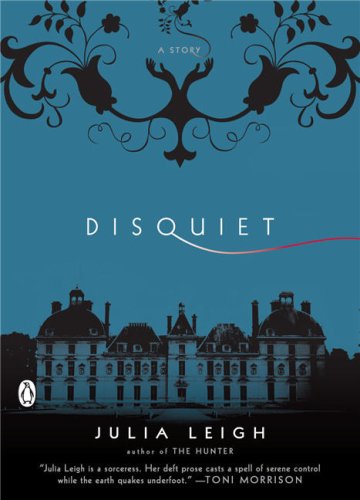

It has been eight years since Australian writer Julia Leigh’s debut novel, The Hunter, was published in the US to warm reviews. The length of this interval makes the brevity of her second book, Disquiet (described as “a story” on its cover), all the more notable. Both works have fundamental similarities: dysfunctional families made brutal by trauma; remote, fablelike settings; and the theme of survival. But the hostilities of the wild in The Hunter have been replaced by the savagery of the domestic.

Disquiet at first has a slow-burning, foreboding atmosphere. It opens with Olivia and her two young children, Andrew and Lucy, forcing their way into the gardens of an isolated château in the French countryside. Having traveled from Australia to escape an abusive husband and father, they are greeted frostily by Olivia’s mother, who has been awaiting her son, Marcus, his wife, Sophie, and their newborn baby. This second group arrives with a small bundle—the corpse of the stillborn child, which Sophie insists on carrying and trying to feed until she can bear to bury it.

While they prepare for the baby’s funeral, the family members participate in a series of ghoulish and unwholesome activities. The corpse is kept in the freezer and lets out “foul-smelling squeaks” as it decomposes; Andrew darkly asks his grandmother, while she is holding a cat, whether he can “stroke her pussy”; Sophie breast-feeds her philandering husband in the dead of night; Andrew watches Marcus masturbate while on the phone with his mistress. One imagines that such information is intended to hint at the psychological damage the characters both suffer and inflict, but these vulgar details tilt the story dangerously close to farce.

This may be deliberate, for the book’s style shifts constantly. Sections written in an annotative manner (“Through the window: evening star”) are disrupted by extended expositional dialogue, and wonderfully poetic, terse language (“her tiny earbones vibrated with the tripped-up thud of her heart”) is interspersed with sentences made dull by colloquialisms (“Time—there was no time, never had been—what a joke”). It is difficult to tell whether the characters are idiosyncratic or symbolic (Olivia is referred to by name and as “the woman”; similarly, her children are named, universalized, named again). Generally, the gothic setting floats free of the exigencies of the time-bound world, making the occasional reference to cell phones, giant plasma screens, or jetlag jarring.

Disquiet’s title suggests the author’s intention. However, the tale ends up being unsettling for the wrong reasons: not because of its insights into human depravity or into the communicative limits of trauma and suffering, but because Leigh seems uncertain of her voice. The reader is too often in the same boat as her omniscient narrator describing Andrew after he glimpses the corpse in the freezer: “Maybe he saw something maybe he didn’t, maybe something accounted for his mother’s reaction or maybe it didn’t.”