What is the purpose of your writing?” a Muslim friend asks V. S. Naipaul in his 1981 landmark book on the Islamic world, Among the Believers. “Is it to tell people what it’s all about?”

“Yes,” Naipaul replies, “I would say comprehension.”

“Is it not for money?”

“Yes. But the nature of the work is also important.”

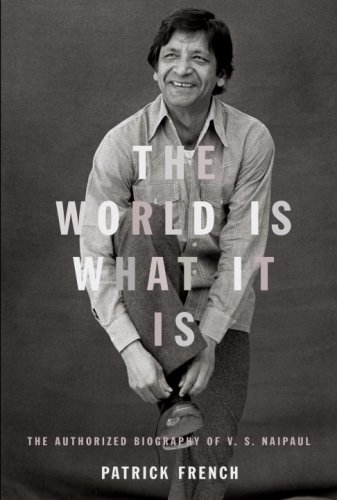

The nature of the work and its author are the subjects of Patrick French’s extraordinary biography, The World Is What It Is. French calls the huge undertaking “perhaps the last literary biography to be written from a complete paper archive. His notebooks, correspondence, handwritten manuscripts, financial papers, recordings, photographs, press cuttings, and journals . . . ran to more than 50,000 pieces of paper.” French appears to have made use of every scrap.

Certainly the prospect of writing it must have been daunting. Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul has arguably been the most important writer in the world for more than three decades, or at least, as V. S. Pritchett told Newsweek in 1980, “the greatest living writer in the English language.” (The 2001 Nobel Prize seemed to most like an afterthought.) His productivity has been amazing, with at least thirty-three volumes of fiction, essays, memoirs, and, for want of a more precise term, travel books. French has handled an immense amount of material with a deft hand, and the reader actually wishes he had extended the book’s 487 pages of text and pursued his subject past 1996, where the book ends with a terse “Enough.”

Released by Naipaul’s own publisher, The World Is What It Is (the title is taken from the famous first sentence of 1979’s A Bend in the River) is authorized but not compromised. Presumably, Naipaul chose French for his knowledge of terrain Naipaul himself had traversed, revealed in Younghusband (1994), a sturdy biography of the British Edwardian explorer, and Liberty or Death (1997), a clear-eyed account of India’s struggle for independence and its aftermath. If Naipaul thought that he could intimidate French or that French would be awed in the presence of the master, he was mistaken. The subject, writes French in the introduction, “has stuck scrupulously to our agreement; I have had no direction or restriction from him. He had the opportunity to read the completed manuscript, but requested no changes.” That is a breathtaking thought for one to keep in mind while reading. Progressive education has taught us that great men are not necessarily good men; it’s the work that’s important. But it’s difficult to reconcile the writer who has always shown (regardless of what one thinks about his politics) an enduring and steadfast sense of justice and decency with the cold-blooded monster of ego revealed in The World Is What It Is.

The revelations about Naipaul’s first marriage alone are enough to make one queasy. His wife of forty-one years, Patricia Hale, learned from a 1994 New Yorker interview with Stephen Schiff that her husband had been “a great prostitute man” early in their marriage. At the time, she was undergoing treatment for breast cancer, and she would die just two years later. “It could be said that I had killed her,” he told French. “It could be said. I feel a little bit that way.” For most of her married life, she struggled to live up to Vidia’s dictum “You don’t behave like a writer’s wife. You behave like the wife of a clerk who has risen above her station.” Her husband’s work, French concludes, “became a substitute for living.” Naipaul continued to use Pat as a sounding board for his most recent manuscript even as she was virtually on her deathbed—but he proposed to his second wife before his first was dead.

Naipaul was faithful to his promise to supply French with all the available material. He turned over an entire collection of letters from his longtime mistress, Margaret Murray. (One wonders what Murray’s reaction was on learning from this book that some of her letters were unopened!) He also gave French Pat’s diary, apparently unread by Naipaul himself; it’s a source French regards as “an essential, unparalleled record of V. S. Naipaul’s later life and work, [which] reveals more about the creation of his subsequent books, and her role in their creation, than any other source. It puts Patricia Naipaul on a par with other great, tragic, literary spouses such as Sonia Tolstoy, Jane Carlyle, and Leonard Woolf.” Clearly, the biographer’s sympathies are with his subject’s late wife, and how could they not be? As French writes on the breakup of the famous friendship between Naipaul and Paul Theroux, the American writer “failed to see that Naipaul had no loyalty to him.”

Friendship, it seems, is no higher on Naipaul’s list than loyalty. In 1971, he told an interviewer that never having to work for anyone “has given me a freedom from people, from entanglements.” He told French, “I was not interested and I remain completely indifferent to how people think of me, because I was serving this thing called literature.”

Serving literature, apparently, does not mean helping other writers. When Salman Rushdie was under sentence of death from the Ayatollah Khomeini, Naipaul refused to join in his defense. “I don’t know his books,” he said, “but I’ve been aware of his statements. I found them usually left-wing and trivial and antiquated.” Khomeini’s fatwa, he quipped, was “an extreme form of literary criticism.”

It’s hard to see how French could have been more objective if his subject had been dead for ten years. About the only humanity the book reveals in Naipaul lies in the fact that he allowed it to be written. But why, exactly, did he? Possibly because someone (notably Jeffrey Myers, correctly dismissed by French as “a serial producer of books and articles”) was going to write one anyway, and he felt there was no point in a biography that wasn’t absolutely candid.

“The lives of writers,” said Naipaul in a 1994 speech, “are a legitimate subject of inquiry; and the truth should not be skimped. It may well be, in fact, that a full account of a writer’s life might in the end be more a work of literature and more illuminatingof a cultural or historical moment—than the writer’s books.” What does this mean? Naipaul seems to be saying that a biography can be a greater work than any produced by its subject, and while that is certainly possible in the cases of midlevel writers such as William Somerset Maugham and Pearl Buck, it’s hard to believe that Naipaul could ever consider that any biography of him would be more illuminatingof any cultural or historical moment—than his own books.

Born (as he has reminded us countless times) in Trinidad in 1932 (“I thought it was a great mistake,” he told Bernard Levin in a 1983 interview), the young Vidia became alienated from the Hindu culture and religion of his family at an early age. Hindu caste is patrilineal, and though he inherited “the implied ‘caste sense’” of his mother’s family, he claimed to reject it; his father’s background, he reported, was “confused in my mind.” Actually, he would embrace little of his island’s culture, no matter from which ethnic group. In a 1958 edition of the Times Literary Supplement, he described Trinidad as “a simple colonial philistine society,” and as he would later reveal in The Middle Passage (1962), he rejected just about everything from his homeland, including steel bands, “a sound I detested,” and the annual Carnival, which “has always depressed me.”

At school, “he made no deliberate effort to associate with other Indians. . . . He never brought friends home.” He explained to French, “You wouldn’t want another boy to see your poverty.” Having few indigenous writers to inspire him, he latched on early to O. Henry and Maugham, though his primary inspiration was his father, a capable journalist who wrote for a local English-language paper. When asked decades later by an Indian website for some rules for aspiring writers, Naipaul made suggestions that echoed his father’s instruction: “Do not use big words. If your computer tells you that your average word is more than five letters long, there is something wrong.” “Never use words whose meaning you are not sure of. If you break this rule you should look for other work.” “Avoid the abstract. Always go for the concrete.” Vidia has followed the latter advice as if it were sacred.

In 1950, he won a scholarship to Oxford (where one of his professors was J. R. R. Tolkien). He fell in love with a fellow student, Patricia Hale, daughter of working-class parents from Birmingham. The affair didn’t prevent fits of depression that worsened “even as his intellectual understanding and his literary ability grew.” It was, as Naipaul later described it, “a very bad period, the long, long summer with my questioning myself internally night and day, every waking minute, that great depression.” Finally, he “dressed for the occasion,” put on a suit he wouldn’t mind being caught dead in, turned on the gas, and lay down on the bed. French refers to the incident as “a poor man’s Russian roulette: the gas fire worked on a coin-operated meter, and he would lie there until it ran out. . . . As he lay there in his suit, the gas ran out. He took this as an omen.” He put off further suicide attempts, telling himself, “Pat is coming to see you next week.” She believed in his literary ability even when he did not; he scraped by with assorted journalism jobs, including writing for and broadcasting the BBC’s Caribbean Voices. In 1957, at age twenty-five, his first novel, The Mystic Masseur, was published to generally good reviews (though a critic for the New Statesman thought it “yet another piece of intuitive or slaphappy West Indian fiction as pleasant, muddled and inconsequent as the Trinidadian Hindus it describes”).

Condescendingly dismissed as one of the “calypso novelists” who were putting “colour and punch into British writing,” Naipaul would be respectfully relegated to the ghetto of regional author until the early ’70s, by which time his body of work—swelled by the great travel books The Middle Passage, An Area of Darkness (1964), his first India book, and The Loss of El Dorado (1969)—made him impossible to ignore. Both literally and figuratively, he had gone where no British or American writer had before him.

French is so thorough that it’s likely no further biography of Naipaul, at least one covering the first sixty-odd years of his life, will ever be needed. But a biographer of a great writer must be a great critic if his book is to last. French is very good on Naipaul’s writing; not so good as, say, Richard Ellmann on James Joyce’s, but then French has much more material to appraise.

He handles the major works of fiction well. In a Free State (1971), comprising four narratives—three stories, and a prologue and an epilogue linked to create a fourtheach reflecting a different aspect of Naipaul’s life, is “a disconcerting piece of writing, so taut and ambiguous that the author’s point of view is never apparent.” A House for Mr. Biswas, the novel inspired by Naipaul’s father and one of his few works of fiction infused with genuine humor, was, at the time of its publication in 1961, “not enough to carry him through; postcolonial literature had yet to be invented as a genre or as a profitable business, and his work remained an anomaly. Later, set against novels such as Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe or Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, A House for Mr. Biswas would be seen as a seminal postcolonial text.” A Bend in the River, the book that would forever link Naipaul’s name with Joseph Conrad’s by turning Heart of Darkness inside out, showing the colonial experience from the colonists’ perspective, is “a book which brought together all his experience and the uniqueness of his perspective, a late twentieth-century global narrative that could have been written by no one else.”

Though he doesn’t say it, French seems to feel that Naipaul the novelist might never have been widely read if not for Naipaul the traveling journalist; after all, it wasn’t until the ’80s, when he became known for his nonfiction, that his books began to earn serious money. “I am,” as he once famously wrote of himself, “the kind of writer people think other people are reading,” and the books people think other people are reading by Naipaul generally fit the description Theroux proffered in a mean-spirited review of Half a Life (2001), written after their friendship had ended: “great reviews, poor sales, and a literary prize.” (Though Theroux neglected to mention that the prize often increased sales.)

No one who has read his two most acclaimed novels, A Bend in the River and A House for Mr. Biswas, and perhaps three or four others, including The Mimic Men (1967), Guerrillas (1975), and The Enigma of Arrival (1987), would deny that Naipaul is a major writer of fiction, but for many his nonfiction is his greater achievement. Ezra Pound once said that literature is news that stays news. Naipaul’s news has stayed news.

“We read,” Naipaul wrote in his much-quoted essay on Conrad, “Conrad’s Darkness and Mine,” “to find out what we already know,” but many American readers turn to Naipaul precisely to find out about what they don’t know—the colonial West Indies, India, Congo, Perón’s Argentina, the Islamic world. To explore these civilizations, Naipaul invented a new kind of literature: In J. M. Coetzee’s words, he “pioneered an alternative, fluid, semi-fictional form,” books not influenced by previous writers but stemming from his own experience. In a tone often described as magisterial—authoritative without pomposity—he took us to the strife-torn suburbs of the world, stripping them of their illusions and our illusions about them while restoring their vitality and strangeness. Unclouded by Marxist sentiment, Naipaul submitted the pretensions of governments, political systems, and politicians on several continents to his powers of synthesis and analysis. Those pretensions withered in his wake.

Perhaps nowhere has Naipaul been so controversial—or so prescient—as in his pronouncements on modern Islamic states, exemplified by his statement in Among the Believers that

this late-twentieth century Islam appeared to raise political issues. But it had the flaw of its origins—the flaw that ran right through Islamic history: to the political issues it raised it offered no political or practical solution. It offered only the faith. . . . This political Islam was rage, anarchy.

This book cemented his worldwide reputation. Naipaul, says French, “was reviewed as a writer at the height of his powers, investigating mysterious lands with a ruthless, encircling eye. Unlike novelists who wrote about Islam after 11 September 2001 and took refuge in jargon, pretending they knew what hadith or tajwid meant despite having minimal or no experience of life in Muslim countries, he concentrated on his own observation, and avoided reading too many books. Vidia’s interest was less in Islam than in Muslims, in what they thought and did in the countries he visited.” A passage from British journalist John Carey, quoted by French, describes Naipaul’s method: “He wanders around, chatting with students and taxi-drivers, munching dried fruit and nuts, asking mild but pointed questions. . . . Even when his conclusions are hostile, he never lacks sympathy.”

Naipaul has been savaged by critics such as H. B. Singh (who called him “a despicable lackey of neo-colonialism and imperialism”) and Edward Said (“a kind of belated Kipling who carries with him a kind of half-stated but finally unexamined reverence for the colonial order”). Nonetheless, Naipaul has demonstrated something that no pundit can offer, remarkable empathy and sympathy with third-world people. Institutions, not individuals, have always been his targets. And while he shares a fealty toward colonial culture with Kipling, Naipaul is capable of doing what Kipling could not: turning the same scathing vision on Western culture.

An Area of Darkness, for instance, chastises India not for its inability to produce art but for its failure to see it from an Indian perspective: “It is still through European eyes that India looks at her ruins and her art. Nearly every Indian who writes on Indian art feels bound to quote from the writing of European admirers.” And yet “to know Indians was to take a delight in people as people; every encounter was an adventure.”

Naipaul’s unique literary sensibility, at once both compassionate and austere, has no antecedents. In his Nobel lecture, he said, “The young French or English person who wished to write would have found any number of models to set him on his way. I had none.” The nearest thing to a literary influence he had as a boy was his father, and when he went to study at Oxford, he was close to being an intellectual blank slate. He would pretty much remain one throughout his life: Twentieth-century literature as a whole seems to have made little mark.

If there is one thing missing from The World Is What It Is, it’s a detailed account of the author’s intellectual and literary evolution; my guess is that’s because there wasn’t one. As a writer, the adult Naipaul seems to have sprung out fully formed, like Athena from the head of Zeus. His writings contain few references to the greatest writers of the twentieth century—scant mentions of Joyce (he once referred to Ulysses contemptuously as “the Irish book”), Kafka, Woolf, Faulkner (except a passing note in his surprisingly prosaic account of his 1989 tour of the southern states, A Turn in the South). More to the point is his complete lack of interest in twentieth-century critics of colonialism, such as Camus and Orwell.

Though some scholars have seen The Enigma of Arrival as revealing the influence of Proust, Naipaul has called the greatest French novelist of the past century “tedious” and “self-indulgent.” Enigma’s obviously autobiographical protagonist confesses “boardinghouse life might have meant more to me if I were better read in contemporary English books . . . in spite of my education, I was under-read.” About the only twentieth-century writers he seems to approve of wholeheartedly are Maugham and Evelyn Waugh, whom he was “much influenced by” in his teenage years. (Waugh praised some of Naipaul’s books in print but, in a letter to Nancy Mitford in 1963, referred to him as “that clever little nigger Naipaul [who] has won another literary prize. Oh for a black face.”)

Naipaul, in his literary sympathies, is strictly a nineteenth-century man, expressing a kinship with Balzac, Dickens, and Tolstoy, but the more challenging and innovative European prose writers of the century leave him cold: Stendhal, he told an interviewer, was “repetitive, tedious”—as his dismissal of Proust suggests, “tedious” seems to be regarded by Naipaul as a prime literary insult—“infuriating,” while Flaubert was “the greatest disappointment.” He has claimed, at various times, to find no merit in Henry James.

Naipaul, it appears, will brook no literary rival from any century. His insulting public references to Gabriel García Márquez, a writer of far greater imaginative gifts and one of the third-world novelists who has given new life to the novel—a form Naipaul has declared long dead—seem like petty jealousy, while E. M. Forster, who had the audacity to write a novel called A Passage to India, was branded “a sodomite” and an “odious fraud.” Worst of all has been his refusal to acknowledge his debt to Conrad, whom in his famous essay he berated for “his own imaginative deficiency as well as his philosophical need to stick as close as possible to the facts of every situation. In fiction he did not seek to discover; he sought only to explain”—surely an indictment that applies to both Naipaul’s fiction and his nonfiction.

“His public position,” French writes, “as a novelist and chronicler was inflexible at a time of intellectual relativism: He stood for high civilization, individual rights and the rule of law.” What Naipaul once wrote of Conrad may well be true of himself: “Perhaps it doesn’t matter what we say about Conrad; it is enough that he is discussed.” The World Is What It Is adds depth and clarity to the discussion of Naipaul’s work. It does not “explain” V. S. Naipaul, nor does it seek to; “the commonplace that a biographer has found the ‘key’ to a person’s life,” French concludes, “is implausible. . . . The best a biographer can hope for is to illuminate aspects of a life and seek to give glimpses of the subject, and that way tell a story.” French has met his own rigorous standards and, one feels, Sir Vidia’s as well.

Allen Barra is the author of Inventing Wyatt Earp (Carroll & Graf, 1998).