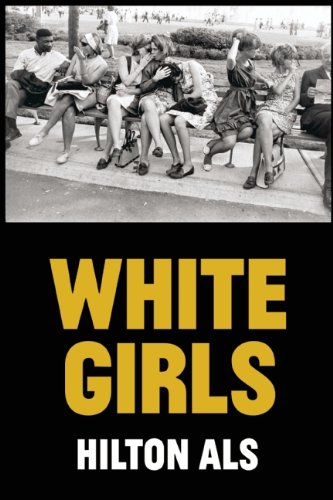

Hilton Als, a theater critic at the New Yorker for the past eleven years, knows how to make an entrance. The thirteen essays collected in White Girls—the long-awaited follow-up to his book The Women (1996)—all jump off spectacularly. His lead sentence for “White Noise,” on Eminem: “It’s outrageous, this white boy not a white boy, this nasal sounding harridan hurling words at Church and State backed by a 4/4 beat.” The opening lines from “You and What Army?,” told from the perspective of Richard Pryor’s older sister: “Some famous people get cancer. That’s a look.”

Yet even these audacious introductions aren’t as attention grabbing as the title of the volume itself, which is more provocative than that of its predecessor. The Women comprises three discrete meditations on individuals—including Als’s mother and those not born with double X chromosomes, such as the writer’s mentor and early lover Owen Dodson and Als himself—as they embody or reject the racially charged concept of “the Negress.” Despite that book’s gender discordance, its title sounds regal, imposing—a stateliness enhanced by the use of the definite article. White Girls, in contrast, suggests an epithet, a diminishment, a marker of privilege, a pariah status—us, them, nobody, everybody. Als’s always nimble, sometimes outrageous, complicating of alleged binaries—white or black, male or female, gay or straight—makes him one of our most vital, vibrant cultural critics. He continues to puncture pieties and received wisdom, dispensing piercing aperçus such as: “She was as conscious of her body as she was fearful of it; in short, she was a woman.”

Paradoxically, part of this volume’s strength is the elusiveness of its organizing principle. Als comes closest to pinning down what “white girls” means in the opening essay, “Tristes Tropiques,” the book’s most personal and, at eighty-four pages, longest piece. Reflecting on a thirty-year friendship—with a man called “SL,” for “Sir or Lady”—that has just ended, Als writes: “By the time we met we were anxious to share our black American maleness with another person who knew how flat and not descriptive those words were since it did not include how it had more than its share of Daisy Buchanan and Jordan Baker in it, women who passed their ‘white girlhood’ together.” If invoking Fitzgerald’s heroines calls up specific images of indolent Jazz Age conspirators, fifty-some pages later Als concedes the impossibility of ever defining the term: “No, she was a white girl, whatever that means,” he says of a dear friend, code-named “Mrs. Vreeland.”

Whatever that means: Only a writer and thinker as gifted as Als could transform what sounds like evasion or imprecision into expansion. Cut loose from meaning, “white girls,” for Als, becomes a springboard for mapping out an aesthetic theory, the term encompassing not only some of the women Richard Pryor, the subject of “A Pryor Love,” married but also the incendiary comedian himself. The seeming incongruity of that descriptor for the man infamous for a sketch called “Supernigger” dissolves as Als lays out Pryor’s “essentially American life, full of contradictions”—the complexities of an inimitable performer “who had an excess of both empathy and disdain for his audience, who exhausted himself in his search for love, who was a confusion of female and male, colored and white, and who acted out this internal drama onstage for our entertainment.” (“A Pryor Love” and other pieces here appeared earlier, in different form, in the New Yorker and other publications.)

The willingness to mine this “internal drama” is, according to Als, what made Eminem, né Marshall Mathers III, an artist; in contrast, Michael Jackson, who stopped looking inward after 1991’s Dangerous, is denounced as “the man who said no to life but yes to pop.” If the “work of the brilliant performer is to make a habit of disjunction,” as Als says in the Pryor essay, then Mathers’s most fundamental, most psychically violent act of disunion was detaching from his mom, Debbie Mathers-Briggs, a woman prone to “various psychological illnesses and heartbreaks” and only eighteen years older than her son: “Mathers’s inheritance was the Mrs. Mathers-Briggs show. He brought it with him when he left her to marry his audience. But he refined her hysteria, controlled it, gave it a linguistic form. By becoming an artist, he separated from Mother. He served her divorce papers by making records.”

For as cogent as Als’s analyses of luminaries are—whether of the stage, the page (Flannery O’Connor, Truman Capote), or fashion (André Leon Talley)—the writing itself stands as the most spectacular performance. “What is writing but an I insisting on its point of view,” he notes in “Tristes Tropiques”; Als’s genius is to make that first-person pronoun ever fluid. Consider the imperious declaration “I Am the Happiness of the World,” the title of an essay on Louise Brooks that showcases Als’s flair for ventriloquism. “I am Louise Brooks, whom no man will ever possess,” he writes more than once. Another incantation sets the rhythm for “Buddy Ebsen,” the curiously titled but more straightforwardly autobiographical essay: “It’s the queers who made me.”

“Speech is impertinent,” Als-as-Brooks announces, a quality that the writer singles out for high praise in many of his subjects, whether Talley’s “grandiloquence” or O’Connor’s “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” Nowhere does the author’s own penchant for exceeding and demolishing “proper” bounds play out more deliriously than in “You and What Army?,” the penultimate essay—or is it a short story?—in which the identity of “I,” Richard Pryor’s older sister, who may or may not be real, isn’t revealed until eleven pages in. This perhaps-apocryphal sibling, whose profession is doing “voice-overs for porn films,” dilates on, among others, her brother (whom she shrewdly describes as Gertrude Stein’s “bastard son”), Virginia Woolf, and the actress Diana Sands before shifting abruptly to recapitulate the miserable love story of two characters, presumably made-up, named Fran and Gary. In this destabilizing, exhilarating blur of fact and fiction, Als assumes the place of the performers he extols, making a habit of not only disjunction but also brilliant lunacy.

Melissa Anderson is a critic based in Brooklyn.