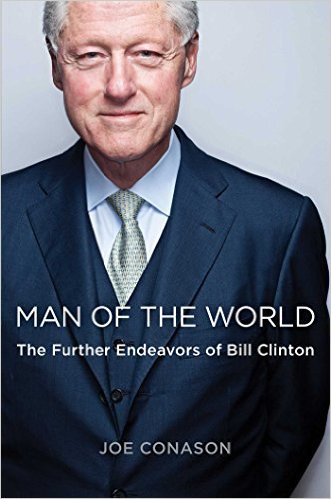

Few US presidents have done enough of any significance once they were out of office to rate books devoted to their post–White House careers. Nixon had Monica Crowley to play Boswell-that-ends-well, Jimmy Carter’s life and good works after 1981 will certainly deserve a fat tome or two, and I’d buy art critic Peter Schjeldahl’s (a guy can dream) George W. Bush: The Painter of Modern Life in an eyeblink. As usual, though, Bill Clinton is sui generis, comparable only to Teddy Roosevelt in his outsize presence and ongoing political impact sixteen years after his presidency. Hence Joe Conason’s nicely titled Man of the World: The Further Endeavors of Bill Clinton (Simon & Schuster, $30).

Choosing the dignified word “endeavors”—when even Bill’s honkin’ saxophone would agree “adventures” is more apt—is a candid enough advertisement that dirt isn’t Conason’s meat. He was an awfully hard-nosed investigative journalist in his Village Voice days in the ’70s and ’80s, not given to admiring any professional pol. (For the record, I worked for the same paper then, but knew him only by sight.) If he’s now a fervent Clintonista, chalk up another win for Bill’s legendary skill at beguiling people. Unlike, say, onetime Clinton basher turned Clinton haberdasher David Brock, Conason isn’t easily suborned.

Because he’s still a solid reporter, he builds a solid case for Clinton’s achievements since leaving office. Starting with the Clinton HIV/AIDS Initiative, which saved innumerable lives in Africa and elsewhere, some of them have been worthy indeed. Still, one could wish somebody had told Conason to put a sock in the special pleading that gives the game away.

The first major uh-oh comes just nineteen pages in, when—in the context of describing the fallout from Clinton’s notorious last-minute pardon of fugitive financier Marc Rich, no less—he rues how big Bill’s enemies went on attacking him once “he was no longer the leader of the free world but just another defenseless citizen.” Defenseless? Tell it to Trayvon Martin. As a fellow ex-Voice-nik, I also marvel at Conason using a cant phrase like “leader of the free world” unironically, not to mention sympathizing as he does with Clinton staffers’ fretfulness about protecting the boss’s “brand,” even when it was still a brand without a product.

So far as the Rich pardon goes, it turns out in Conason’s account that Bill was acting virtuously. He felt he owed Ehud Barak for going the extra mile to back Clinton’s failed Middle East peace deal, and Barak had filled him in that Rich had done Israel considerable service as a behind-the-scenes conduit to officially hostile Arab regimes. But the logic of this is both murky and flimsy, since the businessman’s sub rosa activities had only benefited Israel, not the United States. Besides, if Barak felt so strongly about it, couldn’t he have offered Rich asylum and taken the heat himself? Once Conason finds a way of putting Clinton in a good light, he doesn’t have a lot of appetite for delving into distracting ambiguities and ramifications, a pattern repeated throughout Man of the World.

With that imbroglio neutralized, the author can get on with his tale of Clinton the wonky, tireless do-gooder, bounding from AIDS-stricken Africa to tsunami-devastated Southeast Asia to hurricane-wrecked Haiti and generally behaving like the “one-man Peace Corps” that the world’s most effusive gadfly, Chris Matthews (another critic turned gush factory), once congratulated him for being. His genuine humanitarian zeal deserves admiration, and got it from, among others, George W. Bush—who went from obstructing Clinton’s AIDS project, which the White House saw as a noisome rival to Dubya’s own parallel program, to enlisting Bill to play dynamic duo along with George H. W. Bush in more than one disaster-relief campaign. But all the same, Conason’s relentlessly adulatory saga does feel a mite incomplete.

Early on, he stresses Bill and Hillary’s financial anxieties when they left the White House more than $11 million in debt, mostly in unpaid legal fees. But only a couple of hundred pages later do we learn what alleviated their short-term woes: Bill’s cushy gig as an “adviser” to the unlovely Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa Companies, which netted him $12 mil before he severed the connection during Hillary’s first White House run. By then, the couple was worth $109 million, a startling stash to accumulate in just eight years.

Needless to say, Burkle was hardly the only moneybags among the Clintons’ new BFFs. Man of the World has Bill borrowing so many gazillionaires’ private planes for his globe-trotting that it’s a “Fanfare for the Common Man” relief when he actually charters a flight somewhere. But Conason refuses to see any downside to all this chumminess, either in terms of its potential for corruption (debatable) or its psychological effect on both Clintons (fascinating to mull). It’s enough to give you a new appreciation for the fact that the Clinton Global Initiative’s initials are CGI.

He’s also damned if, even to refute it, he’ll bring up the rumor mill’s tittle-tattle about the perks of Bill’s life with the jet set. While Wall Street honcho Jeffrey Epstein’s name crops up once or twice, you won’t learn from Conason that his private plane—which Clinton reportedly flew aboard two dozen times or more—was nicknamed the “Lolita Express” for its alleged airborne corral of available teens. Even if our most famously randy POTUS since JFK didn’t, ahem, partake, his unconcern about associating with a sleazeball like Epstein, who wound up doing prison time for soliciting an underage prostitute, is remarkable.

So is Conason’s explanation of both Clintons’ fabled tone-deafness when it comes to setting off ethical alarm bells. “They felt so sure of their own probity and benign purposes,” he writes, that they weren’t—and presumably still aren’t—able to fathom how others might perceive their actions differently. Funnily enough, the identical formula applies to Man of the World’s author, who’s got too much confidence in his probity to recognize he comes off here as their shill.

Tom Carson is a freelance critic and the author of the novel Daisy Buchanan’s Daughter (Paycock, 2011).