Remarks from the dedication of the Donald Barthelme Papers to the University of Houston Library, April 15, 2005.

Don Barthelme once said to me, “The trouble with teaching is you spend all your time working on someone else’s rotten manuscript when you should be working on your own rotten manuscript.” This is signature Barthelme. It contains the making of a joke by repeating two syllables or two words or two phrases, at which he was very good: “And I sat there getting drunker and drunker and more in love and more in love.” Sometimes the two words are so good you do not need repeat them for the joke to obtain. One night Don’s wife, Marion, reported, not without a tinge of worry, that the neighbor’s dog had nipped their child. Don said, “Does she warrant it not rabid?” Warrant and rabid had not been heard in a while; their archaic novelty was funny and gently suggested we not worry overmuch in our modern bourgeois fatted travail. “Does it have rabies?” would not have managed this humoring balm. Another time Marion reported that a strange young man had come to the door, vaguely menacing somehow—“Did he have a linoleum knife in his pocket?” Don said, nearly laughing himself. “Rotten manuscript” also contains his careful self-deprecation.

The repetition surprises twice: we do not anticipate a prudent teacher’s calling a student’s manuscript rotten, and we certainly do not anticipate Don Barthelme’s calling his own manuscript rotten. He was always prudent to not promote himself in just this way. If he praised himself, he detracted, and the praise was seen to have been but a setup. One night he said, “I am going to read a story called ‘Overnight to Many Distant Cities,’ a lovely title I took from the side of a postal truck.” This capacity, this tendency to what he called “common decency,” lifted him from the mortal street where he was a pioneer writer—arguably, I think, one who began with “bad Hemingway” (cf. Paris Review interview) and refracted that through Kafka and Beckett and Perlman and Thurber and changed the aesthetic of short fiction in America for the second half of the twentieth century in equal measure to the way Hemingway changed it in the first, and Twain before that—well, from this high mortal street to, in my eyes at least, a kind of high mortal deity. Don was God here in Houston, loved by some of us and not by others, like all gods, and if he was not always godly he was always goodly to us. He was a Biggie and he was goodly. He was a strange New York Biggie who was, even more strangely, from here, and he was back with some benevolent plan. It had a powerful effect. We were lowly sun-addled Aztecs to his Quetzalcoatl, and it felt like we’d been waiting for him a long time without knowing it.

In my own case we entered into a special affair when I discovered by accident that if you demanded good fathering of him, he who spent a third of his time writing about bad fathering, a phrase he considered redundant, he would oblige you. The day we met him, he came up on Glenn Blake and me to shake hands and trapped us in tiny school desks we couldn’t get out of quickly. We struggled to get up and stand as boys with proper manners would—here came Andy Warhol, in an urban-cowboy suit, on a slight vodka tilt, bearing down on us, and we’d better stand up. He saw us trying to be good boys (he did not see that we were caught so flat-footed because our previous teacher here would not have deigned shake hands with us). Within a few weeks I was saying to him in a manuscript conference, “Don’t you ever withhold a comment from me. I am not here to be coddled. I came here to meet women. And I am not going to write a thesis. If I have to do this I am going to write a book.” “By all means,” Don Barthelme said, chuckling, closing the manuscript, both of us chuckling. A boy demanding more rigor, not less, of a father! A man who theretofore felt all fathering tantamount to botching and bullying! We gave it a try. I have said all this tonight because I did not say any of it at the funeral. I avoid funerals and weddings.

I am going to read a Barthelme story. The trouble with reading someone else’s story is that you have spent all your time reading your own stories messing them up and no time reading someone else’s stories messing them up. It makes you nervous in a new way, especially against the chance that some of you might have heard Don Barthelme mess up reading his own stories. That was some powerful, crisp, deft, nuanced, trippingly enunciated, princely timed messing up that made you laugh not only at that which had not struck you as funny when you read it, but at that which you had not even sometimes understood. On a night when he had asked if the neighbor’s dog was warranted to be not rabid, or if the boy at the door carried a knife, this story—the story I am going to mess up reading—was handed to me in manuscript by Don Barthelme, who said, “Here. My latest.” He was showing me how it actually worked, or that it actually worked. When we saw one of his stories in the New Yorker we thought it had sprung full-blown from on high. I was to see that it started on unspoiled paper and you spoiled the paper by typing very neatly with good margins and no mess and sent it to Roger Angell and then it looked the way it looked in the New Yorker. The paper was spoiled on that typewriter over there by the door where the boy with the linoleum knife and the boy who had disappointed us by not having a linoleum knife had tried to gain entry. There were water marks from the stem of a glass on the wood by the typewriter.

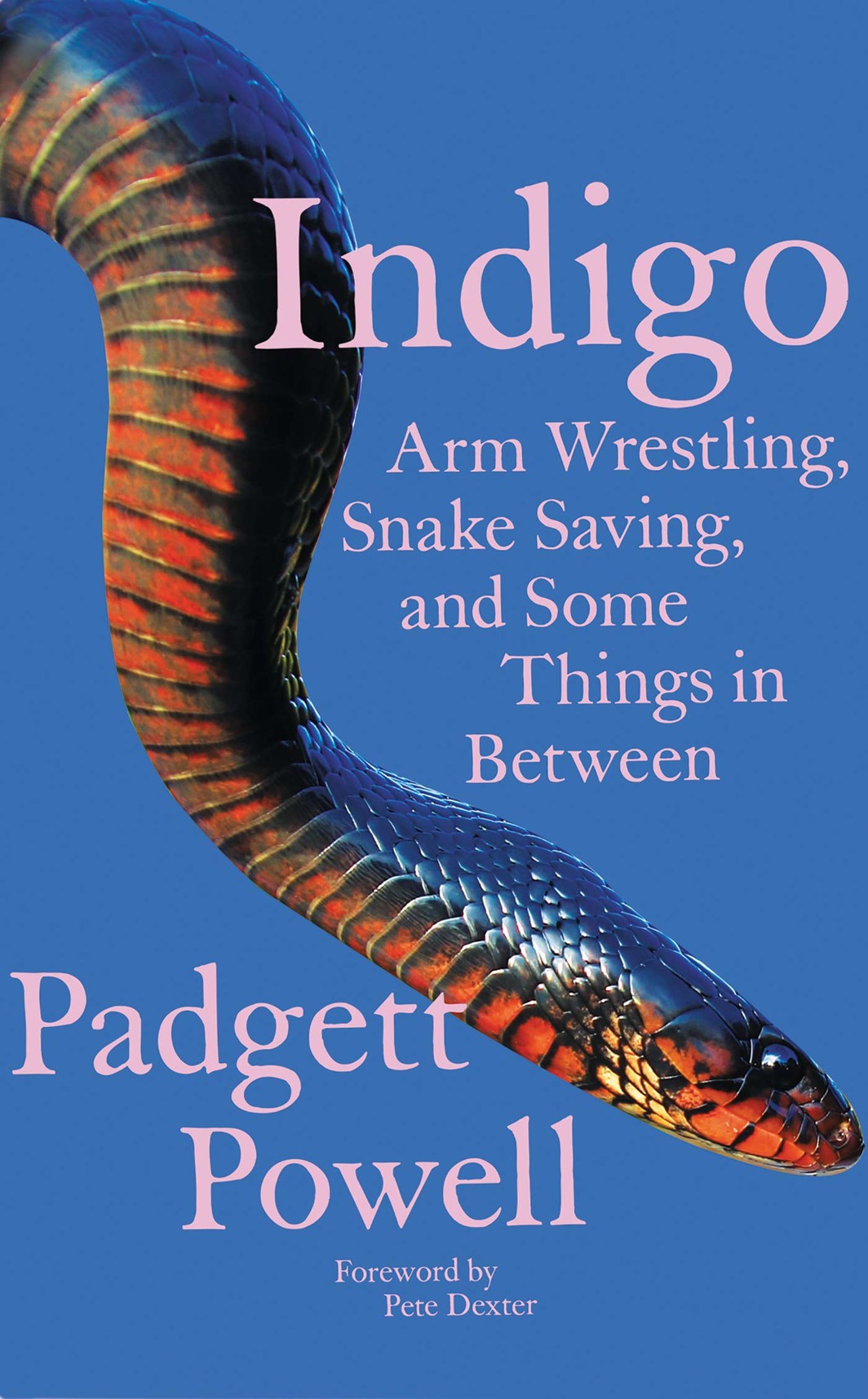

Excerpted from Indigo: Arm Wrestling, Snake Saving, and Some Things in Between, an essay collection by Padgett Powell published by Catapult Books in 2021. A version of this essay was first published by McSweeney’s. Copyright Padgett Powell.