At a time when the notion of a poetic career—with its requisite curriculum vitae, residencies, prize panels, and sabbaticals—has long been in ascendancy, it can seem almost quaint to recall that poverty or a sad demise was once a not-uncommon fate for a poet (think Keats, Rimbaud, Sylvia Plath, Dylan Thomas, Anne Sexton, Hart Crane). John Wieners met such an end in 2002, when he collapsed returning from a party in Beacon Hill, Boston. He was taken to Massachusetts General Hospital, where, lacking identification, he lay unconscious for days and then was removed from the respirator. Almost until the very end, his friends and family didn’t know he was there. Wieners—the author of several influential books of poetry, published journals, and plays—had, at sixty-eight, achieved a distinctive record of poetic work, political activism (he was a key figure in Boston’s gay-liberation movement in the early ’70s), and critical regard. But decades of drug and alcohol abuse, along with mental-health problems (he was institutionalized several times), had taken a hard toll, and this figure of undoubted importance to postwar American poetry was living hand-to-mouth in a walk-up apartment when he almost died as an anonymous John Doe.

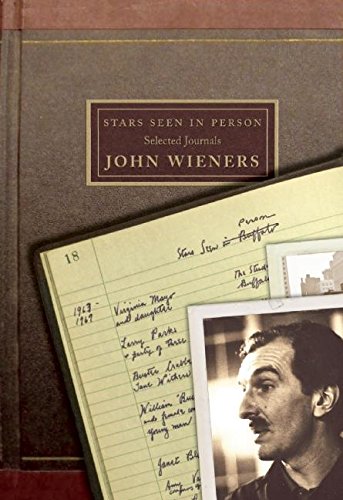

Certainly, Wieners’s struggles with substances and manic behavior didn’t pave a path to conventional success (tenure, prestigious awards), but the true impediment may have been his absolute fealty to poetry and a life of the mind that prized aesthetic experience over all else. Wieners was that rare poet who risked everything for the sake of his art. Just how high he placed the stakes is now made clear by the appearance of his earliest prose work, “The Untitled Journal of a Would-Be Poet,” in a new omnibus edition of four previously unpublished journals gathered by editor Michael Seth Stewart under the title Stars Seen in Person. In January, 1955, not long after turning twenty-one and graduating from Boston College, Wieners began keeping what he hoped would be a daily record of his developing sensibility. From the first pages the reader can’t help but be struck by the force of his enthusiasm for things literary (“I made the buying of that book a ritual as I nearly do with all the books I buy”) and his elevated sense of poetic destiny (“God tells me always to write and yet above this he is great mindbreak [new word, good] for his demanding from me of things I cannot give him”). The perceptions and revelations that crowd the pages are rendered with a cinematic acuity that heightens the diarist’s emotional intensity:

Tonight, I saw a beautiful grey-haired woman lying on a green bandana in the gutter of Tremont Street, waiting for an ambulance or death to carry her off to consolation. But the hope was there, another woman bent down as a song and fixed the bandana and seemed to stroke somehow the woman’s pain.

Wieners’s alertness to how metaphor might open the reader to the interior drama of the scene—the woman bends down “as a song” and strokes the pain—would soon be carried forward into his poetry. And, of course, this depiction of a life ebbing in the street among strangers also foreshadows the poet’s own lonely end.

But this youthful journal, which covers about a year, is hardly lugubrious. Great rushes of sentences recount dreams, ecstasies, debaucheries, and self-exhortations, often in immediate proximity: “I shall put the typewriter beside the bed again, and that shall strengthen me. This weekend was spent in Providence, amid martinis and Chartreuse liquor, and Seabreezes and Zinfandel, and homebrew beer, and parties.” Like most writers, especially in their early years, Wieners strives and fails to meet his own expectations. On a Tuesday in March, he announces a new morning work schedule; by Thursday, he is lamenting that “as might be expected” he has fallen off the plan, sleeping too late, dreaming of cockroaches “with green spotted wings.” Still, literary ambitions never cease to percolate: He discovers Charles Olson’s essay “Projective Verse,” meets the author himself at a reading in Boston, and by summer is studying at Black Mountain College, where Olson taught. Olson points him toward William Carlos Williams and Ezra Pound, and Wieners’s poetic education shifts into high gear as he studies these writers with growing fervor:

As I was reading Pound’s translation of “The River Merchant’s Wife: A Letter,” Marie became very upset, and the second time I read it, I could not go as we were crying so loud. It was beautiful in a cruel way to see her and Poetry the cause of it.

He goes on to say that he “would like to say so many things” but this journal “can never quite hold all the emotions and experiences I want to put down.” This awareness of language’s inadequacy—one almost all writers confront—seems to have troubled Wieners less oppressively. His often-quoted statement to his editor Raymond Foye—“I try to write the most embarrassing thing I can think of”—constitutes an expansive, even celebratory proposal and mode for literary creation.

The new volume contains three additional journals: The second, written in 1965 after Wieners had published what many consider his masterwork, The Hotel Wentley Poems, he dubbed with the jazz-flavored concoction “Blaauwildebeestefontein”; the third (“A House in the Woods—Moths at the Window”) and an untitled fourth were composed in the late ’60s. Most of the entries in these books are rendered in verse form, and the boundary between poem and diary notation is deliberately blurred. The exuberant naïveté that enlivened “Would-Be Poet” gives way after ten years to a more measured, sometimes despondent mood, as evidenced in this account of a visit to his family: “I came home to this house, feeling beautiful— / one week ago tonight, and now I do not / feel beautiful—these people have / crushed me—have crushed out the / beautiful.”

But “Blaauwildebeestefontein” also finds Wieners taking on the role of teacher. He champions his fellow Bostonian poets Stephen Jonas and Edward Marshall in a verse-inflected genealogy that cites them as bearers of a tradition that begins with Confucius and the troubadours and then moves into the work of Pound and Williams: “the vituperative / temper are here carried through to / an emotion of the highest / lyrical intensity.” Wieners, equally at home with popular culture and Renaissance lyrics, offers in the final volume the list poem “Stars Seen in Person,” a compilation of sightings and locales (“Lucille Ball / Saturday Matinee of the Star / Loew’s Teck / Buffalo New York”; “Dana Andrews / with bodyguards / 1963 8th Street / New York”) that strikes a comic note while remaining true to the devotional cast of the journals. This atmosphere of spiritual aspiration dates to the very first entry, one written after Wieners heard “a Jesuit priest called Leonard” read a poem of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s two days after her death. She became, the poet wrote, “a goddess to me from that instant on.”

This notion of the artist as a participant in some kind of sacramental exercise pervades Wieners’s verse, whose themes of abjection, rapture, sacrifice, and salvation mean that heroin, bulging cocks, and pleas to God mix freely together, all suffused with a profound sense of divine grace. This makes Supplication an apt title for the new selection of Wieners’s poems, edited by Joshua Beckman, CAConrad, and Robert Dewhurst, who include work from the author’s several books as well as from previously uncollected material. In “A poem for tea heads,” written in 1958, we begin with Jimmy the pusher, who teaches the poet “Ju Ju,” and we hear in slangy tones about buying marijuana and the likelihood of Jimmy’s imminent arrest and the poet being “placed on probation.” Wieners then pivots ever so subtly to transform the midnight streets to a metaphysical plane where the profane and the holy are ever in contestation:

The poem

does not lie to us. We lie under its

law, alive in the glamour of this hour

able to enter into the sacred places

of his dark people, who carry secrets

glassed in their eyes and hide words

under the roofs of their mouths

Another selection from The Hotel Wentley Poems, “A poem for cock suckers,” details the chiaroscuro world of mid-’50s gay bars in vivid, musical lines:

Well we can go

in the queer bars w/

our long hair reaching

down to the ground and

we can sing our songs

of love like the black mama

on the juke box after all

what have we got left.

Undemonstrative, present in syllables rather than grand thematic gestures, Wieners’s craft is evident in the simple yet tunefully assembled vocabulary—long, down, songs, love, box, got—that evokes the nightspot’s setting and mood. It is sighted in the delicate line break that facilitates the unpunctuated slide from “juke box after all” to the quasiquestion “what have we got left,” a move that draws on Olson’s method of employing lineation to complicate sense. The poem concludes with an emotional precision that ensures that images and diction with strong religious and sexual import align smoothly rather than collide:

It is all here between

the powdered legs & painted

eyes of the fairy

Friends who do not fail us

Mary in our hour of

despair. Take not

away from me the small fires

I burn in the memory of love.

Supplication offers a smart and eclectic introduction to Wieners. Alas, this review discusses but a fraction of its decades-long span, but it is possible to glimpse, even in the quoted portions of these two poems, as well as those from the journals, the extreme jaggedness of the psychological edge Wieners footed. The aspirations and proclamations of his journals and the emotional turmoil candidly recounted throughout the body of his work attest to a life lived in unembarrassed (and largely unremunerated) search of an ideal. And, as the volume’s title poem demonstrates, Wieners all too well knew the cost of that quest:

O poetry, visit this house often,

imbue my life with success,

leave me not alone,

give me a wife and home.

Take this curse off

of early death and drugs,

make me a friend among peers,

lend me love, and timeliness.

Return me to the men who teach

and above all, cure the

hurts of wanting the impossible

through this suspended vacuum.

This impossible isn’t an abstraction—it’s that less-scathed life forever outside Wieners’s grasp. There was no cure for the wanting, only the words to speak of it.

Albert Mobilio is an editor at Bookforum.