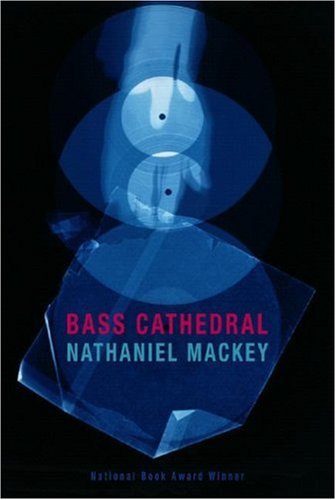

In Bass Cathedral, the fourth installment of Nathaniel Mackey’s epistolary novel From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate, the author plots language’s intimate relationship with music, the point where sound and sense meet. N., the series’s reedman and trumpeter, continues to chronicle the musical, intellectual, sexual, and supernatural exploits of the jazz group Djband (né the Molimo m’Atet, the Mystic Horn Society, and the East Bay Dread Ensemble, among others) in his letters to a correspondent known as the Angel of Dust. This volume finds the band in the wake of their first record release, bemused by the appearance of cartoon speech balloons bearing enigmatic text that sprout from the players’ horns and bass and even from the grooves of the record itself.

As in the previous books, plot serves as a platform from which Mackey launches a volley of poetic and philosophical concerns. His recourse to the deep history of African diasporic music and his unique insight into its iconic performances lay Bass Cathedral’s foundation. Meditations on Dizzy Gillespie’s predilection for the vowel sound “oo” in his scatting and Joe Henderson’s flubbed early entrance on Andrew Hill’s “Refuge” offer a portal to N.’s inner life and grant access to the border between song and consciousness. The most vivid passages, however, are those depicting fictional pieces by Djband. In one such letter, which describes a bass solo that resonates with the book’s title, Mackey’s uncommon imagery and lyric line perform the music they depict: “She thumped with her thumb and with the heel of her hand, sometimes one, sometimes the other, a now halting, now hortative colloquy of thump and strum. Leaning over the bass, hunched over the bass, she increasingly made a cave of herself, an esoteric recess whose bodily husk housed rhythmic disbursements of thump and strum. Colloquy and cave rolled into one, she and the bass effected a unified or unitarian house of sound, a first antiphonal church of thump-inflected strum.” The repetitions of thump and strum lay down a walking bass line tied together by the repetitions of sometimes and now, syncopated by the staggered alliterations of hand, heel, halting, hortative. The sentence swings even as it portrays swing.

The passage also demonstrates a vector common in Mackey’s writing. What starts as a concrete image (a bassist playing) transmutes over the course of three sentences into a sublimely abstracted fusion—“Colloquy and cave rolled into one.” The posture of the player becomes a cave, and then a church. Her two modes of attack are a colloquy; the colloquy becomes antiphony. Thus a complex and asymmetrical image, one of eccentric beauty, is born.

That these idiosyncratic yet rigorously applied thought processes never become overly cerebral is testament to Mackey’s tremendous musicality. Such is the exquisitely rhythmic lyricism of the novel that not once does the conceptual language dampen the sound of the music inhabiting the prose. With Bass Cathedral, Mackey writes into being a fiction worthy of the songs he interrogates.