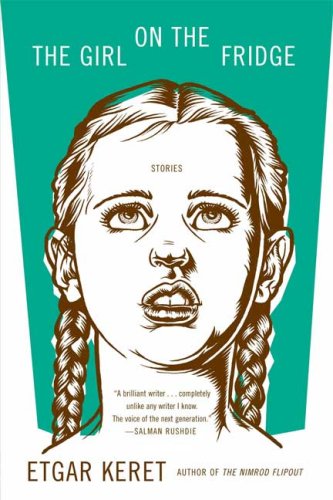

We, Brave New World, 1984, A Clockwork Orange: These classics of dystopian fiction provide relief from their grim predictions only because they are predictions. The worlds the books portray are far in the future and thus, it is implied, preventable. Not so with Etgar Keret’s latest collection of disturbing yet hilarious short stories, The Girl on the Fridge. The dystopia that this Israeli writer presents is no imminent nightmare; it’s a reflection of the everyday irrationality and suffering in Keret’s homeland and elsewhere. And though this reflection is as fragmented as the world it depicts—forty-six absurd scenes that range in length from a paragraph to a few pages—the pieces add up to a blindingly meaningful whole. The gist: Life will screw you up, but at least you’re still here to tell your story.

Reading Keret’s collection is a little like sitting at a bar next to a guy who is telling his story, unbidden and relentlessly. “I was stressed out all through the show,” says the magician narrator of “Hat Trick.” “I couldn’t get in the zone. I fucked up the Queen of Hearts trick. All I could think about was the hat.” The staccato sentences, colloquial speech, and self-obsession—elements in all of the stories—lend the character that stranger-in-a-bar feel, but it is the magician’s perplexity that, more than anything else, marks him as a sad, lost, lonely soul. In trying to understand why, when he reached into his hat one day, he pulled out not a rabbit but a bloody rabbit’s head, and another day, a dead baby, he can only surmise that “it’s as if someone was trying to tell me this is no time to be a rabbit, or a baby.”

Many of the book’s narrators display a similar bewilderment. In relating their tales of violence (a brokenhearted man uses a sledgehammer to kill a maniac, who is running down the street stabbing people at random), alienation (a woman spent her childhood on top of a refrigerator because her parents had no patience or energy to deal with her), and loss (a friend stands at the grave of his army buddy, reminiscing about their drinking days), the characters in these vignettes attempt to work out how they’ve come to live amid such banal horror—and how they’ve endured.

Invariably, their methods are grim and unsettling, as are the stories themselves. So unsettling are they, so ambiguous and maddeningly suggestive, that initially you might find you don’t like them (and in fact, the first six or so tales are the weakest, cartoonish and lacking the nuance of some of the later ones). But as with the guy in the bar, if you stick with them, you’ll experience unexpected insights—into the nature of pain and humor and the power of the short, short form—and, in the best stories, moments of startling truth.