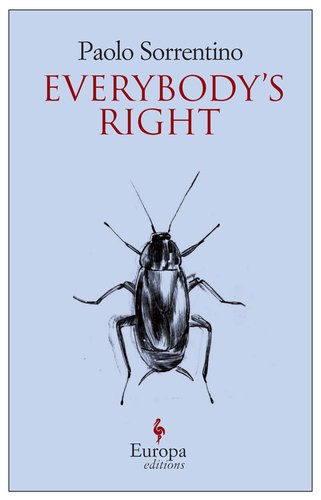

Had the filmmaker Paolo Sorrentino been born a few decades earlier, he’d have enjoyed widespread Stateside buzz. His 2008 Cannes prizewinner, Il Divo, would’ve been an art-house smash, and this year he would’ve done still better, with the Sean Penn vehicle This Must Be the Place. Nowadays, however, European film must glean the leftovers outside the multiplex, as even a figure like Almodovar struggles for US distribution. Small wonder, then, that a creative spirit like Sorrentino has turned his back on success as defined by the Industry—even in his first novel, Everybody’s Right. The narrative’s experimental, its plot helter-skelter, its morals and mores cynical, its point of view limited to a highly singular narrator. The milieu’s largely European, so that one thinks of the dwarf musician relating The Tin Drum, and of the hopelessness pervading The Elementary Particles. That’s fast company for any novelist, and Sorrentino doesn’t always keep up. Still, his debut raises an ameliorative stink, a bracing alternative to the staleness of formula, whether on a downscale Italian tour, wandering a Brazilian shantytown, or sinking into a Manhattan mashup of showbiz and sleaze.

This newcomer to language-based art starts off, impressively, with a riot of language. In just a few pages, an aging musician takes his place alongside classic curmudgeons like Svevo’s Zeno, snarling unapologetically through a list of “Everything I can’t stand.” Funny nuggets gleam here and there (“Such good manners, such a smell of death”), and throughout, one has to admire the translator, Antony Shugaar, bringing off near-oxymoronic juxtapositions, veering from the rococo to the slangy. Yet the catalogue’s sheer heft matters more than any detail; this maestro hates everything—with the exception of his odd final item: “Nuance.”

Everybody’s Right, thereafter narrated by this man’s most successful apprentice, follows the master’s lead. Tony Pagoda has escaped hardscrabble Naples by dint of his songs and singing. He’s enjoyed Stateside buzz, and the first chapter finds him in New York, visited backstage by Frank Sinatra. Yet if that scene recalls Sorrentino himself, who likewise climbed the ladder of the arts out of Naples and onto the A-List, one hopes the filmmaker relied on his imagination for chapter’s conclusion, in which Pagoda’s first serviced and then robbed by a trio of Times Square whores.

The novel never returns to Manhattan, or indeed stays put anywhere. One chapter takes the singer on the Italian equivalent of the state-fair circuit, and the next puts him through raucous squabbles with friends and family in Naples. Throughout, the effect is of a roller-coaster, rather than of gathering momentum. Episodes don’t raise questions about what happens next, or what makes Pagoda tick, so much as bowl us over with bravura detail—with nuance, actually. Consider, for instance, the jeweler’s eye at work in the opening encounter with Sinatra:

Frank . . . extends his hand, upon which there sprawls a ring that lists at 122,000 dollars. An orgasm of diamonds. I reply with my thirteen-million-lire ring, one tenth of the value, purchased from the goldsmiths on Via Marina. The two hands clasp. The rings touch with a clinking sound that nobody misses. . . . Titta [Pagoda’s guitarist] looks down at his wedding ring, humiliated, and at the most important moment of his life, underwriting new and previously unexplored inferiority complexes.

Most episodes in Everybody’s Right climax in a similar apercu. The insights don’t build on one another, we’re neither unfolding a mystery nor exploring a personality, and nearly all the epiphanies take us to despair. On those occasions when Pagoda seeks human warmth (he’d usually prefer a line of cocaine), he must settle for the slap of naked bodies or the tattered pleasures of a city in collapse. He serves up the picaresque of a streetwise Candide, always randy (“my mind was clouded by the dictatorship of my genitalia”), obstreperous (“she’s a shitty cook . . . with . . . dishes that border on death”), and nihilistic (“Adult life is an infinite repertory of grief and pain”).

Exceptions? Glimmers of nobility? In the first place, the wailing and scorn tends more toward Jerry Lewis than Job, and their whole-throat vivacity often trumps the pervading misery. The reminiscences never amount to a bildungsroman, and Sorrentino never satisfactorily evokes love—Tony’s Beatrice, supposedly his donna del cuore, remains more abstract than Dante’s. But then again, he brings off convincing subtlety in the run-up to Tony’s deflowering, at the hands of a fallen but fascinating Neapolitan aristocrat. Later, the novel takes its most startling turn at the singer’s sudden retirement while on tour in Brazil, and when he moves up-Amazon to Manaus, there’s a favela excursion that smacks, briefly, of redemption.

But if the Brazilian outback makes a temple of this Pagoda, Sorrentino doesn’t allow it to stand. In the final chapters he whisks his protagonist back to the Bel Paese, as the house singer for a Berlusconi stand-in. Tony ends up in a life of infinite license, where “everybody’s right,” yet he remains cursed by his special brand of integrity; he can’t ignore how, beyond the villas of the superrich, “it’s all just one huge rape.” Such social critique earned the novel considerable praise over in Italy, and this filmmaker’s energetic wallow in prose does seem best appreciated as a cry for the beloved country, resonating off touchstones from The Divine Comedy to “Bunga Bunga.”

John Domini’s most recent novel is A Tomb on the Periphery. See johndomini.com.