The first Led Zeppelin song I ever loved was “D’yer Mak’er,” one of the cheesiest tunes the band ever recorded. To make things worse, I used to pronounce the title “Die-er Make-er” instead of “Jamaica.” Obviously, I wasn’t a Led Zeppelin fanatic. I grew up a metalhead in Queens, New York, in the 1980s and worshipped bands like Anthrax and Slayer. The only time I really noticed Zeppelin was when 92.3 (K-Rock!) would run some ridiculous commercial where a dude with a deep voice would shout, “Get the Led Out Weekend!” I’d quickly turn that oldies bullshit off.

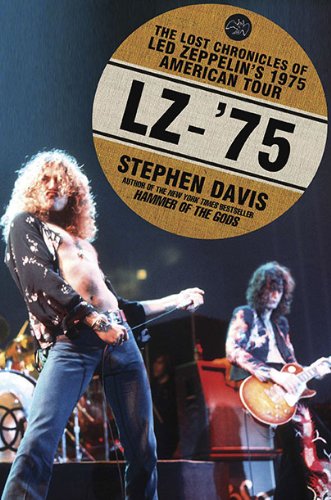

Stephen Davis, the author of LZ-’75, doesn’t seem to feel the same way. This is actually his second book about the band. His first, Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga, was released in 1985 and became a big best seller. It’s a chatty, awestruck book that’s clearly interested in both history and legend. Here, for example, are the first two sentences: “The maledicta, infamous libels, and annoying rumors concerning Led Zeppelin began to circulate like poisoned blood during the British rock quartet’s third tour of America in 1969. Awful tales were whispered from one groupie clique to another, as Led Zeppelin raided their cities and moved quietly on.” Despite my less than fervid attachment to the band, I read Hammer of the Gods two decades ago and remember it fondly. Tales of young men who strike it rich and have sex with boatloads of women? Yes, please! But the publication of another book about Led Zeppelin, this one a chronicle of the band’s American tour in 1975, does raise the question, What else is there to say?

In the prologue, Davis explains that “Led Zeppelin rarely let journalists anywhere near the band.” He chalks this up to the negative attention of condescending music critics, as well as to the tantrums of thin-skinned band members who didn’t appreciate criticism of any kind. In 1975, Led Zeppelin were “the biggest, highest-grossing rock band in the world, as well as the booming music industry’s biggest act. The records shipped platinum. The tours sold out in moments. . . . But in 1975, the mainstream media didn’t play along.” Zeppelin were about to release a new album, Physical Graffiti, and the insatiably ambitious band, having already conquered the rock world, wanted more. As drummer John Bonham said plainly, he and his bandmates were determined to reach “the people that don’t know about us.” This meant the mainstream press would have to be courted. Magazines like Rolling Stone, no fans of Led Zeppelin, would be invited backstage and on the road, even on board the band’s private Boeing 727, Starship One. As Davis writes, with more than a little pride, “I was one of those writers.”

From January to March of 1975, Davis traveled with Led Zeppelin. The band paid for everything, a point that seems to have given Davis no pause at all. To be fair, though, while other writers were working for commercial music magazines like Rolling Stone and Creem, Davis was reporting for the Atlantic Monthly. Yes, that Atlantic Monthly. A detail like this, which Davis offers with an appropriate flourish of humor, is the first sign his book will offer the reader pleasant surprises. Davis kept his notes in three notebooks. After the tour ended, he came home, put them in a drawer, and forgot about them. He didn’t find them again until 2005. This book is based on those notes.

Davis calls 1975 “the top year for the band.” Tragedies, waning musical powers, and the end of the group followed. Under such circumstances, Davis could have treated these unearthed notebooks with reverence appropriate to the Dead Sea Scrolls, but thankfully, he doesn’t. In fact, LZ-75 goes some way toward dispelling the magic aura that surrounded the band—the kind of glamour, indeed, that Hammer of the Gods helped to create. And that’s why this book is such a pleasure.

Most folks love to believe in magic. Even the most hard-nosed realist may cling to the myth of genius. I’m talking about the Good Will Hunting type of genius, which tends to discount hard work and study, except maybe in a two-minute montage. The infamous deal with the devil is the music world’s version of this nonsense. Robert Johnson, blues legend, is said to have sold his soul to the devil in Mississippi in return for mastery of the guitar. As opposed to, you know, making a living as an itinerant busker, practicing constantly, and learning at the feet of blues legends like Son House. Led Zeppelin were also said to have sold their souls to Satan, in return for phenomenal success. Circumstantial evidence—like founder and guitarist Jimmy Page’s habit of prancing around in wizard costumes and his decision to buy the former home of renowned occultist Aleister Crowley—only helped the legend grow. But Davis’s book just barely hints at another explanation.

Early in LZ-’75, Davis flashes back to 1968 and mentions a gig he attended at a club called the Boston Tea Party. The newly formed Jeff Beck Group was in town performing from its first album, Truth. Davis was watching Beck and Ron Wood tune their guitars before the show when he spied “two figures sitting in a dark corner,” one enormous and the other slender, clad in velvet, and with long dark hair. The pair turned out to be Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin’s notorious manager, and Page. “Jimmy was joining the Beck tour for a few days to check out the reaction of the American kids to the new, guitar-heavy rock bands emerging from England.” This wasn’t the Jimmy Page of the stage persona, dragon king of the mystic arts—instead, this moment offers a glimpse of James Patrick Page, already a seasoned musician and consummate businessman, out on the road doing field research in order to see whether there’s a market for his product. Not selling his soul to the lord of the underworld, just maybe to Mammon.

Davis’s winning account goes on to humanize many of the mythic figures in the band—none more than lead singer Robert Plant, who was only twenty-seven in 1975. While Plant was already incredibly famous, Davis manages to make him into something more interesting: a kid with something to prove. At one point, we learn he was enormously happy with a favorable review of the band in London’s Financial Times because it was the paper his father, an accountant, read. Even though Plant’s father disapproved of his son’s rock career, the boy could still hope that a positive mention in a salmon-colored investors’ broadsheet might mean something to the man. Elsewhere, we see Plant at pains to point out to anyone who will listen that his wife is Indian. (She was half.) When Plant and Davis sit down for tea with a photographer, the singer sounds like a child who’s learned a few new words and can’t stop saying them. “‘Chai?’ Robert leaped up. ‘Let’s have some chai. My wife’s Indian, you know.’”

Davis extends this same methodical, demystifying attention to detail to the band as a whole. Early on, LZ-’75 reads like a catalogue of lousy performances: bad singing, poor sound systems, lackluster guitar solos, and “the long, long cocktail jazz stylings of J. P. Jones [their bassist] during his big nightly showcase.” But rather than tarnishing the Zeppelin myth, this kind of stuff only makes me admire the band more. When Davis describes devastatingly accomplished performances toward the end of the tour, I actually believe him, because he’s shown how hard the band worked to get there. Lots of trial. Lots of failure. It’s not magic—it’s chemistry.

LZ-’75 is a quick read, the kind of thing you can gulp down in an afternoon. For all his reconstruction of the fateful tour, Davis doesn’t dote too much on band minutiae (though he does indulge that fanboy impulse a bit, here and there). And sometimes he can sound like he’s writing ad copy for the band rather than reporting. But these moments pass quickly, especially since most chapters are only a few pages long. And when he takes his focus off the band entirely, he offers endearing portraits of some peripheral characters. There’s Peggy Day and the Prairie Princess and even a sweet note from a kid who missed a concert because “I had my 4-H heifer project due the next day. (We took second place. My heifer’s name is Cheeseburger.)” Davis intuits that the godlike depictions of Bonham, Jones, Plant, and Page can be as silly as those old K-Rock commercials were. (“This weekend we’re only pumping Ledded!”) He understands that the most interesting thing to talk about now is how a few hundred thousand people got together to enjoy some great music in 1975. He makes it sound like a damn good time.

Victor LaValle’s latest novel, Big Machine, was published in paperback by Spiegel & Grau this year.