A mutual friend once told me that the most important thing to know about Andy Cohen—the Bravo exec, on-air late-night host, and Real Housewife wrangler—is that his parents loved him very much. He grew up kind, and expecting good things from the world.

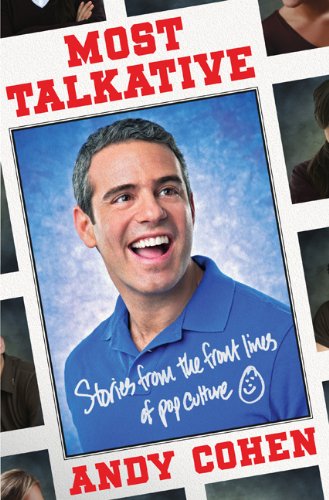

Now he’s published—and it actually does sound like him, unlike most ghosted popcult memoirs!—a gushy, messy memoir-to-date, Most Talkative: Stories from the Front Lines of Pop Culture (Henry Holt, $25). (He is forty-four.) Topics include his growing up in St. Louis, his extreme gayness, his loud mother, his struggles to acknowledge his extreme gayness, his adoration of pop culture (from Susan Lucci to the B-52s to Diana Ross to Bette Midler to everything in between, which . . . not sure there is much of an in-between there, is there?), his years in the news biz, his devotion to All My Children, and, as it goes on, the drama of the Real Housewives franchise. Those last, silly events are already barely memorable, and, like their protagonists, they surely won’t age well. (Or will they? Playing the “what if aliens landed and read only one book?” game with this one is both intriguing and terrifying.)

Writing a memoir for the now is rarely a good idea. But it’s necessary: Holt, Cohen’s publisher, surely believes that a promise of hot inside gossip will move some books to the kind of people who wonder what it’s like to be near a buxom, deranged reality star. So do remember down the road: Nielsen BookScan doesn’t count sales at Walmart and Sam’s Club, where such info in book form can best connect with a wildly distant yet still wealth-aspirational class. (What’s that? I can hear the typing of Cohen—whom I should disclose is among my Facebook friends, or, you know, “friends”—already writing a stern e-mail about the high average household income and the college education of the Bravo demographic.)

What the book does not contain is a single peep about Cohen’s adult love life—pretty much my sole interest while reading. (He is a fox, and extraordinarily magnetic.) And there’s a very nice downplaying of membership in the world of fame and in the milieu of the New Lavender Mafia. Cohen did go work for Barry Diller, who gets maybe two scant references, and he does refer to Anderson Cooper once as a friend. But that’s pretty much it, and even his acknowledgment pages are curiously free of celebrity name-dropping. He’ll have his fifties to get jaded and crass; right now he’s still in transition from star-struck loudmouth.

It’s sweet that Cohen is so in touch with gawky adolescence. His book is adorable in its loud forthrightness—it’s a cute look for his brand. Also his programming is quite good at helping America gorge on its own destruction. And he’s smart, so he’s fully capable of talking convincingly about reality TV as documentary, as sociology, even as how we understand class in America. It’s far more likely, though, that people watch Bravo’s wildly successful reality franchises in the same way that monkeys stare at more famous or successful monkeys. Status anxiety isn’t exactly class consciousness.

Still, here’s yet another thing that’s surprising. In an episode in his long career in soft-hard news, Cohen wrangled three shoots a day in Oklahoma City in the wake of the bombing for CBS—but was exceedingly grateful to have bolted the network a year before 9/11. (“I had the best time at CBS News until I stopped having an amazingly fun time, and that’s when I went and got a new job,” Cohen told me in an interview back in 2009.) He’s right to be relieved that he left, and his September 11 reminiscence is one of the more honest and instructive things I’ve read about that day:

If it was even remotely possible to feel grateful for one thing about 9/11, besides just being alive, it was that I didn’t have to find the people who had hung those flyers and interview them about whether or not they still held out any hope. I didn’t have to sit in an editing bay trying to make a piece work, looking for that certain something that would elevate it over everyone else’s 9/11 pieces. . . . And while I had never felt worse before, at least I didn’t have to try not to.

Circa the mid-’90s, Cohen writes, TV’s already quite vapid soft-news format “got lighter.” True! He did some time at 48 Hours, then went to Trio, the network that lasted all of five years in America. He didn’t go down with that ship, but was invited to follow his boss in hopping over to Bravo in 2005, to “run current programming.” Cohen was then desperate instead to take over the new gay network Logo, but didn’t even get a callback after his interview, so to Bravo he went.

Bravo, it’s almost impossible to remember, was originally packaged as an “arts channel,” featuring a lineup of sturdy, if rarely viewed, high-culture performance fare. (Would it be fair for me to mourn its early premium subscription days, when I rarely if ever watched it? But come on: A mainstay was Jazz Counterpoint!) The network’s new core team began arriving in 2002 and solidified in 2004–2005; then the Real Housewives franchise vomited forth in March of 2006. We have had six years of Housewives. Dick Cheney only ruled America for eight! It feels like their time should be over, and yet, late last year, episodes were setting ratings records.

Still, their time will come. There is a dark moment at the end of the book. Cohen’s beloved All My Children comes to an end, and, like Carrie Bradshaw before him, he’s forced to wonder: “Was I, in some way, partly to blame for this? Had I helped kill soaps?” Well, yes, pal, you absolutely did. So take heart in the logic of tragedy, America: At least Andy Cohen’s more depraved productions caused him some anguish along the way. It’s not the way hubris is punished in classical Greek dramas, but hey, Bravo hasn’t aired any of those since the mid-’90s.