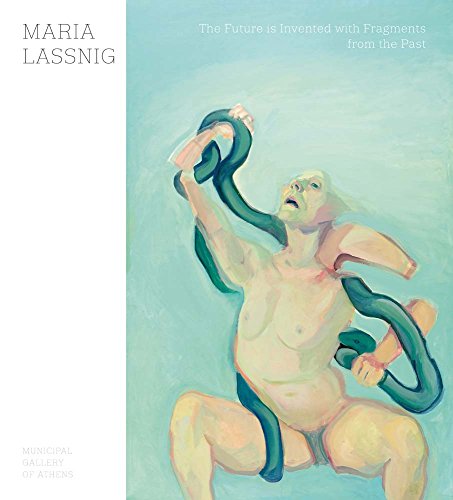

LAST SPRING, DOCUMENTA, the beleaguered quinquennial art exhibition, proposed a rethink of the notion of Europe, decamping to Greece for an attempt at “Learning from Athens,” as its title claimed. Amid the festivities was a show at the Municipal Gallery of Athens, more modest in scale but every bit as ambitious in scope: “Maria Lassnig: The Future Is Invented with Fragments from the Past.” One of the final projects the great Austrian painter developed before her death in 2014, the exhibition compiles sketches, watercolors, and paintings charting Lassnig’s infatuation with Greek mythology. Primarily self-portraits, the images capture the artist infiltrating the ancient tales, painting herself in the poses of Aphrodite, Atlas, Sisyphus, and any number of Nereids, caryatids, and Amazons.

This is more than just a divine drag act. By inserting herself into these myths, Lassnig casually upends their traditional interpretations. The first page of the show’s catalogue features a waggish 1980s-era pencil sketch of a naked woman bowed atop a bull, her thighs voraciously clamped against the animal’s haunches. This is not the Europa we’ve come to know, the soft sliver of a maiden gliding with her snow-white bull across one of Paolo Veronese’s canvases or the Greek two-euro coin. Lassnig’s 1994 watercolor Kretastier (Cretan Bull) twists the story even further, presenting the artist as a plum-nippled Europa rising from the cerulean shallows, a puny purple bull slung around her shoulders like a stole.

The catalogue supplements reproductions of these works with a suite of six essays in which writers indulge in their personal deifications of the artist. Curator Hans Ulrich Obrist appends to his introduction a poignant, unfinished letter sent to him by Lassnig. (Its inclusion here suggests a mythologizing of the recipient as well as the sender.) Amy Sillman picks up the motif of gods dwelling among men with a letter of her own. Addressed to Lassnig, the note speculates on the experiences they undoubtedly shared back when both painters lived blocks from each other in New York, though they never met. Daniela Hammer-Tugendhat slots Lassnig’s “Europa” paintings into a lineage of depictions of divine bovines and the maidens they carry, while Denys Zacharopoulos reads Lassnig’s “taking the bull by the horns” as a quintessentially feminist endeavor of self-assertion.

But the “self” Lassnig is asserting is a Zeus-like changeling, capable of enticing or alarming in equal measure. The painter’s raw power lies in her injection of a distinctly mortal frailty into her pantheon, imbuing her portraits with a plaintiveness shades deeper even than the blue Aegean.