she had possessed before the days of the revolution,” Sofer eloquently writes, “when a hip-hugging skirt, a fitted cashmere sweater, and a red smile were enough to get an entire room of a house painted for free, or the most tender meat saved by the butcher.”

Soon after they established themselves in their governmental posts, the clerics locked down the borders, turning Iran into a prison shut off from the rest of the world. Farnaz often reminisces about her old cosmopolitan life and the parties she attended with her husband, including the coronation of the shah, with chefs from Paris and young musicians from Vienna or Berlin. She also loved to travel and is unable to contemplate a life without her many souvenirs: “These objects, she had always believed, are infused with the souls of the places from which they came, and of the people who had made or sold them. . . . Living among these objects assured her that hers was a populated world.” Farnaz is so attached to her artifacts that she refuses to leave Iran without them when she has the chance. But like the many Iranians who were likewise preoccupied with their cherished possessions, she comes to recognize these items as unimportant trifles, especially in a country that has little appreciation for relics or historyeven its own.

In beautiful and tempered prose, Sofer, whose own Jewish father was jailed and accused of being a spy, weaves the story of Farnaz and her daughter together with that of her son in New York and her husband, Isaac, locked away in Tehran’s infamous Evin Prison. Although the inmates in this fictional account are all male, there were and are many women sent to Evin, as evidenced by two recent memoirs by women who served time there—Marina Nemat’s Prisoner of Tehran (2007) and Zarah Ghahramani’s My Life as a Traitor (2008). It is interesting to read these books, which portray the incarceration of two young women some twenty years apart, in conjunction with The Septembers of Shiraz. One finds not only many thematic parallels—including the distrust of friends and loved ones instilled by the regime and the hypocrisy and corruption of the revolutionaries, once prisoners and now torturers—but also shared descriptions of the treatment of inmates: lashing of the feet, blindfolding, and interrogation. Women are not spared torture and execution; only in prison are they accorded equality with men. In The Septembers of Shiraz, the arbitrariness of the arrests is reflected both in Isaac’s story and in that of the alluded-to female cellmates. One of the prisoners has three daughters in prison: “One for being a communist, one for being an adulteress, and the third for being their sister.”

In Sofer’s novel, politics shape the characters’ lives from the first paragraph—when the Revolutionary Guards arrive one morning to arrest Isaac as he tends his shop —to the last, and the family must flee their homeland in order to escape the government’s random brutality. For men and women seeking freedoms, emigration is the only answer. (Today, an estimated one million Iranians reside in the United States.) And yet, as Assefi’s novel Aria demonstrates, even when a woman is American born, she is still expected to adhere to the Islamic society’s rules, and the creeds of shame and honor abide. The novel, which unfolds in a series of correspondences, tells the story of Jasmine Talahi, an Iranian-American oncology professor, who, to the dismay of her parents in Iran, cohabitates with her American boyfriend and chooses her career over marriage. Jasmine’s father refuses to communicate with her; her mother sends chastising letters, urging her to repent her sinful ways. Jasmine refuses to fulfill their wishes, and her mother renounces her. When the young woman attempts to contact her parents after the death of her five-year-old daughter, her letters go unanswered. Grief-stricken and unmoored, Jasmine sets out on a world-wearying spiritual journey, à la Paulo Coelho. Unfortunately, the novel here becomes a travelogue, and the reader must endure Jasmine’s tedious accounts of trips to several countries before she finally arrives in Tehran, where she is greeted by some forty-seven relatives. She spends most of her days in “this otherwise uninspiring capital city” at home, flocked by visitors who have come to offer their condolences. Initially, this suits her: “Inside the privacy of my parents’ home, I do not have to face the fashion police . . . the suffocating pollution; aggressive drivers with their constant honking; and bored groups of men who are eager to harass a lone woman as she passes.” But when she ventures out, craving privacy and solitude, she is accosted by the men of the “morality squad,” who are alarmed at the sight of an unaccompanied woman roaming the streets.

Most of Assefi’s observations are perfunctory and in keeping with the Iran familiar from news reports and other books. Her portrait of the two teenage daughters of a childhood friend, however, reflects a different, generational attitude toward the regime’s sanctions. The girls watch counterfeit copies of the film As Good as It Gets, read contraband fashion magazines, obsess over Madonna and the Spice Girls, speak in English slang (they say “Ouch!” when they encounter a steep price), and regard the processions of men flagellating themselves during the bloody Day of Ashura as an opportunity to flirt with boys and collect phone numbers. As Azadeh Moaveni notes in her 2005 memoir, Lipstick Jihad, and in recent dispatches from Iran for Time magazine, these young women—more so than their parents, who experienced difficulty in adjusting to the restrictive laws—know no other life and find ways to circumvent the rules.

Unfortunately, the theme of the inherent tension between a first-generation Iranian American and her parents, which is announced at the beginning of Aria, is dropped when Jasmine arrives to visit them. Suddenly, they become loving; they embrace and welcome her, and all is forgiven. Such absolution is harder to come by in Porochista Khakpour’s novel, the quirkily titled and quirkily written Sons and Other Flammable Objects, which also explores the relationship between parent and child, but in this case, it’s between a father (Darius, who lives in California) and his estranged son (Xerxes, in New York). The two female characters, Darius’s wife, Lala, and Xerxes’s girlfriend, Suzanne, may be Iranian but are hardly typical as such. Lala happily left her wretched country and changed her Iranian name, Laleh, into the American-sounding variant. Aside from this, Khakpour omits any explanation of how Lala’s childhood in Iran formed the woman she has become. Suzanne, one-eighth Iranian, has never traveled to the country, and her vision of it is naive, at best: She imagines it as a place of unique gemstones, hookahs, palm trees, cobblestone streets, and pomegranate vendors—an Eden where she and Xerxes can walk around “holding hands through the bustling chaotic streets . . . she just another one of the women covered in a delicate black draping.” Misconceptions about Iran are also promulgated by Suzanne’s parents, who are horrified at the thought of their daughter heading into such ungodly territory. “The country’s just another nail in the Mid East coffin!” her mother exclaims. When Suzanne explains that she has timed a trip to coincide with Persian New Year, her mother replies, “All you kids want to do is . . . party for New Year’s! Well, I tell you what, missy, in that country I don’t even think they do that.” This sardonic tone resonates throughout Khakpour’s narrative, implying that such ideas are mere nonsense, yet the author never bothers to indicate just how far-fetched or untrue these pronouncements may be, and since Suzanne never makes it to Iran, the reader is never given the chance to counter her imagined country with the real one. Nor is it ever explained how an unmarried woman would be allowed to travel to Iran with her boyfriend, let alone how they will be able to spend time together in public as they tour the country.

Faraway Iran looms large throughout the book, haunting its characters, especially Xerxes, who finds himself unable to “escape his birthplace even stateside.” His parents refuse to discuss their lives back home, and yet Iran is always there, inhabiting all the silences, all that is unsaid, a tragedy of untold proportions. Regardless of how much or how little Iranian parents reflect on the loss of their homeland, that sense of loss is inevitably transferred to their children. These novels are the product of the children of the immigrant generation; Iran continues to both define and elude them, and fiction provides a vehicle to explore that distant and tumultuous country. Contemporary Iran in particular remains elusive. For those writers based in America, it is a recent history they have not experienced. For now, the task of chronicling present-day Iran is left to the novelists who reside there.

In Reading Lolita in Tehran, Nafisi said, “I have a recurring fantasy that one more article has been added to the Bill of Rights: the right to free access to imagination.” When she wrote these words, shortly before emigrating in 1997, there were few women novelists in Iran. But soon after, the situation changed: The first best-selling novel by a woman, Drunkard Morning by Fataneh Haj Seyed, was published in 1998, and today, female writers are numerous and thriving, besting their male counterparts in both output and success. According to a New York Times article, there are about four hundred women writers in Iran, thirteen times as many as a decade ago. Whereas only five thousand copies are issued for the average Iranian novel, some women’s books have had print runs of a hundred thousand or more. Much of this is the result of the changing cultural landscape: Women now constitute more than 60 percent of college attendees and more than 30 percent of the workforce—and, as such, are quickly becoming an influential constituency—and in 2001, a bill was passed allowing unmarried women to travel abroad for graduate education. The legal age of marriage remains thirteen years old, yet few women are married this young; the average age is twenty-two. And despite the risk of imprisonment or beating, women continue to demonstrate for equality and justice.

The Iranian female literary voice has existed since the early nineteenth century (in the 1930s, there were some fourteen women’s magazines that discussed women’s rights, veiling, and education). In the past decade, writing, both in journalistic outlets and in literary form, has become a powerful tool for raising awareness about the plight of the Iranian woman. Nevertheless, as throughout contemporary Iranian history, women’s rights continue to seesaw. The recent mass arrests of dissenters, including the much-vilified incarceration of female activists demanding the abolition of lashings and stonings, and the crackdown on “immodest” dress (of men as well as of women) could very well stall the women’s movement that has been building over the past few years. Iranian writers, unhindered by censorship and persecution in the United States, are seeking to define themselves, as well as the meaning of their national identity. As Nahai has noted in regard to the sudden proliferation of books on Iran in America, “Iranian women are writing, I imagine, because they live in a place and at a time when they can speak the truth without fear of morbid consequences,” adding, “I think exile has been so good for Iranians, especially for the women.” The late Edward Said, himself an émigré, reflected that “in the United States, academic, intellectual and aesthetic thought is what it is today because of refugees from fascism, communism and other regimes given to the oppression and expulsion of dissidents.” And yet, while expatriate fiction has been for the most part the domain of male writers (Nabokov, Huxley, Auden, and so on), this wave of Iranian women writers is charting a new literary voice—one by women and, for the most part, about women. While much of this writing dwells on a collective heritage, these authors, through their vigorous self-reflection, simultaneously propose a new Iranian woman, one who just may escape the past.

Nana Asfour is on the editorial staff of the New Yorker and writes frequently about Middle Eastern culture.