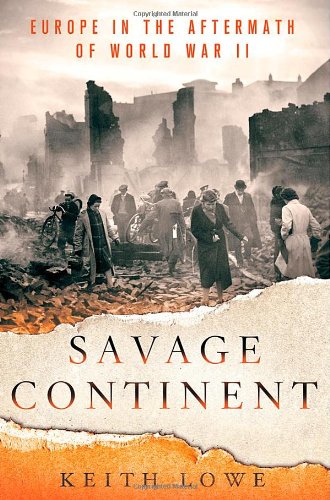

While the history of WWII is common knowledge, fewer people are aware of what happened in Europe right after the armistice was signed. In his new book, Keith Lowe, the author of two novels and a well-received account of the bombing of Hamburg in 1945, delves into the four years immediately following the war, and what he finds isn’t pretty. Much of Savage Continent reads like a non-fiction version of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. Chapters are devoted to, among other subjects, physical destruction, famine, moral dissolution, and revenge against collaborationists. Only one chapter, on hope, interrupts the darkness.

“[T]he war did not simply stop with Hitler’s defeat,” Lowe writes. Between 1944 and 1949, “a conflict on the scale of the Second World War, with all the smaller civil disputes that it encompassed, took months, if not years, to come to a halt, and the end came at different times in different parts of Europe.” The Soviet Union consolidated its control over Eastern Europe, entire populations were ethnically cleansed, and Jews and other minorities found themselves unwelcome in their homelands. Another way of putting it, as Lowe does, is that these atrocities were the last spasms of the war, and perhaps should even be considered part of WWII itself, even if states weren’t formally at war. Lowe’s book is an account of the dreadful aspects of that era. One would never know from reading Savage Continent that the early post-war years also saw the Nuremberg Trials set the standard for international justice; that the United Nations’ first meeting was held in London; or that the Marshall Plan economically reinvigorated Western Europe.

“Vengeance is a constant theme of this book,” Lowe tells us. Indeed it is. During this period, every country in Europe—including Germany—believed itself to be wronged in some way, and each wanted to vent its anger. Often this took the form of state-sanctioned violence, such as the expulsion of Germans everywhere from Poland to Yugoslavia. But perhaps more disturbing was how individuals took matters into their own hands. Liberated Jews and citizens of formerly occupied countries were often permitted to seek revenge on their former tormentors. Women who slept with German soldiers were humiliated in the streets. Writing about these incidents, Lowe treats his subjects with empathy, but refuses to engage in moral equivalencies. He portrays the Allies as flawed liberators and the Nazis as monstrous—though not the only monsters operating at the time.

In corralling this history, Savage Continent draws upon multiple archives across Europe, from London to the former Soviet Union. Lowe translates Polish and Ukrainian documents, and taps Czech and Slovak sources to reveal new perspectives on the era. His focus also extends beyond Western Europe, showcasing his extensive knowledge of the Greek Civil War, and of the Communist terror in Romania.

Many books have focused on WWII’s legacy in individual countries, or the politics of revenge. Think of Istvan Deak’s edited collection on The Politics of Retribution in Europe. But Lowe’s is the first to compile a short-term history of all of Europe’s mayhem after 1945. The closest analogue, Tony Judt’s Postwar, only briefly touches on these years as part of a larger attempt to chronicle European history from 1945 to the present day.

Savage Continent is an admirable achievement, though occasionally it's easy to get lost in the details. Lowe writes that Poland suffered the most proportionally as a nation—more than one in every six Poles was killed. In the very next paragraph, he writes that the “Belarusian death toll is reputed to have been the highest of all, with a quarter of the population killed.” He repeats the well-worn anecdote about Winston Churchill denouncing Stalin’s ‘joke’ that at least 50,000 and perhaps 100,000 members of the German Command Staff should be liquidated, and Roosevelt’s reply that a compromise could be reached by killing 49,000 of them. “If one takes Roosevelt’s comments at face value, and factors in the President’s well-known anti-Germany prejudice, then he begins to appear every bit as ruthless as Stalin,” Lowe writes. In instances like this, Lowe can burrow so deeply into his topic that he seems to loses perspective.

Still, for every flaw, fifty brilliant facts and quotations are unearthed. Perhaps the most mind-boggling is the man who suffered through both Auschwitz and a Polish concentration camp: “I’d rather be ten years in a German camp than one day in a Polish one,” he stated. Such a line demonstrates how little is popularly known about so much of the years following the war. Lowe modestly states in his introduction his book is merely meant a sampling of the European postwar period. But at it stands now, his book is the only one on its subject, and it makes a valuable contribution to our understanding of WWII and the postwar era.

Jordan Michael Smith is a Contributing Writer at Salon and the Christian Science Monitor.