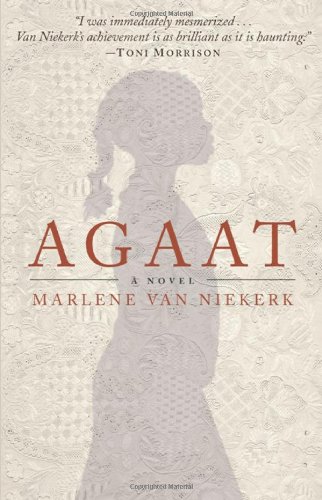

Few books I’ve read carry the visceral impact of Marlene van Niekerk’s Agaat; it is the South African writer’s second novel and fifth book, and it is stunning. Set in the apartheid era of the 1950s into the ’90s, on a dairy farm contentiously run by a desperately unhappy white couple, Milla and Jak de Wet, and their half-adopted, half-enslaved black maid, Agaat, it is about institutional racial violence, intimate domestic violence, human violence against the natural world, pride, folly, self-deception, and the innately mixed, sometimes debased nature of human love. It is especially about how this mixed nature is expressed through the deep and complex language of the body; I don’t believe I’ve ever read a book that so powerfully translates this physical language into printed words.

Agaat is narrated almost entirely by Milla, a strong-minded, verbally sophisticated, emotionally bereft Afrikaans woman paralyzed in old age by a motor-neuron disease, unable to communicate except with her eyes, and only then to Agaat, with whom she long had an anguished and loving bond and who cares for her on an all too intimate level. Here, for example, is Agaat cleaning Milla’s mouth:

Say “ah” for doctor, says Agaat. I close my eyes. What have I done wrong? The little mole-hand nuzzles out my tongue. . . . The screw has squashed it in my mouth. My tongue is being staked out for its turn at ablution. The sponge is rough. With vigorous strokes my tongue is scrubbed down. . . . Three times the sponge is recharged before Agaat is satisfied. My tongue feels eradicated.

Then:

Her fingers move more gently, more kindly on my gums. Then it becomes caressing. Forgive me, ask the fingers, I also have a hard time with you, you know.

And then:

More passionate the movement becomes. Agaat curses me in the mouth with her thumb and index finger. Bugger you! I feel against my palate, bugger you and your mother. . . . She takes her hand from my mouth. . . . She wipes my face, the tears from my cheeks. Thank you, I signal briefly. You’re welcome, says Agaat.

The relationship is loaded not only because it is mutually dependent and (at least socially) unequal but because years ago Milla, as a charity project, rescued the five-year-old Agaat from a viciously abusive family and began to nurture her with methods both harsh and kind. Against the scornful judgments of her husband and everyone else, Milla falls in love with the child, whom she raises as a daughter. But there is simply no place in the world of apartheid for such a relationship to exist, and Milla cedes to this reality by gradually teaching her beloved girl her “place,” that is, reducing her to a kind of privileged servant. When Milla gets pregnant, she ruthlessly cuts Agaat out of her heart (or tries to), all the while believing her behavior is noble.

Agaat’s servitude is made complete by her own instinct for love, and when Milla compels her, at the age of twelve, to deliver the baby when they can’t make it to a clinic in time, we feel this servitude being driven into Agaat’s core—and paradoxically joined with what will become her power over Milla, particularly Milla’s body:

You talked fast, emphasized the main points. Water. Breath. Push. Head. Out. Blood. Slippery. Careful. Slap. Yowl. Bind. Cut. Wrap. Bring to. Wash. . . . If the little head can’t get out, she has to take the scissors and cut, you said, to the back, do you understand? towards the shitter, she had to cut through the meat of your arse, so that he can get out. Saw if necessary, she mustn’t spare you. If he’s blue, she has to clean his nose and wipe out his drool, out from the back of his throat and from his tongue and blow breath into him over his nose and mouth until he makes a sound. As we do with the calves when they’re struggling. She can leave you, you said, even if you’re bleeding something terrible, it doesn’t matter.

These instructions given to a young girl who was so severely raped before her “white step-mother” found her that she can’t have her own child.

But it is also Agaat’s instinct for love that allows her not only to survive but to enact a revenge that is equal parts tenderness and rage and that is as lifelong, exacting, and daily as her servitude—the emotional theft of Milla’s child, Jakkie, who grows to love Agaat more than he does his brutal father or convoluted mother.

Then there is a more subtle revenge, subtle because it comes about accidentally and in part out of a simple desire to understand and communicate: While Milla lies paralyzed and dying, Agaat finds and begins to read aloud the diaries Milla kept largely to chronicle what she thinks of as “the Covenant” between her and the abandoned girl whom she sought to make “human.” Milla cringes to hear her “unconsidered writing” forced “down [her own] gullet,” and with reason: She is thus made to confront the self-flattery, dishonesty, and heartlessness that she blinded herself to when she was younger—and that she is now too broken to deny. She is so overcome with shame that she fails to see that the diaries also reveal a good, even ardent woman warped by a twisted society, a profoundly cold family, and an abusive marriage, a woman whose impulses toward love are simply no match for the internalized pathology of her environment.

That Agaat does see all this only makes it worse for her. For it is difficult to say which is more terrible: that Milla’s love is warped by her enmeshment in the social system around her or that it is on a private level very pure, especially when she is first earning the little girl’s trust. For example, when she is coaxing Agaat to speak for the first time:

Then I bent down and whispered in her ear. . . . I’m so hungry, I’m so thirsty, I said, because you don’t want to talk to me and I know you can talk. . . . Perhaps you can say your new name for me? I blinked with my eyes to ask, big please! . . . Why is it taking me so long to write it up? I’d rather just think about it again and again. It’s too precious! It’s too fine! Words spoil it. Who could understand? . . . I imagined the tip of her will as the rolled-up tip of a fern. Did I say it out loud? That she should also imagine it? A tender green ringlet with little folded-in fingers? I bent it open with my attention. Then it came into my ear, like the rushing of my own blood, against the deep end of the roof of her mouth, a gentle guttural-fricative, the sound of a shell against my ear, the g-g-g of Agaat. . . . Then we said her name at the same time. Sweet, full in my mouth, like a mouthful of something heavenly. Lord my God, the child You have given me.

Yet it is this child whom she will later describe as a “little snot-skivvy,” whom she will as a matter of course betray to the cruelty of white outsiders, whom she will humiliate both deliberately and indifferently and at least once physically punish to the extent that even her racist husband remarks that he’s sick of being an “extra in [her] concentration-camp movie.” (This behavior is especially grotesque because of the extreme social circumstances that shape it. But far from being exclusive to South Africa, it is all too recognizable as the way human beings treat one another in every context imaginable.)

In the last pages, van Niekerk frees us from Milla’s tortured head and we hear from Jakkie, now grown and living in Canada, in a state of “mourning [as] a life-long occupation.” As close as he once was to Agaat, he has come to see her as an “Apartheid Cyborg. Assembled from loose components plus audiotape,” as ruined as his parents have been by his country’s inhuman system. After the intense emotionality of his mother’s narrative, this cold, sorrowing assessment is welcome. Yet . . . he calls this “Cyborg” his brown mother, and it is through him that we finally hear Agaat’s voice telling him the secret story she told every night, the story Milla was never allowed to hear.

In revealing this much of the plot I am scarcely giving away the story, because it is van Niekerk’s telling that makes it extraordinary. The author’s terrible entwining of intimacy, deep physical understanding, abuse, disregard, and real affection—the tension between the will to cruelty and the will to love, between the social machine and the small beings that must live within its strictures—cycles relentlessly through the story, taking us to a more devastating place of understanding with each turn. In Agaat, each dichotomy—love, sorrow, purity, shame, betrayal, fidelity, goodness, and brute political will—is equally and tragically real.

Mary Gaitskill is the author, most recently, of the story collection Don’t Cry (Pantheon, 2009).