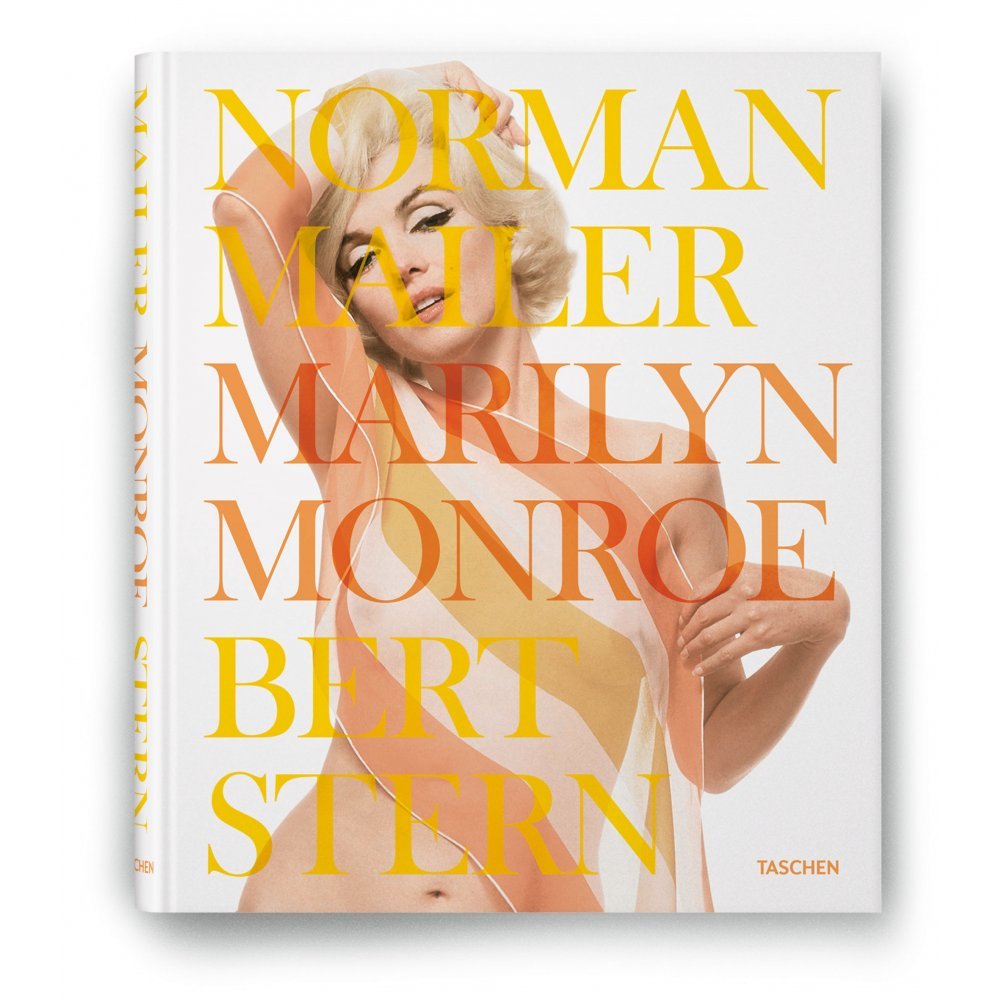

First, just let the product specifications sink in: Marilyn Monroe (Taschen), by Norman Mailer and Bert Stern, costs a thousand dollars. It pairs ninety-three thousand words Mailer wrote about Monroe in 1973 with more than a hundred shots from Stern’s 1962 four-day photo session with the doomed actress, snapped six weeks before her death.

Who would pay this kind of money for a glorified photo book? A person who wants to own a weighty, flashy object made specifically to call attention to itself (and to the tastes of the person who purchased it). And I must confess at the outset that I am not such a person—which means, in strict terms, I have nothing to say about the actual body in question. Taschen would not relinquish a review copy. So instead of sticking my nose in all of the book’s 278 fourteen-inch pages—which I assume are creamy and thick—and relishing the exclusive signed and numbered edition, I fingered a scroll button while images of a dead-eyed starlet stared back, sending creeps into my insides.

And in a way, that’s probably the most fitting way to take this curious project in. The whole thing gives off strenuously bad vibes. It’s not simply the offensive and vainglorious notion of a thousand-dollar art book—all but designed to set your teeth on edge with class resentment. No, it’s the actual insides of the book that are so distasteful. The Stern-Mailer collaboration originally came to light in a 1973 edition that paired Mailer’s Monroe appreciation with images of the starlet snapped by a host of different photographers. Here, however, Stern’s work takes center stage. Known as “The Last Sitting” (and recently re-created to still more macabre effect by Lindsay Lohan and photographers at New York magazine), the photos snapped at Stern’s studio have long been described as the most intimate and beautiful ever taken of Monroe. They are also exploitative, unflattering, and spooky.

Stern believed enough time had passed in Monroe’s career for her to shed her initial sexpot persona—she was studying with Strasberg now!—so he set out in a four-day photo session in a Bel Air hotel room to take an iconic, intimate picture of Monroe that would define her legacy.

Whether he succeeded depends largely on what you take Monroe’s legacy to be. After years of insomnia and poisonous pill popping, Monroe looks undeniably dazed in the majority of Stern’s pictures. You can instantly recognize what the cinematographer on John Huston’s set of The Misfits was talking about the day they finally halted shooting to allow Monroe a ten-day hospital visit for her various sicknesses: “Her eyes won’t focus.” Her sensuality flickers on some of the reprinted contact sheets, but so does her vulgarity. Inspecting these shots at close remove feels like you’re witnessing something obscene—a prelude to an autopsy. Maybe the photoset would be interesting on its own, as the crinkled skin around her eyes, the deep belly scar from a recent gallbladder surgery, and the wide thatch of pubic hair she playfully exposes all tell a story of the starlet’s wrestling (and restlessness) with her own sexuality.

But when the portraits are all juxtaposed with Norman Mailer’s muscular descriptions of the traumas of her childhood, the whole thing is just too brutal. Mailer relates how, by Monroe’s own admission, her grandmother tried to suffocate her with a pillow at two years old; he revisits the story of the crazed mother who left Norma Jean with neighbors while she convalesced for years in an insane asylum; and, of course, he re-creates, as only Mailer can, the constant sexual longing and humiliation that powerful men visited on Monroe throughout her life.

Here, for example, is Mailer’s matter-of-fact appraisal of her life in foster care: “At one foster home she sleeps in a closet without windows and is raped by the wealthiest boarder in the house, who invites her into his room.”

And here he is sizing up the impact of a failed pregnancy: “If few women are without depression after a miscarriage—they are dealing, finally, with a mystery, which for whatever reason, has chosen not to be born—then what of an avalanche of depression for Marilyn. The unspoken logic of suicide insists that an early death is better for the soul than slow extinction through a misery of deteriorating years.”

By 1973, when the text was originally published, Time magazine had featured both Monroe and Mailer on its cover. Mailer was by then considered the brutish head-butting monarch of American superjournalism—an obnoxious but impossible-to-ignore provocateur whose newest, most incendiary subject was his testosterone-heavy view of the women’s liberation movement. And in 1973, there was, of course, also the narrative lure of the previous decade’s long romance with the counterculture: In Mailer’s telling, Monroe and her barbiturate-induced death seemed to be a tragically suitable opening act to the ’60s—a harbinger of the decade’s fabled lost innocence, sexual tumult, and death trips.

And something of the trademark ’60s zeitgeist infused the Mailer project from the start. Lawrence Schiller—a magazine photographer infamous for snapping and releasing, with Marilyn’s blessing, the last Monroe photos in 1962, a set of pictures of the fully nude actress on the set of Something’s Got to Give—came up with the concept of the book: big, beautiful pictures of Marilyn next to provocative text.

Schiller’s publishers said that Mailer was his man. So Schiller contracted the writer to produce a thirty-thousand-word preface on quick turnaround for a collection of photographs of Marilyn taken by twenty-four different photographers.

Why did the fifty-year-old Mailer, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, forsake his obsessions with the key arenas of male glory—war, politics, the boxing ring—in favor of an art-book appreciation of the echt-feminine icon Marilyn Monroe?

“As a way of making money,” Mailer told Time magazine during the book’s initial launch.

“I’ve really gotten to the point where I’m like an old prizefighter,” Mailer said. “And if my manager comes up to me and says, ‘I’ve got you a tough fight with a good purse,’ I go into the ring. Nothing makes an old fighter any madder than to do a charity benefit.”

The thirty thousand words eventually ballooned into more than a hundred thousand and then into a slender biography, Marilyn: A Novel Biography. The text was printed alongside the work of two dozen photographers—including Stern, who had in the 1950s photographed Monroe as an athletic, apple-cheeked young magazine model; as a plump fledgling contract side player who couldn’t get a meeting with studio heads; and as the American angel of sex. The book sold for twenty bucks a pop and became an international best seller, though critics rolled their eyes at Mailer’s unheeding conjectures and unapologetic tumescence. “She looks fed on sexual candy,” Mailer writes of her breakout comedienne role. “Never again in her career will she look so sexually perfect as in 1953 making Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, no, never—if we are to examine a verb through its adverb—will she appear so fucky again.”

Though he had published the initial Monroe appreciation with plenty of now strange-reading, and occasionally sloppy, references to Nixon and the “Silent Majority,” Mailer was still, aesthetically speaking, a creature from his New York–in-the-’50s milieu. And so he treats his subject the way any modernist writer or artist would: by obliterating it. Mailer explodes Marilyn with the intensity of his own desires and fascination; he emolliates her, describing Monroe as sugar, honey, ice cream, and chocolate in the opening chapter. He swishes Monroe’s history in his mouth, ingests her, hides her in his bowels, then vomits her out. It is up to us to interpret the meaning of Mailer’s big splatters and streaks. You step back from the text of Marilyn, and it’s like you’ve been looking at a towering Rothko or Pollock; you’re haunted. The book gives the impression that you, through this dramatic exercise, know about Marilyn Monroe. Is it all The Truth? No, and Mailer is uninterested in Truth—so the joke’s on us if we’d come to this performance-art piece in search of facts.

Though Mailer’s techniques and intensity are all very high modern and unabashed, there is something positively grim in reading the new edition alongside the last pictures of Monroe. Mailer’s style may have been new, but the story’s overall downward plot trajectory is ancient. Mailer plays a latter-day Marquis de Sade—and Marilyn is his Justine.

She is, like Sade’s Justine, an intellectual naïf: half willful nymph to her sex, half unwitting somnambulist, alienated since childhood, constantly bending the gravity of her own sexual desire, while also punished by the brute lust of those around her, over and over. Since she’s incapable of learning from her own ordeals, Justine is forced to divulge her history before an open criminal court—just as Monroe is forced to account for every backseat grope, miscarriage, and spurned advance to the press. Finally, both heroines become depressed in their adult years and go to early graves as ciphers.

Yet there’s also the sensation that both Sade and Mailer delight in the exploits of their naïfs. They are fascinated, turned on, rubbing their ladybugs between their greedy thumbs and forefingers, leading up to the sad, ejaculatory moment when they bring the squeeze and she goes squish. You can feel it happening throughout the book.

No force from outside, nor any pain, has finally proved stronger than her power to weigh down upon herself. If she has possibly been strangled once, then suffocated again in the life of the orphanage, and lived to be stifled by the studio and choked by the rages of marriage, she has kept in reaction a total control over her life, which is perhaps to say that she chooses to be in control of her death, and out there somewhere in the attractions of that eternity she has heard singing in her ears from childhood, she takes the leap to leave the pain of one deadened soul for the hope of life in another, she says good-bye to that world she conquered and could not use.

Divorced from the morbid pictures, sold in a pulp paperback, the writing could be considered a recommended but nonessential work by Mailer. But the pairing of voyeuristic nipple studies and fantastical descriptions of trauma has all the intimacy and delight of a Pap smear. And really, who needs to fork over a thousand bucks for the literary equivalent of a diamond-studded speculum?

Natasha Vargas-Cooper is the author of Mad Men Unbuttoned: A Romp Through 1960s America (Harper Design, 2010).