Over the past thirty years, Geoffrey O’Brien has devoted his attention to many subjects: He is the editor in chief of the Library of America, has published several volumes of poetry, and has surveyed a broad range of cultural provinces in books such as Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir (1981) and Sonata for Jukebox: An Autobiography of My Ears (2005). He has written about multiple art forms and genres, moving effortlessly from Heinrich von Kleist to comic books, from La Traviata to Burt Bacharach. And through it all, he has revealed his love for the movies, proving himself to be one of our most valuable writers on the seventh art. O’Brien has covered film for an array of publications, notably the New York Review of Books and the Criterion Collection’s supplemental booklets (he is also a longtime contributor to Artforum and Bookforum). Because he operates outside of the staff-reviewer grind, his immaculately polished prose bears no traces of deadline pressure, and his wide-aperture historical perspective lends his writing a vital charge.

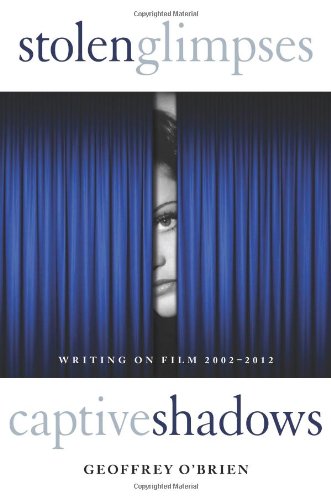

O’Brien is not one to sound the alarm that cinema is ceasing to matter (as some critics have lately), even as he notes viewers’ changing habits. Indeed, his new book, Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows: Writing on Film, 2002–2012—which essentially picks up chronologically where his last mostly movie-related collection, 2002’s Castaways of the Image Planet, left off—often seems to suggest that the golden age of movies is whenever you sit down to watch one that’s made to last.

In Stolen Glimpses, long-form new-release considerations rub shoulders with essays on whatever new biographies or home-video restorations gave O’Brien occasion to rhapsodize about his old favorites. That’s not to suggest that revisiting the classics is a new part of his program. Midway through his remarkable 1993 book, The Phantom Empire, O’Brien gives a circuitous version of the emergence of the auteur theory, in which every movie worth its salt represented its maker’s “personal philosophy bounded by barbed wire, broken glass, and trained attack dogs.” Thus viewed, these Great Directors’ works became worlds in and of themselves: “In Fritz Lang’s early movies you found not Germany but what he had substituted for Germany. John Ford constructed a scale model containing all he wished to preserve of civilization—a portable world in which John Wayne and Ward Bond could swap drinks and war stories until the end of time.”

He might now poke a little fun at the youthful zeal with which he internalized this theory, but O’Brien has nonetheless continued to go back to the works of his beloved directors, returning again and again to their sovereign territories just to see what else might turn up. In the new volume, master of “permanent emergency” Lang once again sits alongside the more plainspoken Ford. Here, O’Brien also spools up Breathless on its fiftieth anniversary, determining that the spell it cast on him as an adolescent will never really wear off; he lavishes attention on Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol, Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes, and Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, unassumingly supplying readers with reasons why they might treasure the films under discussion as much as he does.

If these dispatches are short on spirited contentions (the occasional judgments don’t get much more provocative than when he declares certain neglected films to be “underrated”), they display an extraordinary sensitivity to what, exactly, is transpiring on-screen. O’Brien does not merely report with accuracy what he sees, but tunes in to more elusive frequencies, sounding out films’ highly individual use of elements of space and time. In the opening of the 1937 American drama Make Way for Tomorrow, the soon-to-be-evicted elderly couple “exud[e] the weight of a long life lived in one place; and even as we absorb that information we are watching fifty years of stability ineluctably dissolve under the influence of another kind of time: the time in which loans come due before they are ready to be paid”; within the locations of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, “there are openings to further spaces,” including “the inner lining of a shoe exposed to demonstrate its shoddiness,” “the picture of Mount Fuji over the sea drawn by the kidnapped child,” and “the murky hidden worlds of bars, drug-ridden alleyways, and cheap hotels.” To O’Brien, not only is each auteur’s body of work a world unto itself, but so is each movie, and he excels in feeling out the terrain.

As ever, his reeling poetic style is perfectly suited to capturing film’s fugitive qualities—its fleeting enchantments, and its slippery relation to moments both past and present. Movie writers often turn a blind eye to the experience of watching, but it plays a central role in O’Brien’s criticism, such that he conveys an intimate sense of his impressions as they’re registered. The book’s brief preface provides a particularly fluid state of the medium from the angle of the audience: “To hang suspended in air, see through walls, fly over cities and peer unseen at their inhabitants, go back in time: these must be in some sense illicit pleasures. Movies are the banal miracle, an achieved magic to which we have almost become inured.” In a later essay, O’Brien sees early cinema, viewed today, as eliciting its own kind of vertigo, with films as “points of contact” between director and spectator that “seem like glances exchanged between people in different cars moving in different directions.” Even as he describes the real-world circumstances under which he first encountered certain movies (a common entry point here), or connects one plot point to another, O’Brien often finds himself haunted by afterimages: “With Tourneur you cling in memory to a vivid but uncapturable sense of place and mood, like a scene from early childhood or from a dream that even though only half-remembered lingers stubbornly in mind.”

The pieces here are arranged in order of publication date, so O’Brien’s sojourns back into cinema’s seemingly inexhaustible history are regularly offset by more present-tense engagements. The book’s structure neatly spotlights the author’s interpretation of the major film-culture events of the last decade: An early piece marks the death of Pauline Kael, while a 2012 Film Comment blog entry prizing the legacy of Andrew Sarris serves as a slim outro. In between, O’Brien manages to cover both the penultimate and final films of French New Wave elder Eric Rohmer, the essay on the latter, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon, being one of the volume’s most involving, combining the author’s ritual archivism with the more utilitarian urgency of his current-cinema championing.

The selection of twenty-first-century theatrical premieres examined here otherwise feels a little miscellaneous: O’Brien watches material familiar from his adolescence as it’s pulped by the demands of industrial filmmaking (Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man, Spielberg’s War of the Worlds), gives a fair shake to unlikely juggernauts The Passion of the Christ and Fahrenheit 9/11, and praises directorial ambition where he’s able to find it. Though he occasionally overreaches (such as when he likens Beasts of the Southern Wild’s “watery element” to L’Atalante’s), O’Brien is most at home in this latter mode. The Waco sections of The Tree of Life present “the world as processed by the mind, with finally only the bright bits magnetized by emotion remaining to flash against the darkness”; in The Master, “personalities are treated as landscapes, or forms of brooding music: harboring all sorts of odd crevices and fissures, and capable of no end of abrupt unforeseen mutations.”

It’s impossible to come to the end of Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows without wondering what the author might have made of the contemporary films he skips over. An assessment of Bill Morrison’s 2002 Decasia, a found-footage inferno of decaying celluloid, might have perfectly complemented the volume’s dyad of nonalarmist (but still apprehensive) fate-of-silent-cinema meditations, and certainly would have presented O’Brien with a golden opportunity to apply his formidable descriptive abilities. (J. Hoberman wrote that “few movies are so much fun to describe.”) O’Brien wouldn’t necessarily have much patience for the masculine codes that govern Michael Mann’s universe, but one might also wonder what the author would have to report after poring over the pixelated midnights of Collateral, Miami Vice, and Public Enemies.

Then again, as much as we might want O'Brien to weigh in on more of the last decade's standouts, it’s easy to celebrate his decision to focus here on films he truly cares about. He devotes himself fully to the movies that he writes about in Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows, carefully relating back his insights from each close viewing. And he has bigger things on his mind than surveying an industry in flux—he's still wending his way back and forth through the maze of his personal canon, pinning down its quicksilver images as best he can.

Benjamin Mercer is a copy editor at Bookforum and reviews movies for the L Magazine.