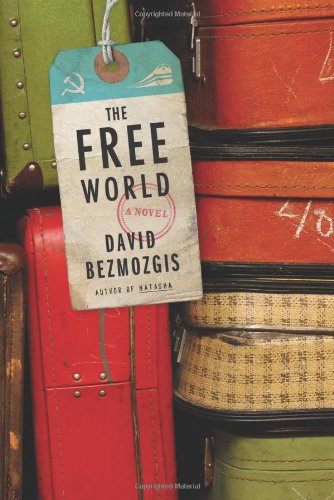

In the past decade, a handful of writers have added compelling twists to the classic immigration novel, adding new and unexpected layers to tales of newcomers in new lands. Jeffrey Eugenides, for example, wrote about a hermaphrodite immigrant in Middlesex; in Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the protagonist had a fantastic imagination and used an unexpected language infused with Spanish and video game slang. Now comes David Bezmozgis’s The Free World, an immigration novel in which the characters don’t actually immigrate.

Instead, the book, set in the 1970s, focuses on the long, befuddling months that one Latvian family, the Krasnanskys, endure in Italy, waiting for documents that will allow them to immigrate to Canada (their first choice was the United States, but they switched, believing they would be processed faster). They have just escaped the Iron Curtain, along with thousands of other Soviet Jews, but now they are stuck in Rome, unable to go forward or back.

The family’s patriarch, Samuil, has somewhat unwillingly followed his grown sons and grandchildren out of his home country. Back in Latvia, he was a successful Communist Party member with his own chauffer and factory. Now, he sits at the dining room table of a cramped suburban home, writing a memoir and questioning his decisions. Karl, his oldest son, quickly networks with other Russian émigrés—many of them lifelong criminals—and sets up shady but profitable auto-body and real-estate businesses. Alec, the youngest son, is a romantic dreamer, unsuited to a world that requires him to sell antique Latvian classical records on the street, or attach a string to a coin, so he can yank that coin back from a payphone once his call is done.

In many ways the novel fits in the Russian tradition; it’s full of extended family and nicknames and sprawling connections that link characters back to childhood villages. The concept of non-immigrating immigration has the absurdist touch of Gogol, but The Free World doesn't have Gogol's satirical tone. Bezmozgis was recently named one of the New Yorker’s 20 under 40, and displays a deep compassion for his characters. (This quality is also evident in his short story collection Natasha and Other Stories; if you haven't read it, you should stop reading this review and run to a bookstore immediately). Each person in the rambling Krasnansky clan is explored in detail and with keen insight, which Bezmozgis achieves with dazzling manipulations of point-of-view. Though the novel follows the inner lives of Samuil, Alec, and Alec’s new wife, Polina, the other characters are described so closely through these three’s impressions that you not only understand them, but feel you know them intimately.

Structurally, the story moves in two ways. Via Samuil, the plot goes back in time, exploring his life, which also happens to dovetail neatly with the history of the Soviet Union: from his father’s murder by Czar-loyal White Russians, to the conversion of Latvia to Communism, to the battles against the Nazis during World War II. Via Alec and Polina, the story moves forward, charting how each family member learns—or doesn’t learn—to adapt to the West. Karl’s children, for example, were raised as atheists, but are swept up by Italian rabbis who teach them Hebrew songs and arrange economic perks for the whole family (as long as they go to synagogue).

Samuil’s reflections on the past are sometimes fascinating: He remembers “the burning and undernourished faces of the girls on the [Soviet] education committee, folding pamphlets late into the night after twelve hours at their sewing machines. Their pale, quick hands, their frayed coat sleeves, their serious expressions…where are they in the record of history?” But all this looking back drags the momentum of the novel, diminishing key questions such as: Will the Krasnanskys ever get their papers? And do they even want them anymore?

The novel's construction foregrounds the tedium of the character's particular purgatory: As the Krasnanskys wait and wait, the reader waits and waits with them. On one hand, this is an ideal structural commentary on the immigrant condition—the burden of history weighing on an individual’s future. On the other hand, it really slows the book down.

By the end, The Free World comes together with a violent incident that rings true in the best way; you have sensed the event coming, but couldn’t have predicted the way it unfolds. Further, it perfectly clarifies what Bezmozgis explores so well: the ways that people try to survive, and how some succeed while others fail. In this sense, moving from one country or political system to another means little. Human nature—and human weakness—is what defines a person.

Leigh Newman’s memoir about Alaska, Still Points North, is forthcoming from Dial press. Her work has appeared in Tin House, One Story, and The New York Times’s Modern Love column.