Carl Van Vechten was, by the late 1920s, “the nation’s unrivaled expert on the Negro, the man who had unveiled to the world the remarkable truth about the United States’ hidden artistic genius.” He was also one of New York City’s great narcissists. And he managed to distinguish himself even within this self-enamored group by carefully crafting his image for posterity—hoarding great stockpiles of material related to himself and feeding them to Yale and to the New York Public Library. So he is recognized as the connective tissue between Lincoln Kirstein and Gertrude Stein and Langston Hughes and the Fitzgeralds and H. L. Mencken and more because we have his photographs, letters, receipts, tax returns, report cards, and student essays. The Metropolitan Museum of Art even has his ties. That’s how it’s done, players.

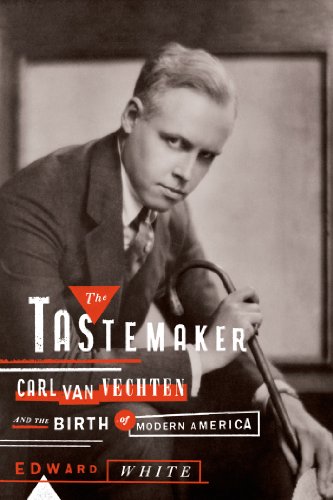

Van Vechten was also one of the Jazz Age’s most hedonistic, screaming, drunken homosexuals. (He was also married.) “Trying to sort people who lived a century ago into neat little piles of straight, gay, and bisexual by transposing their relationships to a post-Stonewall world is a difficult, and perhaps futile, exercise,” Edward White writes in The Tastemaker: Carl Van Vechten and the Birth of Modern America (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $30), but in most ways Van Vechten was gay as we understand it now—and certainly as his fellow tastemakers in Harlem understood it during the 1920s.

Van Vechten, of Cedar Rapids, did a few years at Hearst’s Chicago American, making up news stories, and then landed promptly, in 1906, at the New York Times. In 1913 he became the drama critic of the New York Press, and went to meet Gertrude Stein in Europe, where they saw Le sacre du printemps in its second performance, though he lied and said he was at the premiere. Back in America, he briefly edited something called The Trend, publishing Wallace Stevens, Mina Loy, and Djuna Barnes. His first book, released in 1915, was a work of criticism; in it, he explained that “music was on the precipice of revolution,” declaring that the future belonged to Stravinsky and Schönberg—and to black music.

The writing of Van Vechten on African Americans today reads . . . poorly. In 1920, he wrote an essay called “The Negro Theatre”:

How the darkies danced, sang, and cavorted. . . . Real nigger stuff, this, done with spontaneity and joy in the doing. . . . Nine out of ten of those delightful niggers, those inexhaustible Ethiopians, those husky lanky blacks, those bronze bucks and yellow girls would have liked to have danced and sung like that every night of their lives.

This ugly, exoticized racism was, alas, common fare in the New York of Van Vechten’s day, which was nowhere near so multiracial and polyglot as the metropolis is today. The number of blacks in the city more than doubled between 1920 and 1930, and even then New York City was more than 95 percent white.

Van Vechten made a name for himself as the city’s great white race interlocutor. He was the third author picked up by Knopf, right after Mencken. His second book was a runaway success, and he turned his influence toward the promotion of black artists. He was involved in staging Paul Robeson’s first concert at the Greenwich Village Theatre in 1925, wrote a series of articles on African American arts in Vanity Fair, got Langston Hughes published, helped organize the cabaret that began Josephine Baker’s career. All this hectic, and worthy, promotional work established him at the forefront of what Zora Neale Hurston called the “Negrotarians”—a loose group of well-off whites without whom “the Harlem Renaissance could not have happened,” White claims.

In 1926, when Van Vechten published Nigger Heaven—a novel about the “New Negro,” an idealized, educated, fun-loving, Harlem-residing class—he split his base in two. W. E. B. Du Bois was not a fan.

Van Vechten was also pathologically apolitical. (The “first and last . . . overtly political act of his life” was establishing massive archives of black—and self-mythologizing—material at Yale and Fisk.) Van Vechten instead “clung to the idea that . . . the world could be revolutionized one elegant cocktail party at a time.”

In August of 1927, Gertrude Stein wrote to Van Vechten:

What are you doing, I know why you like niggers so much . . . Robeson and I had a long talk about it it is not because they are primitive but because they have a narrow but a very long civilisation behind them. They have alright, their sophistication is complete and so beautifully finished and it is the only one that can resist the United States of America.

Stein’s observation, cloaked as it is in her own unthinking racist assumptions, nevertheless puts Van Vechten’s devotion to black people in a much better light. Emily Bernard, a professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Vermont, has written two books on Van Vechten. The Baltimore Sun asked her last year about how she reconciled his high-handedness, his privilege, and the gusto with which he believed in an essential black character. “It’s just such a relief to read and write about a person who wasn’t afraid to talk about race out loud,” she replied. That’s one thing that hasn’t changed much.

Choire Sicha is the author of Very Recent History (Harper, 2013).