Looking at someone you find attractive—better yet, someone you hope also finds you attractive—your gaze might brush the floor before your eyes meet; while you shift from foot to foot, your hand may sweep a lock of hair behind your ear. This feels artless, an outer expression of an inner flush. On closer inspection, it’s clear your movement is pantomime, not instinct. You have been choreographed—by a beautiful actress on the screen, or by, say, a friend’s older sister, whose beauty is all the more amazing for its proximity: How could such glamour be in your kitchen, leaning on your linoleum counter? You spend a lifetime trying to re-create it.

This same gesture, pushing back one’s hair, is quietly enclosed in Trisha Brown’s 1972 work Primary Accumulation. The choreography was a reversal of the above: Brown wanted the audience to be uncertain, to question whether the movement was part of the dance or a brief reprieve from it. When the gesture is multiplied by a quartet of supine dancers in Group Primary Accumulation, 1973, there is no doubt that it has been composed—careful turns of wrists, elbows, and hips repeat and accrete with mathematical precision. And yet the recumbent versions of this dance, executed on floors and grass, have something distinctly un-choreographic about them. As Brown wrote, “To lie down on your back is like quitting dancing.” The performers stretch and curl; their chests go convex with ecstatic pleasure, as if yanked by a thread. Desultory heaves and rolls become recognizable as dance only when repeated and done in unison.

The difficulties of seeing and making dance are at the core of Susan Rosenberg’s new scholarly monograph on Brown, one of the foremost postmodern choreographers. Examining the first twenty-five years of Brown’s career, Rosenberg’s rich compendium appears in the wake of a great loss; Brown died in March of this year. The book begins with her 1962 choreographic debut, Trillium, and ends with Newark (Niweweorce), 1987, a work in which Brown introduced a weighted, gymnastic vocabulary of movement and incorporated richly saturated backdrops designed by Donald Judd. In many ways a “new work” (for which the title is a wry homophone), it was also an ending, a dance in which Brown did not give herself a role. It’s appropriate that it concludes the book, though it was made less than a decade into Brown’s proscenium phase, when she moved her dances out of the gallery, museum, and street and onto traditional stages.

The seventeen years Brown spent working outside of conventional theater spaces were undeniably the crucible in which she forged her distinctive vision. While Rosenberg’s subtitle, Choreography as Visual Art, is nominally attuned to the ongoing—and seemingly endless—debates about dance in the art world, the book is not, in fact, primarily an argument for dance’s legitimacy in that context. Perhaps Rosenberg is as exhausted as I am by the ways this conversation, undoubtedly important, has too often elided a consideration of the slipperiness and specificity of dances themselves.

In what she calls an “antidote to generalization,” Rosenberg offers precise descriptions of Brown’s work. Each of the ten chapters examines a cluster of deeply intertwined choreographies, delving into the specifics of their creation. The book benefits from her role as “consulting historical scholar” at the Trisha Brown Dance Company: It’s rooted in rigorous archival research and takes advantage of Rosenberg’s proximity to oral histories, both formal and informal. While I resist the logic that assumes intimacy is less critical (i.e., valuable) than distance, readers should bear in mind the author’s association with Brown’s company. This embeddedness disguises the impressive scope of Rosenberg’s scholarly labor; the book gradually unwinds as if written from muscle memory—the deeply felt knowledge that makes choreography look natural.

Rosenberg details Trillium’s debut, giving the story of a jury first rejecting it, then relenting—a familiar origin tale for the avant-garde (think of Marcel Duchamp, Vaslav Nijinsky, or John Cage). Anticipating the pared-down grammar of Judson Dance Theater, of which Brown was a founding member, Trillium was a study in reduction, based on three tasks: “stand, sit, and lie down.” The dance’s namesake—a wild perennial found in Brown’s hometown of Aberdeen, Washington—is also a metaphor. The flower, with its trio of petals, resists domestication, as it will have withered by the time one gets it to the front door. Diving into these early works, Rosenberg approaches the provocation of her subtitle obliquely. Rather than focus on dance’s validity as art, she instead makes visual the contested term. Brown’s oeuvre is undeniably remarkable for its attention to physical space and optical perception. Yet Rosenberg instead emphasizes what she calls “reprisal as a choreographic motif” in Brown’s work—in other words, choreography’s inevitable wilt. While recent writing has wrestled with dance’s immediate disappearance from the minds of viewers and the role of technological documentation in capturing it, Rosenberg instead addresses how dance fades corporeally: Bodies are imperfect archives, and movement inevitably shifts as it is transmitted from its maker to other dancers, acclimating to their differing anatomies. In this telling, dance is not just hard to see, but also hard to do.

Thus, the visually spectacular “Equipment Dances,”1968–71, are also strenuous feats of bodily memory. In the famed Man Walking Down the Side of a Building, 1970, a dancer does just that, wowing audiences by struggling mightily against habituated proprioception in what Rosenberg calls “an effortful reconstruction” of everyday locomotion. In Roof Piece, 1971, dancers stationed on SoHo rooftops make semaphoric gestures, raising and outstretching their arms in various configurations. As the motions are conveyed across great expanses, their fidelity to the original necessarily deteriorates. Rosenberg reads this work as “a critique of choreography’s timeworn model of person-to-person transmission.” From one point of view, the movements are degraded and impure, but it’s also true that each performer adds elements specific to his or her own body; the effect can be read less as corrosion than alloying.

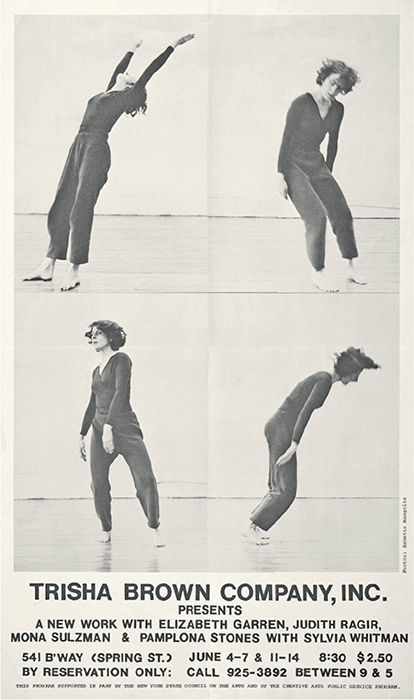

These explorations have long given Brown greatest purchase on the visual arts. The “Equipment Dances” track the art-world obsession with phenomenology, gravity, and process; likewise the “Accumulations” take on seriality, systems, and conceptual structure. Yet Rosenberg’s considerations of the plastic arts are tempered, the comparative examples brief. Instead, she carefully attends to Brown’s engagement with dancers—how she enfolded them in the making and unmaking of movement. One little-known riff on the “Accumulations” that was performed at the Sonnabend Gallery is exemplary: In theme and variations, 1973, one dancer performs “while a second one tries to foil her by twisting, turning, carrying, sitting on and talking to her,” Rosenberg explains. Will the dancer continue undaunted, or will she be distracted and lose her place?

It was at end of the ’70s that Brown moved to the proscenium, explicitly challenging the conventions of theatrical space. Glacial Decoy, 1979, is danced at the stage’s margins, tugging the viewer’s vision to the edge of the frame via a dizzying array of entrances and exits. Rosenberg shows how this stage work nonetheless continued Brown’s tireless dedication to her dancers’ somatic perspectives. In Glacial Decoy, as in the renowned Set and Reset, 1983 (both feature costumes and stage design by Robert Rauschenberg), the choreography is built on what Brown called “memorized improvisation.” These works were first composed by Brown, then transformed by the dancers’ personal variations. The resulting movements were then fixed in place with a hawk-like acuity, forever registering each “individual body’s imprint on her forms.” Rosenberg rightly locates Water Motor, 1978, a brief solo documented on film by Babette Mangolte, as the sea change. Inaugurating a new phase of Brown’s career, the dance demonstrated a newly sensuous approach full of witchy contortions and furibund exertion. Described by Brown as “representational movement to me, but . . . abstract to everyone else,” Water Motor also contains what she called “fugitive” personal imagery, “fetishistic little things.” This is one of the book’s glimmering threads: Rosenberg reveals that many of Brown’s dances transmuted a private memory by, in her evocative turn of phrase, “decanting it to vision.”

There is one hidden moment in Water Motor that is, to my mind, most revelatory—my personal fetish. Brown pauses to look at something or someone in the stage-right wings. This happens during a not-quite soutenu, a balletic half-turn that she stalls, making manifest its English translation, “sustained.” Hands at her chest and facing away from the camera, she tips back, surrendering, her feet catching. She advances toward the point she’s gazing at, then swerves. Carried by her own momentum, Brown moves on to a vertical reach, a discandied torso. I do not move on. I am caught there, in her hanging prepositional phrase, a movement that seems made for or addressed to—what or whom, I won’t ever know.

The contradictions of diffusion and specificity are everywhere in dance, but they are particularly intimate in Brown’s work. One anecdote best encapsulates how her legacy remakes the very idea of a dance company’s “house style,” slyly perverting the doctrine that makes a Balanchine-trained dancer instantly recognizable by her rounded hands and separated fingers. In Group Primary Accumulation, the dance with its furtive brush of hair behind the ears, there is another secret. Brown’s own peculiarly bent middle finger (the result of a childhood injury) has been unintentionally replicated by the dancers, made into choreography. What more could you want from dance than this: the idiosyncratic grammar of flesh ushered into the future, the result of tender, exalted looking.

Visit artforum.com to read Peter Eleey’s Passages tribute to Trisha Brown in the Summer issue.

Catherine Damman is an art historian and writer.