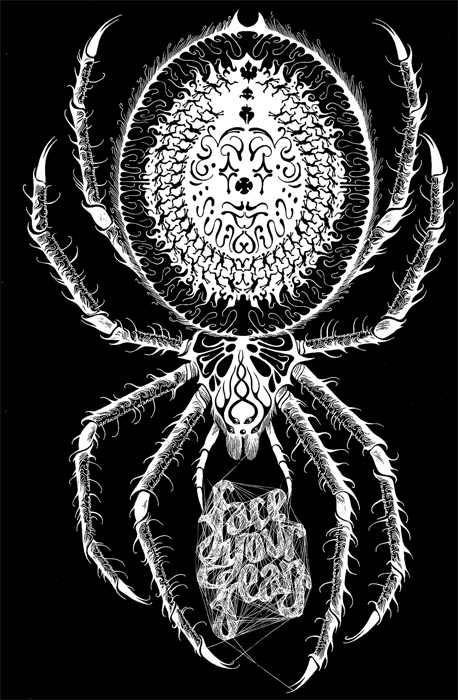

The title of MARIAN BANTJES: PRETTY PICTURES (Thames & Hudson/ Metropolis Books, $75) projects a William Morris–like faith in the decorative, as well as an ironic awareness of that concept’s toxicity for modernists. The Vancouver-based artist’s 2010 collection, I Wonder, amply displayed her design virtuosity: letterforms growing swirls and curlicues, like a figure skater’s trail on ice, and intricate border and background designs, assembled in a gorgeous—if a bit airless—small-format volume. Her thumping new fourteen-inch-tall monograph, in which Bantjes looked after every detail, allows her designs the breathing space they need. The pleasure of untangling her complex visuals is enhanced by a text—revealing, no-nonsense, critical, and, at times, brash—in which well-earned self-esteem is barely concealed beneath a bushel of Canadian modesty.

With its classy cloth half-binding and alternating pages of coated paper (for images) and delicate uncoated stock (for text), TOM DIXON: DIXONARY (Violette Editions, $50) quickly defeats the initial impression that it’s an overproduced product catalogue. The self-taught Dixon started out in the early ’80s making what could only be called punk chairs, welded and wired together from scrap metal, before he evolved into Britain’s most resourceful furnishings designer. The chronologically organized Dixonary juxtaposes each of Dixon’s designs with an image, often fanciful, representing some aspect of what sparked the idea, from Roxy Paine to bicycle chain, hand grenade to Gene Krupa’s drum kit. His breakthrough success, the S chair, was inspired, he says, by a doodle of a chicken on the back of a napkin.

In KARA WALKER: DUST JACKETS FOR THE NIGGERATI (Gregory R. Miller & Co., $45), the artist, assisted by the design firm CoMa, has cleverly folded the dust jacket into a large artwork that includes her entire foreword and a full-scale detail of a large text piece. The fine reproductions include these boldly graphic works as well as her powerfully kinetic figurative drawings. Walker’s art engages with historical forms of American popular entertainment, from minstrel shows, vaudeville turns, old movies, and nightclub acts, to public lynchings with postcard souvenirs. Conceiving its images as “potential covers for unwritten essays, works of fiction, and missing narratives of the black migration,” Walker transforms the art book from coffee-table objet to black-and-white bomb.

Charles Marville was lucky enough to be present with a camera during the creation of modern Paris, from Baron Haussmann’s demolition of “Vieux Paris” in the 1850s to the destruction of the Commune and beyond. Constrained by what can be shown in an exhibition, CHARLES MARVILLE: PHOTOGRAPHER OF PARIS (National Gallery of Art, $60) distills Marville’s three-decade career into just 102 plates (plus essay figures), a small fraction of his output. Reproduced from tritone separations by Robert Hennessey, the images bring to life nineteenth-century Paris with such vividness that in one standout shot, the grain of wood on the side of a shed—perhaps a hundred feet from the camera—is seen in startling detail.

Ted Spagna’s “Sleep Portraits,” taken between 1975 and 1988, and collected in SLEEP (Rizzoli, $55), are typically a series of twenty to forty photos featuring individuals or couples (and sometimes more) in a bed, taken at fifteen-minute intervals during the night from a viewpoint directly overhead. Spagna had created a substantial body of work by the time he died in 1989 at age forty-five, from AIDS-related lymphoma. Edited smartly by Ron Eldridge and Delia Bonfilio, who also designed the book, Sleep is made up of grids that impose order and generate the illusion of narrative, to which we cheerfully succumb, as Spagna’s unselfconscious subjects—from infants to the elderly, restless singles to copulating couples—dance dream ballets across the page.

A single continuous panorama, eight inches tall and twenty-four feet long, Joe Sacco’s THE GREAT WAR: JULY 1, 1916: THE FIRST DAY OF THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME (Norton, $35) illustrates, in minutely detailed black-and-white drawings, events just before and during a summer day when the British army suffered more than fifty-seven thousand dead and wounded, its greatest single-day loss. A journalist known for comic books on contemporary conflict, such as Safe Area Gorazde, about the 1990s Bosnian war, Sacco conveys an eloquent, convincing, entirely wordless story. A sturdy hardcover slipcase houses the accordion-fold drawing and an accompanying booklet with an affecting, brief account of the day by Adam Hochschild.

WALL: ISRAELI AND PALESTINIAN LANDSCAPE, 2008–2012 (Aperture, $60) is Josef Koudelka’s book of purposely ugly photos—from which we cannot turn away. His expansive, brooding black-and-white panoramas have a paradoxical effect: Rather than expand our field of vision they close us in, evoking the experience of closed-off lands and claustrophobic, walled-in streets. The images show not only the familiar eight-meter-tall concrete slabs of what Israel’s government calls the “security fence” and Palestinians refer to as the “apartheid wall,” but also barbed wire, gates, cages, observation towers, and all the other machinery of segregation. The wall is a moral fissure in the landscape, dividing the haves from the have-nots, the putatively free from the certainly suppressed, and excluding all from extensive areas of military-only activity. Among many strange images is one of an empty town constructed by the Israeli army to replicate Palestinian population centers, for practicing urban warfare. They named it Detroit.

The challenge of a filmmaker monograph is to overcome the deadening effect of overenlarged film stills, staged production shots, self-regarding interviews, and (worst of all) academic film writing. THE WES ANDERSON COLLECTION (Abrams, $40) avoids all of these pitfalls in a survey of seven of Anderson’s features. Max Dalton’s charming children’s book–style illustrations introduce each film with a double-page spread of the movie’s principal location, incorporating “fourth wall” views suggested by Anderson’s familiar cutaway-dollhouse technique, used so well in the opening of Moonrise Kingdom and The Life Aquatic. Designer Martin Venezky unpacks the filmmaker’s sources and style—with an inspired deployment of stills, amusingly corny display type, and inventive layouts with images made to resemble postage stamps, scrapbook clippings, and other collectibles—perfectly capturing Anderson’s seductively twee combination of obsessive detail and ironic distance.

Lacking basic editorial cues, like subheadings and picture captions, RAYMOND PETTIBON (Rizzoli, $150) seems a smorgasbord of 325-odd drawings, though, actually, it amply surveys the artist’s work. After fifty drawings from the late ’70s through the mid-’80s, like his noirish film stills, it opens into brief thematic groupings—on art making, money, politics, religion, and male identity. Highlights include the artist’s perverse personae, such as a sex-obsessed Batman, a heroic Lone Surfer, the 1950s TV cartoon character Vavoom, and Gumby. Marred by a lack of attention to the relative scale of the juxtaposed drawings (as well as some soft reproductions from inadequate old photography), the book’s plates improve as it reaches the more recent complex, colorful, collage-like works on paper. Robert Storr’s essay on spleen and rage and a revealing interview with the artist by his LA confrere Mike Kelley provide the critical coordinates.

RAYMOND PETTIBON: HERE’S YOUR IRONY BACK, POLITICAL WORKS 1975–2013 (Hatje Cantz, $60) is superior in its design and reproduction, on uncoated paper stock appropriate to the art, but is also unavoidably reductive. A glance at the dates of Pettibon’s notionally topical drawings shows that his targets are often long past their sell-by dates as subjects for satire—like his early-’80s works sending up hippies and Vietnam protesters. He has a larger goal: to create a commedia dell’America whose stock characters, such as the Artist (Krazy Kat), the Politician (Reagan), the Movie Queen (Joan Crawford), and the Villain (Manson), pitilessly reflect the broken culture that produced them.

Mike Kelley’s death in January 2012 altered the form of his long-planned European retrospective, now traveling in the United States, from thematic show to career survey. Designer Lorraine Wild, who worked closely with Kelley on his many publications, and the editors, including curator Eva Meyer-Hermann, have produced the excellent MIKE KELLEY (Stedelijk Museum/Prestel, $85) under what must have been difficult circumstances. For once in an exhibition catalogue, the artworks are presented before the essays, in a clean, chronological selection of projects and series, with concise descriptive texts. Even so, try starting at the end, with the interview Kelley gave for the book—his last, and a great introduction to the work of an artist whose fine critical intelligence informed a sprawling, anarchic, and subversively hilarious body of work.

Christopher Lyon is executive editor of the Monacelli Press.