In his chatty and astute new memoir, musician and super-producer Nile Rodgers recounts the inspiration for one of his most enduring songs. In 1979, he was in a crowded dive bar’s bathroom with a couple of Diana Ross impersonators when he wondered, “What would it be like if Diana celebrated her status among gay men in a song?” Rodgers, who was the core of the disco band Chic along with bassist Bernard Edwards, realized that the Motown diva could speak to her gay fans with a knowing wink—and the Ross classic “I’m Coming Out” was born.

As Rodgers narrates his story, anecdotes like this show that his signature talent is working as the perpetual underdog, finding artistic inspiration in unlikely places. He sneaks transgressive messages into smash radio singles, flourishes in improbable collaborations, and trades the spotlight for behind-the-scenes influence, reporting on pop music from the vantage of a prankish infiltrator. The position of chronic outsider came naturally to Rodgers, who survived a chaotic childhood with junkie parents in the ’50s, was a Black Panther in the ’60s, and made himself a disco legend with Chic in the ’70s. He had seen it all by the ’80s, when he wrote and produced a staggering number of hit songs for other artists in a cocaine-fueled blaze of studio work and clubbing.

During the 1979 “Disco Sucks” movement, Rodgers learned firsthand how pop careers are subject to fickle social and political forces. He describes the backlash as a “tale of elves, dragons, warriors, and monarchs” in which the white one-hit-wonder band the Knack was pitted against Chic to usurp “the dark rule of Disco (the music of blacks, gays, women, and Latinos).” Rodgers was still reeling from the music industry’s abrupt turn when he met David Bowie in a New York club in 1982—by then, Rodgers hadn’t had a hit since, he writes with a cringe, “way back in 1980.”

For Bowie, the Rodgers-produced album Let’s Dance (his best-selling record ever) was a pop exercise—the title track was Bowie’s “postmodern homage to the Isley Brothers’ ‘Twist and Shout.’” For Rodgers, the project was a chance to launch his comeback and to salvage the word dance from its toxic association with disco. He notes with his usual candor, “As a well-regarded white rocker, David had the freedom to use the word if he wanted.” He makes the point sharper when writing about Madonna’s 1984 album, Like a Virgin, one of the most successful albums in his accomplished roster: “Ironically, I was . . . the one with race-based theories about music. . . . I figured making hits with Madonna was going to be a piece of cake. . . . White people doing black music has always been a tried and true formula.”

Throughout his memoir, Rodgers makes writing chart-toppers sound easy, but as he describes his escapades and explains the “Deep Hidden Meaning” of his songs, we soon see the difficulties of the pop producer—his talent propels other artists to stardom while he remains relatively unknown. He doesn’t take it personally, though, as he vacations with the Material Girl, shops with Duran Duran, and speaks of everyone from Sister Sledge to INXS with regard. He excuses Bowie’s failure to credit him for Let’s Dance by writing that Bowie feared “the world was starting to overidentify him with this single album,” a phenomenon that Rodgers understands all too well: “To date ‘Le Freak’ is my biggest [hit song]—though not my favorite.”

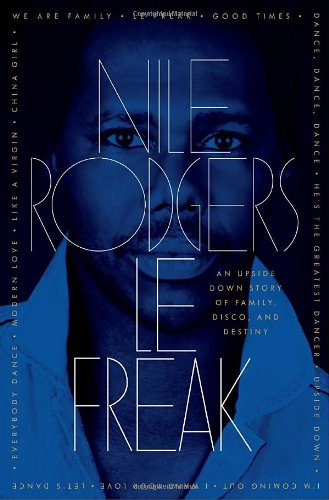

Nevertheless, Rodgers elected to title his memoir after his best-known song in a gesture worthy of a true pop impresario. It’s a fitting choice in more than the marketing sense, because like most songs in the Rodgers catalogue, “Le Freak” has a telling backstory: It was penned after he and Edwards were turned away at the door of Studio 54 (the hook, “Freak out,” was originally a “fuck off” directed at the club). Chic was able to parlay the sting of exclusion into a breakthrough single and the band’s first seven-figure check. As Rodgers muses on that pivotal experience: “By not getting what we wanted, we got more than we ever imagined.”