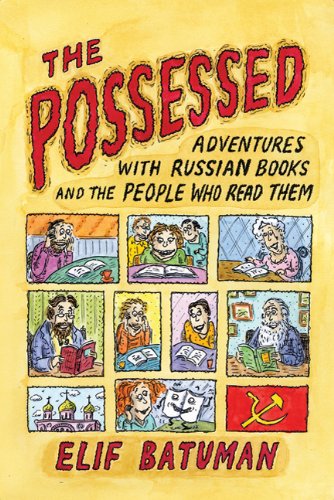

The most gifted essayists are often just brilliant storytellers. Such is the case with Elif Batuman in her debut collection, The Possessed. A teacher at Stanford University, she has published some of this work in the New Yorker, n+1, and Harper’s. Rather boldly for a tyro essayist, Batuman employs a first-person style, enriched with dialogue, characters, superb pacing, and sizzling rhetoric. It’s easy to imagine what a sharp and engaging lecturer she is—if, as her introduction has it, she has indeed “stopped believing that ‘theory’ had the power to ruin literature for anyone, or that it was possible to compromise something you loved by studying it.… Wasn’t the point of love that it made you want to learn more, to immerse yourself, to become possessed?”

Batuman is possessed, not only by Russian literature but by all the side streets, back alleys, and secret passageways she uncovers. She tries to find out whether Tolstoy was murdered; searches for Isaac Babel’s last living relatives, who are lost at San Francisco International Airport; and endures winter in Saint Petersburg to touch an ice palace with her own hands. Such escapades, anecdotes, and accidents sometimes don’t mix with her penchant for philosophical quandaries and literary theory. But Batuman’s classroom experience pays off here, as she mostly presents these weighty matters with humor, sensuality, and concision—framing ideas without condescension or jargon:

I am reminded of an anecdote about the folk hero Nasreddin Hoca. Walking along a deserted road one night, the story goes, Nasreddin Hoca noticed a troop of horsemen riding toward him. Filled with terror that they might rob him or conscript him into the army, Nasreddin leaped over a nearby wall and found himself in a graveyard. The horsemen, who were in fact ordinary travelers, were interested by this behavior, so they rode up to the wall and looked over to see Hoca lying motionless on the ground.

“Can we help you?” the travelers asked. “What are you doing here?”

“Well,” Nasreddin Hoca replied, “it’s more complicated than you think. You see, I’m here because of you; and you’re here because of me.” …

This story encapsulates the riddle of free will in human history: a realm where, as Friedrich Engels observed, free wills are constantly obstructing one another so that, inevitably, “what emerges is something that no one willed.” Nobody, least of all Nasreddin Hoca, willed for Nasreddin Hoca to end up lying in the graveyard that night. Nobody forced him there, either—yet there he was.

Within the first thirty pages of The Possessed, it becomes clear that meticulous, perhaps even obsessive research has gone into details that are consistent, and consistently gripping, throughout. But while some parts of the essays read like spy thrillers, others are more like episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm, with academics stealing one another’s parking spaces and then giving the finger. In one scene, Nathalie Babel (Isaac’s daughter) fixes her gaze on a professor across the dinner table and demands to know whether it’s true that the professor despises her, while the professor accused of despising stubbornly refuses to say that she does not.

Batuman writes not only for people who love Russian literature but also for those who didn’t know they do. Her descriptions of the working conditions of literary geniuses are so compelling that readers will feel affection for War and Peace even without having read it. Batuman couples a curiosity about the world with a respect for people, places, and their stories. This fresh worldview informs a critical approach that doesn’t rely on a smirk to sound savvy. Batuman at times piles on the telling details too thickly, suggesting that Babel’s “The Awakening” was the inspiration for King Kong. But readers quickly forgive such excessiveness as further evidence of her generosity and enthusiasm—a welcome contagion for her readers in the sterile realm of contemporary criticism.

Perhaps the collection’s most appealing characteristic is its beautifully turned prose. Good writing means knowing when to stop and let the reader enjoy the moment, and Batuman can demonstrate a sure hand on the brake: “[Dostoyevsky] made a three-day trip to the famous casino of Homburg, which in fact dragged on for ten days, during which he lost not only all his money but also his watch, so that afterward, he and his wife never knew what time it was.”

The Possessed reveals the riddles of genius in everyday experience and in common things, such as when the author describes Tolstoy’s fascination with the bicycle: “He took his first lesson exactly one month after the death of his and Sonya’s beloved youngest son. Both the bicycle and an introductory lesson were a gift from the Moscow Society of Velocipede-Lovers. One can only guess how Sonya felt, in her mourning, to see her husband teetering along the garden paths.” Batuman does what all great essayists do—she fills her readers with a passion for the subject at hand while simultaneously exploring its complexity.

Simon Van Booy’s story collection Love Begins in Winter (Harper Perennial, 2009) was awarded the International Frank O’Connor Prize.