The first thing that catches your eye about the London-based White Review’s third issue is the color gradient on the cover, which shades from a mesmerizing forest green to light burnt orange. After this, it's what's inside: The magazine features an impressive variety of work—from poetry and fiction translated from Japanese, Spanish, and Yiddish to reports on the extinction of whales in the Antarctic and stories of Perec and the Situationists in Belleville. In addition to producing a quarterly print publication, the White Review publishes monthly online issues and programs events in London and elsewhere. In honor of the release of the fourth issue, Bookforum interviewed founders and editors Benjamin Eastham and Jacques Testard about starting a magazine and the differences between New York and London's literary cultures.

Bookforum: How did the White Review get started? Did you begin the project to fill a hole in the literary world or to strike out toward something new?

White Review: In the winter of 2010, Ben was working at the Hannah Barry Gallery in London; I was interning at the Paris Review in New York and living an incredibly clichéd Williamsburg existence. We were friends from university in Dublin, so when Ben came over to NYC on art business, we spent the weekend together and ended up realizing that there was no multidisciplinary journal publishing short stories, interviews, and artwork in Britain. We decided there and then that we would be the (unqualified) ones to do it when I moved back to London a few months later.

Our reasoning stemmed in part from the fact that it is extremely difficult for young writers—and, to a lesser degree, artists—to have their work published in the UK, simply for lack of outlets. So, to answer both questions, we were attempting to fill a hole in the literary market by creating a serious quarterly arts-and-literary journal in London—something that didn’t exist—and we also wanted to do something new by bringing the different and often separate fields of art and literature together. Last but not least, we wanted to design the magazine to make it visually striking and desirable as an object—because that’s how we believe books will survive in the new media age.

Once we established the basic premise of what we wanted to publish—short stories, essays, poetry, reportage, interviews with prominent writers and artists, photography, and artwork—it took us about nine months to get the money together through crowd funding and donations for a first issue, and to design and produce that issue, which launched in February 2011.

BF: How do the literary worlds of New York and London compare? How much of a London publication is the White Review? Does it matter anymore where a publication or project is based?

WR: In lit-mag terms, the literary scene in New York is infinitely more happening than London’s. There are so many great magazines, many of which are youngish, that would have made the White Review almost pointless had they existed in London. We’re thinking of n+1, Guernica, Cabinet, the Paris Review, Bomb, Bookforum; In London, Granta is close to us only in that it publishes fiction and reportage, although they work with more established writers. The publications that dominate the scene—the two biggest being the Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books—have a narrower focus, as their names suggest.

As for the White Review’s status as a London publication, that’s a difficult question. Our geographical location is perhaps reflected most in our interviews with London novelists, such as Will Self and William Boyd, and artists, such as Paula Rego and Richard Wentworth. For now, we’re primarily being read in London, and we’ve found a local readership that didn’t necessarily know of the New York–based publications listed above. Also, we’re drawn to mainland Europe—particularly to Paris, where the original Revue blanche was founded in 1889, and to Berlin, where a lot has been happening in the art world in the last decade.

Location doesn’t really matter though, not anymore, certainly not in terms of content. If it did, we could never have hoped to publish the likes of Joshua Cohen or Diego Trelles Paz, nor would we have been able to put on an event at the Cabinet space in Brooklyn without either of us having set foot in the US for over two years now.

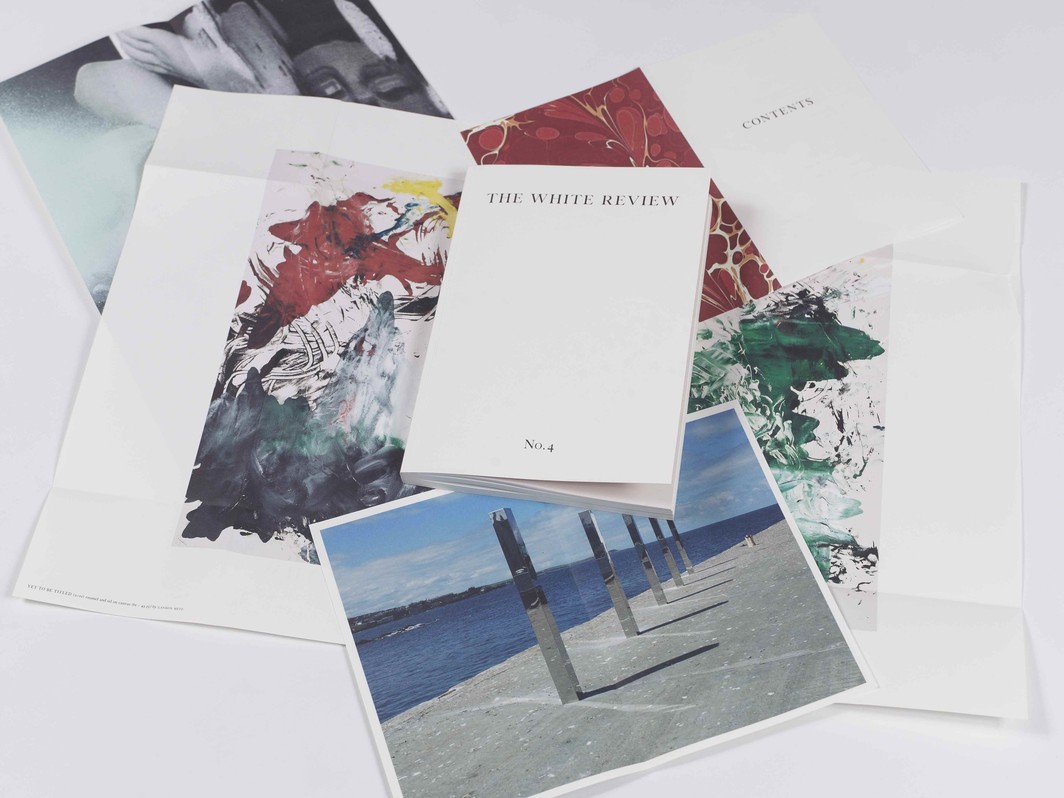

BF: The physical structure of the magazine is also unique—the additional cover, which folds into a poster, and the pullout table of contents. How do you conceive of the relation between the physical magazine and its contents? Your commitment to print entails a commitment to a physical object—do you think of going further, introducing other “nonmagazine” aspects?

WR: The relationship between the magazine's format and its contents relates to what we were saying earlier about the book as physical object. We value the content, therefore we value the way it is presented, and we value how the White Review is packaged and what the overall sensory experience of reading it is. The dust jacket was our art director Ray O’Meara’s idea, as were the other detachable bits and bobs—posters and other assorted inserts—that we include in each issue. The idea, again, is to experiment with the book form or even to push the boundaries of what that can include. We see the White Review as a collectible item—content apart—and its amorphous physical appearance is part of that vision.

Looking beyond the magazine, we’re thinking about publishing essays and novellas in paperback soon. Hardback anthologies with a curated selection of our best content for a given year or two have also been discussed, as have artists’ editions, with unique prints and nontraditional packaging. Making publications with a gallery has allowed us to look at different ways of presenting images and text—from collections of experimental writing to handmade boxes containing artists’ prints stitched together. We’d love to pursue these avenues with the White Review, given the time and money.

BF: More on print: Your magazine, especially issue 3, has an intense fungal musk to it. Where does the smell come from? Can you talk about your paper a bit?

WR: We had to draft Ray in to answer this one: “Offset printing is a complex craft and can be intoxicating in many ways. The smell you refer to is an amalgamation of soya-based vegetable ink and Olin uncoated paper, which comes from a mill just outside Paris. It’s interesting how that context—the tactility, the smell, the weight, the texture, and the typeface of a book—can become the lens through which we read the content. The scent of a book freshly printed and that of a book thirty or three hundred years old are very different things, and naturally that has an effect on the reader’s experience of it, not only in terms of the object, but also in their understanding of the actual text.”

We might add that opening a smelly book is one of those timeless, evocative experiences, one that anyone who likes books can relate to and will enjoy. And we like books too, so we’re delighted that the White Review has that “intense fungal musk,” as you call it.

BF: In general, English-speaking readers read very little in translation. You are clearly focused on attempting to remedy this or at least beginning to. How does translation figure into your overall project? Are you interested in specific regional or national literary cultures?

WR: Publishing fiction and poetry in translation is not so much an attempt to remedy the situation, as you say, but rather part of our project to publish writers unfamiliar to our audience. If these writers happen to be writing in other languages and we feel that they are worth reading, we include them. Translation, when done well, is fantastic. Janet Hendrickson’s work on Federico Falco’s “Fifteen Flowers,” for example, was superb, and he’s a writer we expect will go on to great things outside of the Latin American literary world.

As for specific regional or national literary cultures that we’re interested in, we’re naturally drawn to France because I [Jacques] am a native Parisian and still read in French a lot. As for specific non-English literature that is underrepresented, China is pretty high on the list, considering its growing economic and cultural significance worldwide. We’ve modestly tried to remedy that by publishing a very funny story by Wu Ang online, which attacks the misogynist values of the contemporary Chinese literary scene. Translations are hard to come by though, especially because we can’t pay for them. If you are a budding translator with some stories to place, get in touch.