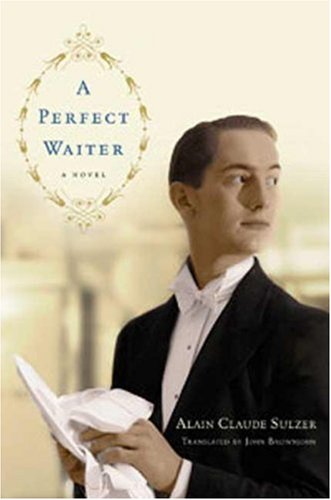

The setup is almost a cliché. Thirty years after the love of his life left him for a wealthy, more promising man, Erneste finally receives the letter he has waited for in quiet desperation. Although he can think of nothing else, he resists opening it for two days. When he eventually reads it, it devastates him. His former lover wants money. Before Erneste can get his bearings, another letter arrives, stripping “off a few more layers of scar tissue. Outwardly he was calm, but an explosion had taken place inside him.” It is in that gap that this sleek, understated novel’s interest lies: However great the inner turmoil, appearances rarely waver in Swiss novelist Alain Claude Sulzer’s A Perfect Waiter. With the ominous letter, Sulzer draws the reader into Erneste’s constricted interior world, then sets one charged revelation on top of another. This novel, Sulzer’s fourth, is a highly choreographed waltz of emotional blackmail. It skirts melodrama, but Sulzer’s restraint in depicting each subsequent betrayal keeps the raw emotions in check.

Erneste is a perfect waiter. Self-effacing to the point of being a cipher, discreet, attentive, and tactful, he serves a luxury hotel’s demanding clientele with effortless grace. For all his popularity, the guests know him only as Monsieur Erneste. It never would occur to any of them to ask after his last name.

His inner life is controlled as carefully as his facade. To escape his family’s disapproval, Erneste left his small Alsatian village at sixteen and quickly worked his way up through the hierarchy of hotel staffing. Five years later, he has made himself indispensable at the Grand Hotel, a luxury resort in a Swiss mountain village. News of his parents’ deaths leaves him indifferent. The freedom to live as he chooses, no matter how constrained his realm, has erased any trace of familial affection. Erneste pursues occasional affairs, sometimes even with hotel guests, mostly noblemen of a certain age. It is there in the hotel, in 1935, that he suffers his coup de foudre. A nineteen-year-old apprentice waiter, Jakob Meier, arrives, and Erneste contrives to take charge of his training. They are lodged together in an attic room, soon an idyll of passionate love.

There are signs, which Erneste resolutely refuses to see, that the idyll is doomed. The hotel’s atmosphere is clouded with apprehension as the first waves of wealthy Jewish refugees arrive on their way into exile or hoping to wait out the approaching storm. But Erneste’s storm breaks first, when he discovers that Jakob had been prostituting himself to a venerable German writer, Julius Klinger, who is escaping to America after denouncing the Nazis in print. Jakob leaves with Klinger and disappears without a trace.

By the time Jakob’s letter arrives, in September 1966, Erneste has perfectly melded a life of waiting for Jakob with a life of waiting on others. Although he knows Jakob is lost to him, he has enshrined those few months of complete emotional and physical intimacy in his heart and deadened himself to all other feelings. Trading on past affection, Jakob begs for money, if not from Erneste himself then from Klinger, who has, by chance, settled in a nearby village.

Sulzer winds three story lines of differing pace and duration together until Klinger’s cataclysmic revelation. And each return to a narrative thread brings brighter color to the studied gray Erneste has cultivated in his emotional range. Sulzer’s style is simple, almost minimalist. Emotion lies in what’s unsaid. After Erneste finally musters the strength to resist Jakob, he makes one of his occasional forays to cruise the park’s public toilets. Caught up in his internal drama, he misses the usual danger signs and is brutally beaten by some homophobic thugs. His habits of emotional constraint are so ingrained that even as he is beaten nearly unconscious and doused with streams of urine, he observes himself from a distance: “Although he was lying helpless on the floor, he took a long stride, and after that he found himself in another world, and every succeeding blow reinforced his position in that other world.” But the most poignant moment comes in the two sentences that close the scene: “When he awoke the next morning he made up his mind to pay Klinger a visit. He wouldn’t write to Jakob for the time being.” Hatred and humiliation have swept away Erneste’s hard-won resolve to assert himself.

German reviews have made much of Julius Klinger’s resemblance to Thomas Mann and the mountain hotel’s to the setting of The Magic Mountain. Klinger is obviously modeled after the great writer. But to insist on such connections is misleading. Sulzer’s mountain is intentionally mundane, and he has quite effectively created an egocentric, conflicted, and immensely talented master for his own purposes. To some extent, Mann’s fiction paved the way for work like Sulzer’s. Sublimation, style, and metaphysical conceits enabled Mann to create art palatable to the early-twentieth-century bourgeoisie out of such fundamental taboos as pederasty. Sulzer addresses homosexual desire directly, exposing the damage severe repression brings.

There is no sense of catharsis, liberation, or redemption at the close of A Perfect Waiter. Erneste stares out over the lake after a steamer, just as he did on the day Jakob left. Erneste’s nostalgia for his brief but perfect happiness with Jakob is tainted, transformed “into the undignified whimpering of a dog that dreads its master’s blows as much as it craves them.” It seems unlikely that the small fund of pleasure his memories of Jakob brought was worth the cost of treasuring them. Suffering has not made him a better person; he has merely suffered.

Yet in detailing the course of Erneste’s suffering, Sulzer has written an absorbing miniature. He so thoroughly inhabits Erneste that the waiter’s muted inner life proves more gripping than the overtly dramatic scenes of betrayal and attempted extortion. It is the whisper, not the shout, that grabs the attention.

Tess Lewis is an essayist and translator who writes frequently on European literature.