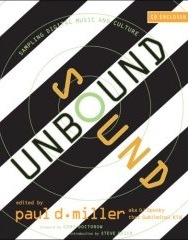

For a true music nerd, there is nothing more satisfying than listening to a piece of music, parsing out its samples, and hunting for the albums on which those sounds originally appeared. But while many fans view sampling as breathing new life into long-forgotten songs, others, of course, see it as infringement. Issues of appropriation—audio and otherwise—pervade Sound Unbound, a new anthology on digital music and culture edited by conceptual artist and musician Paul D. Miller (aka DJ Spooky that Subliminal Kid).

Miller’s first book, Rhythm Science (2004), presents a semiautobiographical manifesto on manipulating patterns in sound and culture to make art. Sound Unbound continues such critical-theory-rich themes. Featuring thirty-six essays, interviews, and artist statements on the concept of the remix, the collection boasts a roster of major avant-garde composers (Pierre Boulez, Brian Eno, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich), musicians (Scanner, Moby, Chuck D), critics (Simon Reynolds, Erik Davis), and tastemakers (such as Alex Steinweiss, inventor of the concept album cover). Articles on copyright law, Muzak’s pariahdom, hip-hop’s connection to Islam, and Raymond Scott’s early sequencers are interspersed with engaging first-person essays: Brian Eno offers a history of bell making and its relation to his current project, Clock of the Long Now, while his comrade in minimalism Steve Reich chronicles his own artistic output since the mid-’60s, revealing a lifelong ambivalence toward technology. A contribution by Scanner (aka Robin Rimbaud), who creates soundscapes using live mixing of police-radio and cell-phone signals, is a contemplative mix of memoir, artistic philosophy, and technical practice.

The book’s strongest entries are those by non–music critics. Novelist Jonathan Lethem’s wide-ranging essay “The Ecstasy of Influence,” first published in Harper’s last year, serves as the book’s keynote address on copyright and a clever exercise in employing “plagiarized” texts, from Bob Dylan to Lawrence Lessig to Lewis Hyde. In “The Life and Death of Media,” science-fiction writer Bruce Sterling contends that, due to the breakneck speed of today’s technological advancements, new-media art will ultimately, if not instantly, become ephemeral, since it will inevitably be part of a “dead operating system.” (“My PowerBook,” he explains, “has the lifespan of a hamster.”) Ironically, critic Simon Reynolds’s 1999 article on the renegade Cybernetic Culture Research Unit at Warwick University, with its references to “cyberpositivity” and techno-pagan culture, feels outdated. On the other hand, historian Catherine Corman’s essay on Joseph Cornell, examining the artist’s remarkably prescient manipulations of celluloid in his 1936 film, Rose Hobart, feels contemporary.

In true po-mo fashion, the essays in Sound Unbound are arranged in no particular order. (“To hell with your divisions and name descriptions!” Miller gleefully writes.) But as the book clocks in at nearly four hundred pages, such random organization makes reading a bit of a slog. Brief introductions or biographical information for the essays would have proved useful, as many beg for contextual grounding.

As with Rhythm Science’s companion CD, Miller has reached into Belgian label Sub Rosa’s archive of avant-garde and early electronic music. For Sound Unbound’s audio accompaniment, he offers a seamless mix of forty-five short tracks, juxtaposing recordings by Jean Cocteau, John Cage, and Marcel Duchamp with recent music by Ryoji Ikeda, Carsten Nicolai, and Sonic Youth, among others. In the role of DJ, Miller has added layers of crackles, strings, or funky beats to many of them (painfully so, in some instances).

Miller’s own writing can be both grandiose and puzzling. According to him, the book is “a plagiarist’s club for the famished souls of a geography of now-here.” But the eclectic range of Sound Unbound, if uneven, is admirable and should appeal not only to composers and musicians but also to artists, media theorists, anthropologists, computer geeks, and anyone interested in current debates on intellectual property.