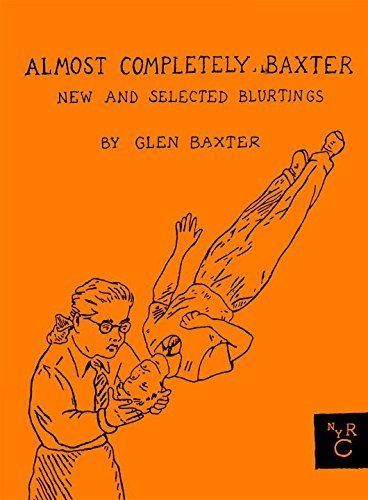

Opinion about the English sense of humor can prove a handy means of cleaving any social gathering into two mutually uncomprehending factions—those that think it exists and those that don’t. Despite the debate’s rather low stakes (this isn’t surveillance versus security), it is a revealing one personality-wise, and if you’ve ever labored to convince someone that Monty Python’s fish-slapping dance is funny, you know the gap in sensibilities isn’t trivial. Glen Baxter’s drawings, which have been collected in over twenty books since the late ’70s, amply evidence his native clime’s tradition of nonsense and just plain silliness—from Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear to P. G. Wodehouse and Benny Hill—and in doing so cause bafflement as easily as belly laughs. The very first cartoon in a new volume of Baxter’s work exemplifies the effect: Viewed from behind, three young men inspect the darkened entrance of a cave; if the kitchen utensils they wear on their heads are immediately apparent, the fluffy dog tails that sprout through the backsides of their pants are not. (Realized by the same quick dashes that articulate the folds on their suits, the tails are nearly camouflaged so we see them via a double take.) The text in most cartoons would at least hint at an explanation of the almost otherworldly scene, but here we have only a deadpan declaration: “It was precisely six-fifteen.”

Baxter’s comic realm—the space between image and text, between perplexity and the mundane—is a locale where uncertainty emerges as weird and weirdness recedes into uncertainty. The funny arrives as a slow-motion detonation that seems to dissipate as quickly as it boomed. This disquieting physics is surely the reason that Baxter has found a ready audience among the literati. In 1974, he gave a reading at St. Mark’s Church in the East Village “before an audience of poets, painters, and filmmakers,” he recounts in this volume’s introduction. “I stood at the lectern, dressed in a tweed suit, and began to speak. People burst into spontaneous laughter. I had arrived.” (The cheeky essay, though attributed to one Marlin Canasteen, a former “Security Advisor at the Bolick Mandolin Conservatory Society,” is clearly Baxter’s own.) Since that New York debut, his drawings, with their erudite nods to Dada and Surrealism, as well as allusions to mid-twentieth-century popular culture, have been regarded as a kind of visual poetry. Frequent comparisons to René Magritte and Edward Gorey aptly note the philosophical and satirical elements at play in Baxter’s humor; but his drollery is warmer, more gemütlich, owing to his affection for old movies (particularly Westerns and adventure flicks) and his apparent nostalgia for the hairstyles, clothes, and home decor of 1940s Britain. His world could be lifted whole from an Ealing Studios soundstage—pith helmets, sweater vests, fireplace mantels, and properly stodgy actors, too, all rendered in busy, typically colorless line work that deepens the vintage feel by evoking cartoons from that era. (Even Baxter’s nickname, Colonel Baxter, conjures an association with Colonel Blimp, the bloviating English military man in David Low’s satiric comics from the ’30s and ’40s.)

These staid and tweedy scenarios, however, are always upended by Baxter’s anarchic invention: In one of his rare color drawings, a distinguished gentleman, bald, with bow tie and cigar, sits with his tea setting by a picture window through which snow can be seen falling. As he reaches into his jacket pocket to retrieve, most likely, a pair of spectacles or a handkerchief, a chap in short pants, perhaps his nephew or protégé, plays the violin. The expression on each man’s face bespeaks nothing more than the comfy equanimity of a winter evening in a well-appointed home. The narration, though, has another tale in mind: “Slowly,” it reads, “but with unerring precision, Dr. Tuttle reached for his Luger.” The cozy image—the vacant yet kindly look on the older man’s face, his placid deportment in an ornate chair, the sprinkle of snow and almost audible violin notes—takes on an entirely new meaning when you read the text, which presents the sudden specter of not only a gun but a German World War II weapon. This, along with the imposition of “unerring precision” on the languid composition, is as shocking as it is ridiculous—like a blood-curdling scream uttered by a grown-up on the teacup ride. When governed by his sly caption, Baxter’s scene, familiar from any number of English films set in country homes, grows comically sinister: The doctor’s calm suddenly resembles a psychopath’s deliberation, while the younger man’s innocent focus on his instrument acquires the pathos of his imminent victimhood.

But not quite. The stock quality of the tableau and the carefully deployed language (is there a more harmless-sounding moniker than “Tuttle”? A grimmer lineage for a handgun?) announce their contrivance. The joke relies on our awareness of the artifice and a familiarity with its cultural references. (Monty Python’s Proust-summarizing contest isn’t a hoot unless you at least know that there’s a lot of Proust to summarize.) This is humor that is both knowing and nonsensical—laughter that depends on a savvy apprehension of details (the teapot, the short pants, Tuttle’s resemblance to Churchill) even as its mainspring is improbable, gruesome, and downright goofy.

Marcel Duchamp’s learnedly obscene subversions come to mind, and it’s no surprise that a young Baxter—attuned to the French artist’s comic seriousness—once wrote him in hope of obtaining a catalogue of his work. Baxter gleaned from Duchamp a sense of language’s malleability, the function of repurposing, and the power of the enigmatic. Indeed, in explicit homage to Duchamp’s kinetic works and readymades, Baxter invents and recombines objects: a cane with a lightbulb, giant teeth, a club-size pen attached to orthodontic headgear, and an assortment of implausible-looking machines imported, it seems, from Flash Gordon comics. Odd viewing contraptions proliferate. In one panel, a policeman has detained a motorcyclist and points an object—what could be a tiny telescope or flashlight inexplicably mounted on a display platform—toward the chest pocket he’s unbuttoning: “‘I’m afraid I’m going to have to show you my nipple, young lad,’ announced the constable gravely.” With its peephole, lamp, and spied-out nudity, Duchamp’s infamous Étant donnés is the unavoidable reference, one Baxter employs, it could be suggested, to shrewdly mock the prudish reaction that greeted the work when it was first displayed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1969.

This mischievous tack often tweaks the pieties of the art and literary worlds: Underneath the depiction of a man roped to a tree in a gloomy forest, we read, “Edgar had attended many a poetry evening.” A cowboy with gun drawn breaks up a fight: “‘We’ll have no alliteration in this here bunkhouse,’ snorted McCulloch.” Two children in bathrobes and carrying an old-fashioned lamp stumble on a family secret: “Daddy seemed to be running a lucrative little sideline churning out Mondrians.” And tagging Monty Python’s Proust routine, a pair of Western mountain men observe smoke signals in the distance: “‘It’s the second chapter of ‘“À la recherche du temps perdu” . . . ’ explained Big Jake.” While Baxter’s staged collisions of high, low, and middle usually work, they are sometimes less than pointed. At book length, they begin to feel perfunctory: His wit is best enjoyed not in extended sittings but rather, as is the case with much comic art, in small doses.

An ideal example of an image whose dire-to-daft transit makes for evergreen laughter presents a barren landscape marked by a few boulders, great tumbling clouds, and birds wheeling among them. At first we might mistake the two objects at the bottom of the panel for more rocks, but in fact they are the heads of men who have been gagged and buried up to their necks. The strong filial association with Samuel Beckett’s Nell and Nagg, who peak out from trash cans in Endgame, casts an existential spell on the scene, but the grim reality of such a torturous death isn’t negated by the literary ideation—it is a genuinely unnerving moment rather than a rejiggered outtake from Brief Encounters with parlor lamps and pocket squares. Or at least until you catch the caption: “The summer term was always a bitter disappointment.” Lickety-split, the viewer departs the desert, the circling carrion birds, the inevitable demise from heat and suffocation, to land in the faculty lounge, where tiny annoyances are regularly inflated into episodes of epic suffering. And there, between dying in the dust and cursing the copy machine, Glen Baxter finds his mark.

Albert Mobilio is an editor at Bookforum. His book of short fiction, Games and Stunts, will be published this summer.