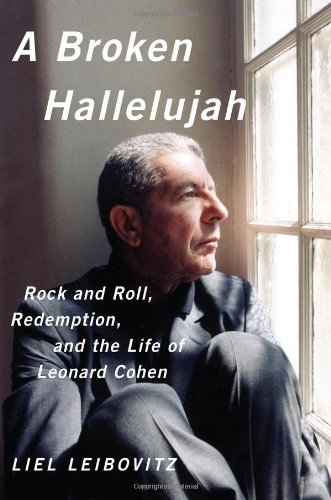

“So what is the prophet Cohen telling us? And why do we listen so intently?” Liel Leibovitz asks at the outset of A Broken Hallelujah, his moving portrait of the songwriter and poet Leonard Cohen. The author pursues the answers to these questions with the diligence and reverence of a religious scholar. Thank God. But Leibovitz recognizes that Cohen deserves more than mere rock biography, and so he structures A Broken Hallelujah around the premise that his subject is, indeed, a modern-day prophet.

Leibovitz’s account abounds with proof of this assertion, even as it charts the many other personae that Cohen has assumed through his long life and distinguished career. Still, to grasp the man’s peculiar sense of spiritual mission, one really need look no further than the greatest hymn of the rock ’n’ roll era, Cohen’s “Hallelujah”; in its closing verse, the singer proclaims, “I’ve told the truth, I didn’t come to fool you / And even though it all went wrong / I’ll stand before the Lord of Song / With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah.”

Leonard Cohen grew up in a wealthy Jewish family in Montreal. When he was nine years old, his father, Nathan Cohen, died from lingering injuries sustained in World War I. Young Leonard was left with his sister and mother, as well as an extended family that included his maternal grandfather, a fiery rabbi named Solomon Klinitsky-Klein, “a celebrated scholar who was known as Sar haDikdook, or the Prince of Grammarians.” After his daughter had married into the Cohen family, the elder cleric brought into their “increasingly assimilated lives . . . a core of traditional values and beliefs,” Leibovitz writes. Klinitsky-Klein impressed upon his grandson a “vision of Judaism radically different from the polite theology on offer at the Cohens’ Conservative synagogue; its language of punishment and justice, of damnation and salvation, was not the sort that the gentlemen in the top hats spoke fluently.” The language of his grandfather’s sermons gripped the young Cohen—particularly in its vivid depictions of how closely the sacred and the profane can interact.

The latter quality, by Cohen’s own account, animated his first foray into the writing life, as an aspiring poet. As he explained in a 1970 interview, “I wrote notes to women so as to have them. They began to show them around and soon people started calling it poetry. When it didn’t work with women, I appealed to God.” His poetry soon earned him wide praise in Canada, and, as Leibovitz explains, Cohen fell easily into the role of the capital-P Poet, “skillfully walking the line between genuine artist and smirking con man.”

Cohen was increasingly absent from his homeland, preferring to spend his time at the beachside home he’d bought on the Greek island of Hydra. There, uninterrupted by celebrity or family, he wrote. The poems gave way to longer fiction. His debut novel, The Favorite Game, published in 1963, was received warmly by critics. Three years later, his second attempt, Beautiful Losers, inspired some favorable comparisons to James Joyce but was mostly panned. Several reviewers decried the book as “filth”—and for the record, it did feature passages such as “Her freakish nipples make me want to tear up my desk when I remember them, which I do at this very instant, miserable paper memory while my cock soars hopelessly into her mangled coffin, and my arms wave my duties away.”

By the age of thirty-two, Cohen was ready to “abandon his modestly successful career as a writer and a poet.” What he chose to do next was typically unexpected: He moved to New York City to become a singer. An account of a dinner party at the beginning of 1966 serves to explain what might have contributed to the decision. A “cohesive group of poets” gathered in Montreal; at one point, when the writers were all well in their cups, Cohen asked the group, “Do you know who the greatest poet in America is?” He proceeded to play them two Bob Dylan albums. Cohen’s peers “loathed” the music—but for him, it had obviously struck a prophetic chord. By the end of that same year, he had succeeded in landing two songs on Judy Collins’s album In My Life—one of them his first signature hit, “Suzanne.” The record went gold almost immediately.

Cohen convinced A&R guru John Hammond to give him a shot on Columbia Records. In the late summer of 1967, a “nervous young artist” entered Columbia’s studios to record his self-titled debut album. It was a critical success, but Cohen’s popular appeal would be a long time coming: The music scene that greeted the release of Cohen’s debut was none too receptive to his austere and haunting balladry. “By 1969 Americans didn’t want redemption negotiated somberly to the tune of a lonely guitar,” Leibovitz writes. “They wanted it to come in bursts of sound, immediate, orgasmic.”

Cohen found his first significant following in Europe. Though he’d never been fond of live performance and had never been on a proper tour, his management and record label finally persuaded him to embark on a string of European concert dates in May 1970. He convinced famed producer Bob Johnston to be his tour manager and keyboard player. The tour got off to a bad start and never quite recovered. At the second show, in Hamburg, for instance, Cohen began goose-stepping onstage and sparked a near riot. “Cohen’s entourage, feeling more like a military unit than a band of touring musicians, became known as the Army.” Cohen, the Army’s commander, led them from one uncomfortable scene to another. It seems fitting that he had the idea to wrap up the tour with a gig in a mental institution just south of London. By all accounts, that show was the best of the tour. At its end, Cohen announced to the inmates, “I really wanted to say that this is the audience that we’ve been looking for. I’ve never felt so good playing before people before.”

A 1972 tour proceeded even more disastrously, thanks in large part to a poor sound system. With ’70s pop music slouching druggily toward prog rock and bloated excess, Cohen’s stark minimalism must have never seemed starker. Cohen again went into expat mode; in 1973, he traveled to Israel, where the Yom Kippur War had broken out. He found himself a part of a small group of musicians moving across the front line, playing for handfuls of soldiers between bouts of cannon fire.

The experience refreshed Cohen. The following year, he told a journalist, “War is wonderful. They’ll never stamp it out. It’s one of the few times people can act their best. It’s so economical in terms of gesture and motion, every single gesture is precise, every effort is at its maximum. Nobody goofs off. Everybody is responsible for his brother. The sense of community and kinship and brotherhood, devotion. There are opportunities to feel things that you simply cannot feel in modern city life. Very impressive.”

As the ’70s wore on, the “poet of loneliness” found himself very alone in his early forties, wandering from city to city. This state of geographic pilgrimage flowed, like many phases of Cohen’s life, into a spiritual quest. He became drawn to Buddhist meditation, and began to practice the Rinzai tradition. The merger of Cohen’s prophetic Jewish faith with contemplative Buddhist devotion was an improvisation of sorts, but as Leibovitz notes, it came naturally to Cohen: “Like God, the pious must learn to be in loneliness while striving all the while to create the world around them.” Cohen would spend much of the next two decades on top of Mount Baldy in Southern California, living in the monastery of an old monk named Roshi. When he emerged in the midst of his informal exile in 1984 with Various Positions, the album revealed a different, more intensely spiritual side of the artist.

It was fitting that Bob Dylan, who’d helped inspire Cohen’s musical career, recognized the album’s deeper religious ardor; the new songs, Dylan noted, “sounded like prayers.” This was especially the case for what is now Cohen’s most celebrated composition, “Hallelujah,” a song not so much about cosmic divinity as it is about the humility bound up with the ritual invocation of the divine. As Leibovitz explains of the song’s narrator, “He couldn’t feel, so he wrote a song, understanding that the Holy Ghost may preside over the occasional copulation, but that if humans were ever to meet their maker—the Lord of Song—the way to do it was through ritual, imperfect and frequently devoid of emotion but ultimately and cosmically effective.”

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, the culture caught up with Leonard Cohen. Suddenly, the former outcast poet, who’d been drowned out by much of the Dionysian din of ’60s rock, was celebrated as a hero—to Bono, Jeff Buckley, the Pixies, R.E.M., and everyone else who knew what it meant to be cool. By Leibovitz’s account, he enjoyed the new acclaim—to an extent. He found himself attending the Oscars, engaged to movie star Rebecca De Mornay, shooting music videos, feted and beloved. He went on lengthy (by his standards) tours in 1988 and 1993. Still, Leibovitz notes, the new renown was also “exhausting. Cohen drank. For reasons known only to them, he and De Mornay ended their engagement.” He spent the next five years marching with the monks atop Mount Baldy. But he wasn’t done. He needed the work. Ten New Songs and Dear Heather were well received, the latter earning a beautiful tribute from the great Village Voice critic Robert Christgau in which he lovingly describes Cohen’s “No Voice.”

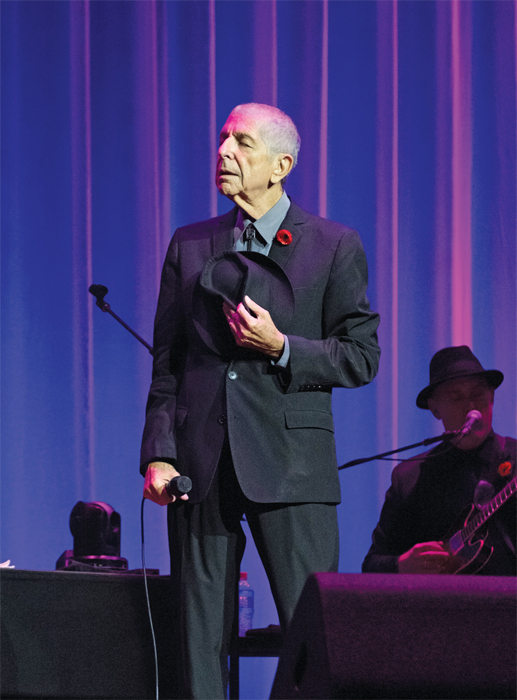

In the mid-2000s, Cohen discovered he had been rendered destitute by a former manager’s embezzlement. The only option he had to pull himself out of the hole was to tour. After two decades spent in and out of a monastery, Cohen was able to adopt a different approach to live performance. Cohen became a confident performer, killing it for three hours a night in front of sold-out houses, and playing a lifetime’s worth of songs for an adoring public. “The relationship was different now,” Leibovitz writes. “He had discovered an intimacy greater than the one he had grasped for as a young artist when he urged the audience to come closer. To bring them closer, he now knew, to be one with his fans, he just had to sing.”

A similar celebratory communion is achieved in A Broken Hallelujah. Leibovitz masterfully teases out the many powerful, and only provisionally resolved, spiritual longings that characterize Cohen’s work—no matter how profane its content may seem at first blush. Through all of the many reversals, switchbacks, and religious sabbaticals that have shaped his subject’s unique place in pop music, Leibovitz shows Cohen’s humanity shining through—while making it abundantly clear that he is first and foremost a prophet.

Rhett Miller is the lead singer of the band Old 97’s, which released its tenth album, Most Messed Up, in April. He is also a solo artist, and has written reviews and criticism for Salon and Bookforum.