In 1995, an emigrant from Germany who had lived almost thirty years in England published The Rings of Saturn: An English Pilgrimage, which uses a walk through East Anglia, on and near the coast, to gather reflections on time, destruction, connection, and culture. It appeared in English in 1998, without its subtitle; his next book, the essay collection A Place in the Country (1998), is only now appearing in English, about which more below; his next novel, Austerlitz, turned out to be the last book he would finish before his death in a car crash in December 2001. It takes just one awful second, I often think, and an entire epoch passes, he writes in The Rings of Saturn.

Reading these novels and his first to be translated into English, The Emigrants, was a high point in many people’s cultural life. If you’re someone who hears the tones of W. G. Sebald’s voice at all, it is hard to keep from coming hopelessly under its sway. His quivering sensitivity and thoughtful melancholy seemed to express, like nothing else, what life at the end of the twentieth century meant for anyone aware of the holocausts underlying the various triumphalisms one was expected to get on board with. Not everyone can eagerly turn their face away from the devastating past and toward the super-duper future, and for those of us who couldn’t, Sebald offered irresistible arias of historical aftermath. (A math is a mowing, so aftermath encodes a specific image, which Sebald used, of sheaves laid low, scythed down in the field. It used to be a positive word, referring to a second harvest the same season—not anymore.)

When we read Sebald fifteen or so years ago, his combination of historical acknowledgment and cultural engagement seemed definitive, but rereading him recently, I was surprised to feel the work out of date in some ways. I thought he had captured what it meant to be alive in our time, but our time has moved on: to put it bluntly, gone online. His method was one of drawing connections—“Since then I have slowly learned to grasp how everything is connected across space and time,” he remarks in A Place in the Country—but that is not something one learns slowly anymore. Here in Internet world, finding connections is the work of a nanosecond. The last two pages of Rings of Saturn catalogue various occurrences on the day Sebald finished writing, and it used to read as a deeply moving web of connections across time, moving because it tracked Sebald’s mind making those connections. Now it almost seems like a second-rate Wikipedia entry, /April-13-Events.

On the other hand, Sebald never just found connections or followed links; he made them, made them new. Sebald’s work is not encyclopedic, because it lacks any drive for totality or pretense of completeness—he follows whim, goes wherever things take him. In an interview, Sebald described his process this way:

It’s a form of unsystematic searching. . . . One thing takes you to another, and you make something out of these haphazardly assembled materials. And, as they have been assembled in this random fashion, you have to strain your imagination in order to create a connection between the two things. If you look for things that are like the things that you have looked for before, then, obviously, they’ll connect up. But they’ll only connect up in an obvious sort of way, which actually isn’t, in terms of writing something new, very productive.

The poet and translator Anne Carson once said something similar: “The things you think of to link are not in your own control. It’s just who you are, bumping into the world. But how you link them is what shows the nature of your mind.” Unsystematic searching, idiosyncratic linking: These are valuable as ever but harder to get to now, swamped as they are by the other kind. To the challenge of making imaginative connections has been added the challenge of making them visibly our own, off the preprogrammed, data-mined, hyperlinked grid.

Sebald speaks most directly to this aspect of our present moment in A Place in the Country, the collection only now translated after an unnecessary fifteen-year delay that may yet turn out for the best. Sebald’s English-language readers could certainly be forgiven for thinking we’d reached the bottom of the barrel after the slight Unrecounted (2004) and disappointing Campo Santo (2005), and A Place in the Country seems unpromising, with five essays on five authors and a sixth on the visual artist Jan Peter Tripp. Sadly, the English edition encourages this misconception, adding a dreary introduction, informative but unnecessary notes, and pedantically retained words and phrases in German throughout. A Place in the Country didn’t need this academic treatment any more than Rings of Saturn and Sebald’s other novels; thank goodness they were left to breathe as the living works of art they are. I hope that English-only readers will be able to see, beneath the clutter, that A Place in the Country is Sebald at his best, complete with the unmistakable photographs, the unmistakable tone.

As a critic as well as a novelist, Sebald is exemplary at showing the past at work in the present. He still remembers exactly, the book begins, how he put Gottfried Keller’s Green Henry, Johann Peter Hebel’s Treasure Chest of the Rhineland Family Friend, and a copy half fallen to pieces of Robert Walser’s Jakob von Gunten into his suitcase when leaving for England in 1966, and the untold thousands of pages he has read since then, he says, have done nothing to change his esteem for these books and their authors: “If today I were obliged to move again to another island, I am sure they would once again find a place in my luggage.” An almanac “even today constitutes for me a system in which, as once in my childhood, I would still like to imagine that everything is arranged for the best. . . . Nowhere do I find the idea of a world in perfect equilibrium more vividly expressed than in what Hebel writes about the cultivation of fruit trees [or] the different kinds of rain.”

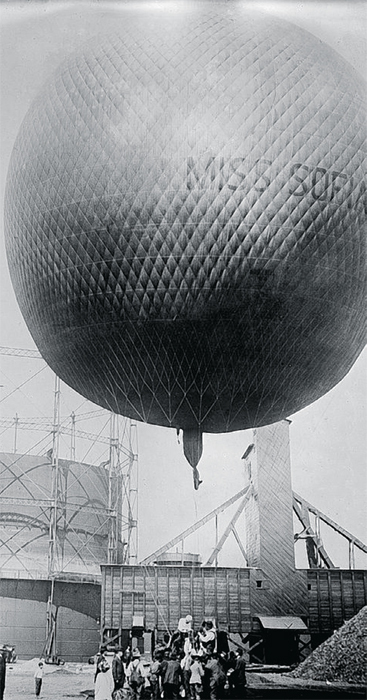

These essays restlessly explore how to find an outside view on an overwhelming world. Hebel’s “sovereign serenity” ultimately derives from his ability to see the world from a “cosmic perspective,” as though from a distant star. The Walser essay ends with a balloon trip: In all his prose, Sebald says, Walser wanted “to float away softly and silently into a higher, freer realm.” After paraphrasing a Keller description of junk in a warehouse, where here an ornate clock, there a waxen angel lead their quiet afterlife (ein stilles Nachleben; in Jo Catling’s fussier translation: “a quiet and as it may be posthumous existence”), Sebald goes on: “In contrast to the continuous circulation of capital, these evanescent objects have been withdrawn from currency, having long since served their time as traded goods, and have, in some sense, entered eternity.” This room of beautiful undead things has grave importance, laid out in the first sentence of the essay: “In no other literary work of the nineteenth century can the developments that have determined our lives even down to the present day be traced as clearly as in that of Gottfried Keller.” The worlds of these writers are also Sebald’s world, and still our own: defined by modern industrial capitalism and large-scale war. Napoleon comes up in every chapter, the guiding spirit of Place in the Country, as Nabokov was in The Emigrants; Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the book’s one pre-Napoleonic writer, is the object of Sebald’s greatest nostalgia.

Sebald also identifies with his subjects in more personal, less historical ways. He obviously shares their compulsion to keep writing—one hardly wants to help such sufferers, he admits of them and himself, “for the hapless writers trapped in their web of words sometimes succeed in opening up vistas of such beauty and intensity as life itself is scarcely able to provide.” The essay on German Romantic poet Eduard Mörike has more about erotic life, and suggests more about Sebald’s, than anything else he has written; the Walser essay is also about Sebald’s grandfather, who died on the eve of Walser’s last birthday. Every last thing in the book is about Sebald, thanks to the inimitable connections he forges, the resonance he always finds between his authors and his own lived experience. He is Walser’s balloonist, Keller’s clock and angel. A Place in the Country is an extraordinarily intimate glimpse over his shoulder, as close as we will come to a Sebald memoir.

The emotional peak comes when, decades after first seeing it, Sebald finally visits the island of political and spiritual refuge where Rousseau spent two months in 1765. Sebald doesn’t know why St. Peter’s Island means so much to him, but it does—Rousseau, for his part, called his sojourn there the happiest time of his life. Sebald stays for days, even though enthusiasm for Rousseau has declined “in the course of our own century, now nearing its end,” as evidenced by the few, mostly distracted visitors to the Rousseau museum there.

In our own, new century, of course, you can just google the place. How would the island have mattered differently to Sebald if he had done this, or had had to make the choice not to? What does place mean at all in the age of Google Earth? Sebald never addressed that question directly, but these essays suggest one key truth about finding our own answers: You have to go there. There is a website that maps the locations of the Rings of Saturn walk with those little upside-down teardrops, indexes passages from the book on the side of the page, and draws artificially straight lines to every other mentioned or referenced place. It is interesting enough, but nothing, nothing is further from the experience of reading The Rings of Saturn, or from Sebald’s own meanders, than scrolling around, zooming and clicking, to view that map and sidebars with snippets of text out of context on your little screen.

Even now, there are, Sebald reminds us, works of true connection, books like islands of refuge—a place in the country—that help you live in this world and outside it, too. This new and final collection of his nonacademic work, fifteen years late through no fault of its own, shows us more than any of his other books how Sebald succeeded in finding a place and passing over into eternity.

Damion Searls is a writer and translator, currently writing a history of the Rorschach test and biography of its creator, Hermann Rorschach.