It’s late 2009 and Jen, our heroine, has fallen on hard-ish times: She has been fired from her job as communications officer at a Madoff-scuttled family foundation, where she’s been cozily ignoring her true calling (art?) since graduating from college. When she gets bored of rattling around the cardboardy apartment that she shares with her public-schoolteacher husband, Jim, in an inadequately gentrified Brooklyn neighborhood they call Not Ditmas Park, she accepts an assignment from her college friend Pam to paint some portraits. She then allows her work to be incorporated, gratis, into an upcoming installation/performance by Pam, who is an authentic artist—i.e., one who lives with roommates in a filthy loft, etc. Just in time to prevent Jen from having to reconcile her dueling cravings for bourgie stability and creative fulfillment, another college friend intervenes with a job opportunity. Meg, who is a rich person, lines up an interview for Jen at a newly formed nonprofit that an ex-wife of one of Meg’s relatives is forming with her divorce settlement. “Would it be weird to be employed by a divorce settlement?” Meg asks Jen. “What’s actually weird is that I think last month Jim and I spent more money on cat food than people food,” she replies, breaking a self-imposed rule: Never talk to Meg about money.

Jen gets the job. This at first seems like a magnificent stroke of luck; Jen will not only be returned to her status as her household’s main breadwinner but will also, in working for an organization that seeks to empower women globally, be doing good in the world. Plus, she’ll be spending her days in thrilling proximity to a celebrity. Jen’s new boss is a charismatic cipher named Leora Infinitas, a woman who has transformed her own humble-origin story into a parable about willing yourself into material abundance; Jen’s new cubemate Daisy sums up her yoga-teacher-libertarian philosophy as “Zen Rand.” As Jen soon learns, Leora’s foundation, LIft, is one of those places that exist to fund-raise in ways that never require anyone to actually do anything besides talk about their plans.

From the opening pages of Break in Case of Emergency, Jessica Winter demonstrates a knack for rendering the surreal, almost trippy quality of being trapped in a Very Bad Meeting, the kind where time stops and everyone seems to be saying the opposite of what they mean. In the middle of the meeting that opens the book, Leora absently removes her eyelash extensions: “For one silent-screaming moment, it looked as if she were attempting to rip her own face off.” Later, a sycophantic staffer’s nodding is described as “slow-motion headbanging.” These descriptions establish Winter’s credibility; clearly, she has experienced enough similar situations to understand that satirizing them can be accomplished via reportage rather than hyperbole.

Jen is smart and ambitious and craves recognition; at LIft, though, she cannot help but try to find it in the wrong places, because all the places there are wrong. Though she doodles her way through the discussions of “this sensation of the year two thousand and nine leaping bravely into spring after such a bitter winter” and of focusing on “focus itself,” she still imagines that she’ll find meaning in an eventual personal audience with Leora. But Leora remains opaque; her dictates emerge garbled via the filter of Jen’s direct boss, Karina.

In Winter’s acute rendering, Karina is a manager whose persona will be immediately recognizable to those of us who’ve put in time at the kind of start-ups or vanity-project enterprises where there’s a lot of money floating around but not a lot of expertise, experience, or even real work to be done. She’s the type of boss whose supposedly benevolent motivations are in fact a cover for nasty, even sadistic behavior. Her faux-empowering lectures are actually thinly concealed bullying. “It’s not about blame,” Karina tells Jen, while blaming her for one of the many mistakes she has made herself. “You haven’t been here long and you’ve already made a big impact. I’m proud of you! I just wanted you to know that Leora, well, she just expects us to reach a little higher.” Karina has no idea what she’s doing and even less interest in managing Jen or Daisy. While Daisy wisely handles this situation by becoming an expert in looking busy while doing nothing, Jen continues to try. She can’t help it—she’s just the kind of person who tries. This makes her a terrible fit for her job; if she had Daisy’s knack for seeming but not being productive, she’d coast through her days unscathed. Instead, she keeps churning out pointless communiqués, sometimes relying on a prescription “cognitive enhancer” called Animexa to speed her through reams of recycling-bin-bound memos and briefs. She volunteers to flesh out the proposals “ideated” in those endless meetings—edu-preneurial summits and webinars designed around terrible acronyms like wise (Women Inspired for Self-Education) and well (Women Empowered to Love their Libido). Despite Jen’s obvious smarts, she simply can’t seem to adapt to the idea that doing anything is antithetical to LIft’s actual mission, which is to hemorrhage money as uselessly as possible. Fresh-cut flowers, “selected for their air-filtering qualities,” adorn LIft’s conference room daily; surely women in the developing world would be uplifted just to know their fates were being discussed in such rarefied air.

This mode of fruitless, self-sabotaging trying extends further than Jen’s nine-to-five life. Jen and Jim want to have a baby, but haven’t yet succeeded at doing so unaided, so they’ve been pursuing fertility treatments. These treatments force them to spend time and money in yet another realm of anxious striving and tortured acronyms; it’s a dark twin of the one Jen spends her workdays in. Paradoxically, the expense of the treatments is the No. 1 reason why she can’t just quit her terrible job. Ambivalence, or maybe just addiction, keeps Jen from participating in these efforts wholeheartedly; she’s been repeatedly told by the fertility doctors that she should lay off the Animexa if she hopes to get pregnant. But to keep her spirits and her output up at LIft, she needs the boost.

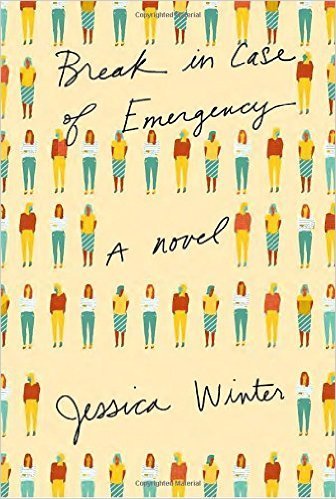

[[img:1]]

Though Winter’s book is billed as a satire, it barely contains any exaggeration, which can be mildly disorienting; sometimes it’s unclear whether we’re confronting a caricature or a portrait. Portraiture, of course, is Jen’s talent—she excels at reproducing photos as larger-than-life oil paintings, which all end up containing glimmers of her own eager-to-please personality, an “anxiety of obedience” that she knows she vibrates with at all times. “You are an astonishing technician,” a college professor tells Jen. It’s not hard to imagine someone saying the same thing to Winter, whose sharp perceptions and fluent prose are so much fun to experience that you might forget to wonder what her aim is in rendering the micro-details of this unpleasant, hollow-souled milieu.

But then, about halfway in, a series of crises cause Jen to reckon with some realer shit, and to come to terms with the fact that her approval-seeking isn’t serving any of her purposes. She is even forced to articulate her true desires to herself—ironically, via one of the self-improvement tools that her dumb workplace disseminates. Armed with a new sense of herself as a survivor with nothing to lose, Jen reexamines the relationships that have gotten her this far and finds a lot of what undergirds her life to be as flimsy as the walls of her apartment. She lashes out at poor Jim, who surprises her by lashing back. They both tell each other the un-take-backable truth, the kind that usually ends relationships: She bases her opinion of herself too much on external validation, and he doesn’t make enough money to be with someone like her—that is, someone who failed long ago to recognize that being around rich people all the time, living in a city full of them, would not inevitably lead to becoming one of them. “It’s all about money,” she tells him. “We can pretend like it’s not, but it is. Always. And it always will be.”

The fight continues, but changes location from deep Brooklyn to a party in Leora Infinitas’s penthouse, where Winter depicts a familiar scene: the private elevator, the deafening din, the gross smell of too much free cheese. Even among the party’s “gnarled gibberish waves of disorienting sound,” rich, graceful Meg “somehow located a sound frequency at which she could pitch her voice and be heard without shouting.” Jim is possessed of no such skill, and he embarrasses Jen by conspicuously shouting (and binge-eating cheese). It’s a small touch, but like Jen’s revelation, it’s achingly real. Some people—rich people, usually—do seem to have an innate talent for making themselves heard, while the rest of us have to embarrass ourselves by shouting.

More than a handful of recent novels, movies, and TV shows have succeeded in turning the low-hanging fruit of the contemporary office’s mockable folkways into delicious fruit salad. Winter’s book stands out, though, by making the stakes of Jen’s struggle to emerge triumphant from her stint at LIft so viscerally high. There’s often a degree of physical pain involved: Jen spends a lot of the second half of the book dry-heaving or being second-degree-sunburned on a careening ship during an island boondoggle of Karina’s (long story). Whether she’ll attain artistic success and quit her job isn’t a major source of tension; those portraits in the first act will obviously pay off in the third. Whether Jen and Jim’s Project will succeed, though—whether Jen can Have It All, and whether or not that would even constitute a happy ending—is a more nuanced problem, and Winter’s treatment of it elevates this book from an exercise in technical proficiency to something more bitter and toothy, something more like art.

Emily Gould is the author of the novel Friendship (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014) and the co-owner of the online feminist bookstore Emily Books.