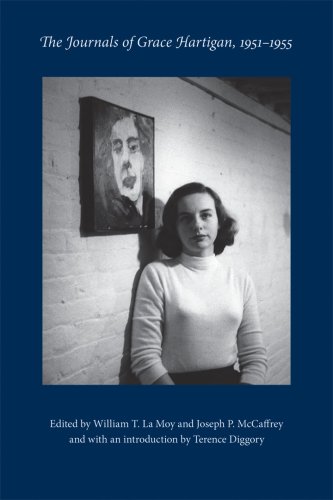

The wonderfully vivid photograph of the young Grace Hartigan on the cover of her newly published Journals takes me back to the time more than half a century ago when I first encountered the artist and her work. She had come to Vassar in 1954 to give an informal talk in conjunction with her solo show at the college art gallery. Ten years younger than she and an inexperienced instructor at my alma mater, I was immensely impressed with the power of her painting and just as excited by the forceful exoticism of her persona. She seemed so bold, so transgressive and self-assured, so inimitably “downtown” amid the dowdy tweeds of Poughkeepsie, New York. She used curse words with casual familiarity and talked confidently about painting and the problems of painting, just as the ideas came to her. It is therefore surprising to discover in the pages of Hartigan’s journal a very different woman: She was then reading Virginia Woolf’s Diaries “with oh such tenderness, as though she were myself. How she did fret over the world and what it said of her.” Hartigan was clearly more vulnerable to public opinion than she let on.

Hartigan’s journal, which she kept from 1951 to 1955, five of the most productive years of her career, should be considered an example of a specific literary genre, with its own tropes and figures, rather than an un-mediated source of the “truth” of an artist’s life. Hartigan’s writings also served a therapeutic function. But most interestingly, they record, with the utmost precision, the seismic ups and downs of her own estimation of her work. On May 6, 1953, she writes, “I believe the Bathers is finished, I’m trembling with excitement over it. In some ways I think it’s the most important picture I’ve ever painted.” The next day she contradicts herself: “I was wrong about Bathers, there is much more that it needs. I’ve been carried away by these momentary enthusiasms before—I must try to remember to be more hesitant in the future.” Later the same day, however, she asserts, “This time it’s really finished. I almost feel as though I can’t take any credit for it. I worked on it all morning in a blind, inspired heat, every thing went right. In color especially it is one of the most bold & brave pictures I’ve ever done. I still can’t believe I did it.” And on the next day, May 8, she is again highly positive: “‘Bathers’ looks good this morning. I think for the first time I am using color as a powerful structural element. As a result this picture looks ‘French’—but who else has used color but the French?” This leads her to more general thoughts about painting: “I’m sick of this American provincialism anyhow, childish reflections of all the lessons we can learn from European art.” But she then turns to the impact of a specific artist: “‘Bathers’ owes a great deal to Matisse, he has always been my master. I am more & more interested in a very formal classical art, but an art which is also filled with a sense of irony.”

The artist’s journal has a long history in the modern era, starting famously with Delacroix’s in the nineteenth century. Hartigan’s is a fine example of the type, with its combination of exaltation and depression; constant worry about money, prices, and payments or the lack thereof; complaints about fellow artists; snide or admiring comments about friends (often poets or literary figures); frequent, penetrating accounts of what she is reading (Rilke, Frank O’Hara, Woolf, Jacques Barzun on Berlioz) and what she is looking at (Goya, Picasso, Matisse, de Kooning); discussions of fraught relationships; worries about art-world politics; and harsh words about unfriendly critics like Clement Greenberg.

Yet Hartigan’s journals are most distinctive for being the written record of the experiences of a woman artist at a time when the status of women artists was ambiguous, to say the least, and internally and externally different from that of male peers in the New York art world. Although Hartigan was an accepted and often admired member of the so-called second generation of Abstract Expressionists, with important shows and critical approval, she occasionally complains about her treatment as a woman artist and is ambivalent about being one herself. For instance, in an entry from April 25, 1951, referencing two of her paintings, she declares: “Aries and 6² seem tremendously feminine in their color—which of course I detest.” A longer entry on December 3, referencing a gathering at her friend Helen Frankenthaler’s place, is more explicit about her awareness of her position as a woman artist—and her rage about how it is used against her:

At Helen’s Saturday with the Pollock’s, Clem, Barney Newman and [Friedel] Dzubas. Clem got on his kick of “women painters.” Same thing—too easily satisfied, “finish” pictures, polish, “candy;” said Al, Larry and Goodnough all struggle. Makes me realize how alone I am. Am I to scream at him “I struggle too, I do! I Do!” He said he wants to be the contemporary of the first great woman painter. What shit—he’d be the first to attack.

The very fact that she identified herself as George Hartigan in her first three exhibitions might seem like a canny abandoning of her feminine identity for a better chance in the marketplace, but she maintained that “George” referenced two of her heroines, George Sand and George Eliot, who had taken the name in the nineteenth century. At other times, Hartigan seems valiantly self-assured about her status as a woman artist, and proud of it, even while being aware of the rampant prejudice against her because of her gender: “John spoke of a show that the Club will hold at the ‘Stable’ galleries, and they want to include Al, Dzubas and Goodnough from De Nagy, altho they will consent to use Rivers. I felt depressed by this discrimination, for I think I deserve to be chosen. . . . I refuse to become involved or feel persecuted over these things, my doubts are great enough already without heaping on extra coals of fire. I believe I am the first woman of major stature in painting, and I feel that given a long life and sufficient courage and energy, I may become a great artist.” This last claim is as unequivocal an acceptance of her identity as it is possible to imagine—although Hartigan wisely refuses to equate being the first woman of major stature in painting with being a great artist tout court.

At other times, her rage against authority (read: male authority) takes the form of public explosions against what she identifies as “deadness” or “lack of feeling” but what feminists of the ’70s were to denominate “the Patriarchy.” “I also have resigned from the [artists’] Club,” she writes in an entry from December 17, 1952.

Friday night I created a small scandal by completely losing my head and accusing the [all-male] panel . . . of being boring and pedantic, and stating that Greenberg no longer wrote art criticism because he has nothing more to say. I was livid with rage & almost incoherent, I could have said many better things if I had been more objective, but this has been storing up for a long time, this revolt against deadness and lack of feeling (Also against “authority” I must admit.) Whenever I go there I am either bored to deadness or filled with frightening aggressions. Since I don’t care for either extreme the only solution is to burn all my bridges behind me and not return.

But these incursions into what might be called a protofeminist self-confidence and a rebellion against the status quo are relatively rare in her journal. Hartigan is more apt to like or dislike other women’s art more or less at random. It is not until the late ’50s and early ’60s that she sustained meaningful and mutually supportive friendships with other women—namely, Frankenthaler and poet Barbara Guest. During this time, Hartigan painted an unusual series of self-portraits, the “Pallas Athena” series, under the influence of Guest’s classical enthusiasms and the work of the feminist poet H. D. and embarked on a collaborative print series, inspired by classical themes, in conjunction with Guest. Yet all this lay in the future. Hartigan stopped keeping her journal in 1955. The last complete entry is from July 21: “I’m going to let this sit and jell for a while, there may be more I must do to it, I don’t know.” But the journal actually ends with a fantastically provocative incomplete sentence: “Observed from the window a wonderful creature to.” Then follow the remnants of eighteen pages of entries that Hartigan cut out and destroyed. We are left to wonder what the wonderful creature might have been and what was in that sizable chunk of journal the artist felt it necessary to suppress.

Linda Nochlin is Lila Acheson Wallace Professor of Modern Art at New York University and the author, most recently, of Bathers, Bodies, Beauty: The Visceral Eye (Harvard University Press, 2006).