Line Dancing

Saul Steinberg couldn’t fully enumerate the contents of The Labyrinth in words. For a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1978, he composed a list of the subjects explored in the book of drawings, originally published in 1960 and recently reissued by New York Review Comics. It begins with “illusion, talks, women, cats, dogs, birds, the cube” before trailing off, a dozen items later, with “geometry, heroes, harpies, etc.”

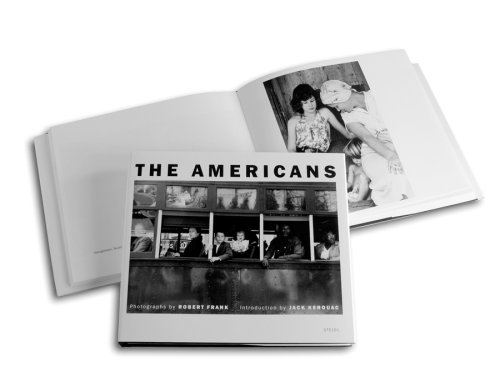

The title, too, gave Steinberg some trouble. He took several trips by car and bus throughout the United States between 1954 and 1960, during which the book’s