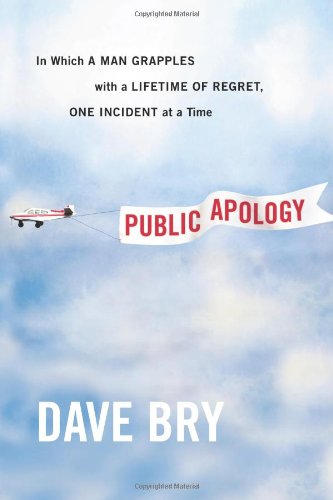

Dave Bry is sorry. For several years, mostly for the New York website The Awl, he's reached back into a sordid, New Jersey/New York past, unearthing misdeeds big and small. If you imagined each of these stories as a moral sustenance, Bry has for years now been serving up dark and funny snacks. Assembled rather expertly for his book Public Apology, they now qualify as something more satisfying, like a turkey dinner on how (not) to live.

Early in the book, Bry recounts a story about visiting Paris, where the young author—then a preteen traveling with his family—watches a horror movie that gives him a screaming fit, and later spits out a bite of a horse-meat hamburger. He is not an easy child to travel with, but he writes about this with modesty, humor, and, most important, control: "It must be a weird thing to go on a trip with your son when he's twelve." I admire the way Bry addresses the reader here and throughout the collection. By implicating us in his folly and his apology, he establishes the depth of his sincerity. He also earns the right to be ecstatic, but this too comes across with sincerity and a wink. "But the buzz and excitement of Paris at night! It really is a beautiful city. I can see why you've chosen to live in it." I don't live in Paris. You probably don't either. But Bry seems to suggest, in a way that sneaks up on you, that maybe we all should, or could—and that we would probably screw up too.

Most of Bry’s essays bear these compelling traits: an entertaining relationship to fallibility as well as short sentences and slyly understated style. His approach does not possess the charming convolutedness and verbal pyrotechnics of writers like John Jeremiah Sullivan and David Foster Wallace, but Bry’s restraint lends his prose its own brand of keenness and charisma. "Do you remember Wendy Sigeler?" he asks in a story about summer camp, emphasizing the elusiveness of memory. "I doubt it, unless she was one of the campers in your cabin. Which I don't think she was. But I can't be sure. I can't actually remember which cabin Wendy was in."

Consider also his apology to a town in New Jersey, where he and his dad nearly killed many when their boat came off the trailer and veered into incoming traffic. The father was long-gone with cancer by this time and couldn't responsibly drive, let alone hitch a trailer properly. The cop who comes to the rescue is pissed, but Bry is even more disappointed in himself—not with some annoying kind of self-loathing but instead a kind of gentle, reasonable struggle with limitation and failure. This is something most of us can relate to. We'll all die. And none of us is ever quite good enough. "[The officer] said that I should drive…. So I did. Like I should have driven there to begin with. Like I should have been able to hitch the trailer to our car and make sure the latch was closed tight, safe, secure."

For all his earnestness, Bry also likes a good cocktail: Half his apologies are about drunkenness, and some of his misbehavior crackles with sloppy humor. When a young nephew calls Bry "fucking bourgeois scum" for living on the Lower East Side, our writer turns to the teenager and says, in front of the whole family, "Suck my dick, you little punk." His apology here is sincere, but one can’t help thinking that it’s overshadowed by the hilariousness of the bad behavior that necessitated it.

The most stirring apology is to Bry's dad, who died under the writer's watch, in less-than-commendable circumstances. Do I forgive Bry? It doesn't matter much. Bry know that total forgiveness and total resolution, as much as he might hope for them, are forever beyond reach. "I still think about it," Bry writes of his final experiences with his dad. You will too.

A former editor at Rolling Stone and the Village Voice, Nathan Deuel is based in Beirut, where he has written essays for the New York Times, GQ, the Paris Review, and Los Angeles Review of Books.