At its most philosophically acute, poetry is dumb. Hölderlin deeply believed this truth, titling one of his great poems “Blödigkeit,” or “Stupidity.” Wordsworth was fiercely attached to his own “Idiot Boy,” insisting on publishing the poem against his friend Coleridge’s advice. Especially today, amid a media culture of rampant knowingness, poetry’s dumbness—its ability to cut through false rhetoric and give us the thing itself—may be its most vital and necessary quality.

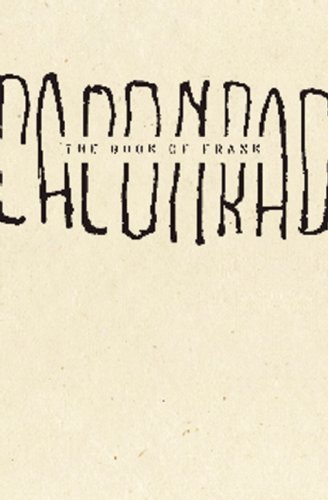

Philadelphian CAConrad is the latest poet to take up the mantle of idiot savant. In The Book of Frank, a sequence of 132 aphoristic poems sixteen years in the making, Conrad follows the caprices of a white-trash wastrel beset by surreal and sometimes violent transformations of self. Like “Huffy Henry” of Berryman’s The Dream Songs, Frank is an alter ego whose distance from Conrad allows the poet the freedom to work through the astonishing traumas of embodiment. In direct, plainspoken language, Conrad creates a world of gothic intimacy and grotesque misdeed (“a dart landed / bull’s eye / on a / testicle // Frank applauded // it was Grandpa”). Tonally, Conrad treats these events with a successful mixture of naiveté and arch hysteria. But it is finally the extreme formal poverty of his poems—the blankness of the white space surrounding them, the haltingly short lines—that makes them effective holding cells. From wounds unflinchingly picked over, Conrad generates moments of clarity and strange grace: “May / flowers // Frank shuts / his legs // but // music // seeps // through”.

To be dumb is to ignore the unspoken rules of the body, a set of codes we call sexuality. Hardly a taboo exists that Conrad does not pervert. Holes are plumbed, gender leaks into its opposite, a marriage is sullied by a husband who marauds his wife’s trash. Curiously, the queer Conrad makes the shape-shifting Frank nominally straight (although gay enough to enjoy being raped by a gang of macho types summoned through “Instant Cowboy Mix”). There is something slightly sadistic about the control Conrad exacts over this vulnerable male hero: the cruelty of the puppeteer abusing his dummy. Yet Frank’s mishandling at the hand of his maker is also heartbreaking. What makes this book “queer”—even more so than its fluid treatments of sex and identity—is the reparative tenderness between the poet and his doppelganger. While Frank’s travails constitute a spectacular freak show, his saga will resonate with any misunderstood (erstwhile) adolescent, betrayed by a body that is always misbehaving. Like certain albums of The Cure or The Smiths, The Book of Frank promises to be a teenage touchstone of hurt writ large, possessing enough hidden art to merit revisiting into adulthood.

Conrad has recently become something of a cult figure in poetry circles. In roving “(Soma)tic” workshops, he espouses ritualized composition practices involving mantras and tombstones. While his witchipoo romanticism may verge on the corny, Conrad’s approach is a welcome change from high-minded poetry that steadfastly ignores the body in all its dumb, limiting materiality. Rimbaud declared that “I is another”; Conrad’s work shows us that the body itself is the first source of alienation and estrangement from the self, and is thus the true subject of poetry. Only by engaging this body, by forcing ourselves to travel through the shames and humiliations of its portals, can we achieve transport.

Christopher Schmidt is the author of a book of poems, The Next in Line (Slope Editions, 2008).