Honor Moore could be said to walk barefoot on broken glass in her poems as well as in accounts of her family history, as though discovering hidden truths were a searing ordeal. Pain is a dark radiance in Moore’s work, but it is subsumed by the strong current of her curiosity, by compassionate analysis, and by pleasure in expressing complex feelings in supple language. And not only are her tales of family dramatic and provocative, they also compose a microcosm of American history.

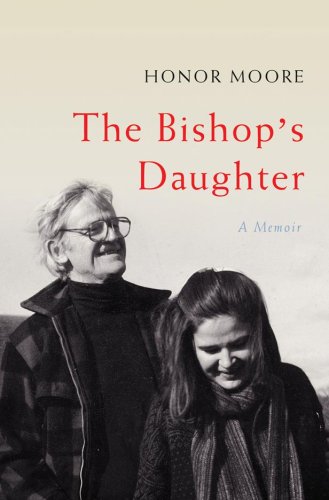

In the biography The White Blackbird (1996), Moore portrayed her maternal grandmother, Margarett Sargent, an accomplished modernist painter brought down by manic depression and alcoholism. Following two nervy and sensuous poetry collections, Darling (2001) and Red Shoes (2005), which offer frank insights into her complex inheritance, Moore continues her family chronicle with a memoir, The Bishop’s Daughter. In this multifaceted narrative, she focuses on the private dimensions of the demanding and influential public-service lives of her mother, Jenny McKean, and father, Paul Moore Jr., the famously liberal, activist Episcopal bishop of New York during the tempestuous ’70s and ’80s.

In their youth, Jenny and Paul moved within the same blue-blooded circle. Jenny’s antecedents include Thomas McKean, a Declaration of Independence signatory, scientist Louis Agassiz, and painter John Singer Sargent. Paul was the “beneficiary of vast wealth,” thanks to the Moore family’s stakes in Nabisco, US Steel, Bankers Trust, and the American Can Company. But he was acutely embarrassed by his privilege as a boy and more concerned with the inner life. Even so, when he and Jenny married after his heroic service as a marine in World War II, no one could have imagined that this glossy couple, raised in mansions with stables and cared for by servants, would end up living in inner-city neighborhoods, raising nine children, and orchestrating an open-door ministry, while working diligently for racial equality, workers’ rights, and world peace.

Moore’s child’s-eye view of her tall, charming, and tirelessly crusading father and her beautiful, resourceful, and stoic mother, as well as of Paul’s ascension in the church on the tide of his good works, would have been material enough for a significant memoir. But Moore’s portrait of her parents was instigated by the staggering revelation of her father’s bisexuality and affairs with men. Suddenly, everything she thought she knew about her family (and herself) was cast in doubt.

Switching between a linear account of her parents’ lives, glimpses of her youth, and contemplation of the profound implications of her father’s late-in-life confession, Moore subjects each memory to scrutiny, endures unnerving conversations with her father’s intimates, and studies the family archive, especially her parents’ frank letters and her mother’s comprehensive scrapbooks, which combine the usual memorabilia with decades’ worth of newspaper and magazine coverage. Gradually, old conundrums begin to make sense, prime among them her mother’s unhappiness and insistence on having so many children. Moore, attesting to her feeling of diminishment with the arrival of each of her eight siblings, comes to recognize that her own bisexuality has been “inextricably tied up” with her father’s, and she gains fresh insight into her involvement with the women’s movement and her commitment to literature.

As Moore performs the calculus necessary for reconciling her father’s role as a prominent radical priest with his hidden life as a “sexual trickster,” she remembers him telling her long ago that “he believed that sexuality and religious feeling came from the same place in the psyche.” Perhaps his own “complicated erotic life” sensitized him to the anguish of others and impelled him to fight inequality in all forms. (In 1977, he even ordained the first openly lesbian Episcopal priest.) As for Moore, “understanding meant telling,” and telling for this writer is a high art indeed. The bishop’s firstborn has created a gracefully structured, psychologically incisive, and socially resonant inquiry into the mysteries of sexuality and love, family and self, altruism and survival.