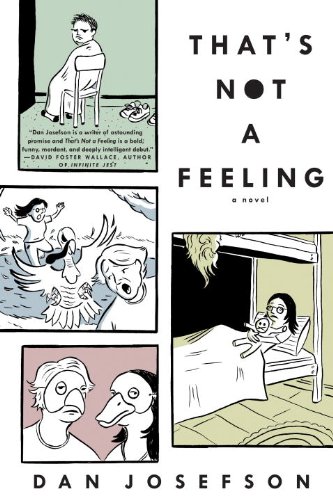

Perhaps the most confounding thing about this uneven novel is its prominent blurb from David Foster Wallace, who calls the book “a bold, funny, mordant, and deeply intelligent debut.” This might not be worth bringing up if That’s Not a Feeling wasn’t so clearly an attempted foray into Infinite Jest territory. Both novels are concerned, at least partially, with the tangled inner lives of young people; and both are interested in the ideas surrounding therapy, the misguided ideologies of institutions, and what it means to be unwell and to get better. Yet while Wallace wrote a book about a tennis academy, addiction and recovery, and Quebecois terrorism, Josefson has confined us to a much smaller and far less rewarding fictional world.

That’s Not a Feeling relays a few complicated months at Roaring Orchards School for Troubled Teens, located near the fictional town of Webituck, New York. The institution is run according to a half-baked pedagogical model developed by its founder, Aubrey, an eccentric authoritarian in a turtleneck. It’s hard to tell how kids end up at Roaring Orchards—some appear to be genuinely unsettled, others merely unwanted—but they all are subject to the whims and foibles of their new caretaker. Aubrey’s ideology reads like a mix of Scared Straight and Scientology. “Aubrey actually believes that before you’re born you choose who your parents are going to be,” one teacher explains, “so you’re even responsible for that.” Consequently, daily life at the school has elements of both Lord of the Flies and the Stanford Prison Experiment.

Punishments are arbitrary and often humiliating. Roaring Orchards is a place of creative penal verbs: Children can be “sheeted” (Stripped to their underwear and dressed in a sheet), “ghosted” (treated as if they were invisible), or “roomed” (jailed in the confines of their dormitory). Along with all this crime and punishment, some teaching apparently takes place, with lazy classes run by lazy teachers, seminars with nonsense names like “Cooking With Butter” (English lit, with a focus on The Decameron) or “Humble Starts and New Beginnings” (introductory math). The general mood is one of hopelessness. The finest students dream of escape—the final reward for good behavior.

Our guide in this well-intended catastrophe is Benjamin, dumped at the school by his parents, who claimed they were merely visiting for an introductory tour. Benjamin’s not happy, a point he makes by smashing through the front windshield of their car with his feet. That’s Not a Feeling is rendered in a faulty mixture of first- and third-person narration, alternating between Benjamin’s point-of-view and a wider storyline that he has cobbled together, years later, by talking to the key players and revisiting the campus, which has at this point been abandoned. It’s this authorial decision to toggle back and forth in time that hobbles the novel the most. Benjamin is less a character than a reporter, a dispassionate relayer of cause-and-effect; his psychological baggage (depressed mother, two suicide attempts) is presented as a sketchy afterthought, an excuse for his enrollment. Overall, Benjamin seems to have little internal life, and he’s certainly less interesting than some of his teenage inmates—like “Pancake,” a chubby peer who is given most of the novel’s best dialogue. Benjamin is aloof, disengaged, a floater on the margins of social life. “It’s not that I had any secrets,” he reflects, of his reticence during communal sessions. “I just didn’t have anything to talk about.” Why give the floor to the kid who has so little to say?

That’s Not a Feeling is composed of a series of incidents that add up to very little. Aubrey, mysteriously sick, gets sicker. Benjamin begins a fumbling relationship with Tidbit, a 16-year-old whom he meets, naked, on his first day. There are an odd number of scenes involving encounters with animals, from raging turkeys to cats accidentally set on fire. We are given fleeting glimpses of the school’s underlying philosophy, a malleable thing in the world of Roaring Orchards; at one point, Aubrey delivers a rambling monologue in which he declares, “If you so much as remember ever having been here, I will have failed.”

Roaring Orchards is later turned over to Aubrey’s self-appointed successor, Ken, who preaches “psychic mending” and leads a “ReBirthing session” that provides the novel’s singular, misplaced tragedy. “Of course, what was actually keeping me at Roaring Orchards was that I was being lulled to sleep by the rhythm of the days there,” Benjamin writes, “days that repeated endlessly and were filled with routines that even then had begun to snare me in their impenetrable mysteries.” Those mysteries, ultimately, prove hollow. Roaring Orchards isn’t built on some cultic secret; it’s merely a school run by cruel, incompetent, and ineffective adults. As a result, That’s Not a Feeling doesn’t earn its sense of drama. School sucks, as any truculent 16-year-old can tell you; this one just happens to suck more than normal.

Scott Indrisek is an editor at Modern Painters magazine.