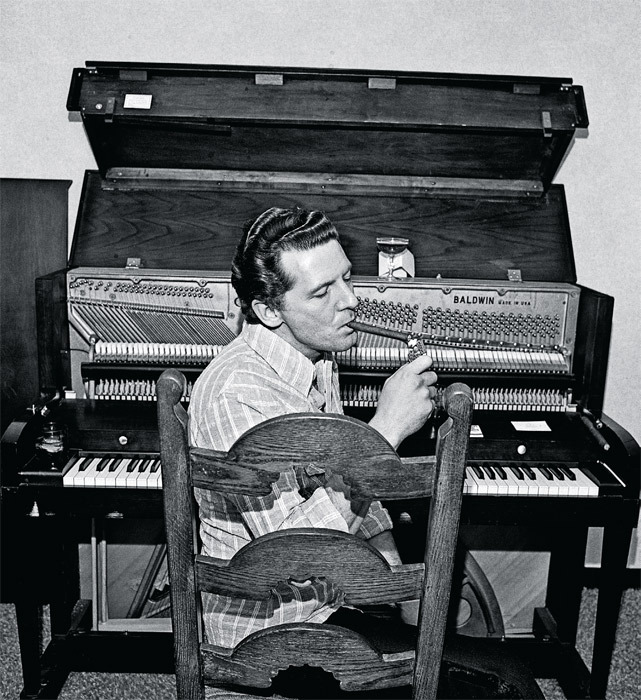

IF YOU DRIVE ACROSS the US or even anywhere outside the I-95 corridor, you discover that country music dominates the airwaves. New Mexico, Maine, or Montana—regardless of region, the radio twangs in tones redolent of Butcher Hollow, Kentucky. Country music is without a doubt this country’s music. Its cultural associations—the clothes, attitudes, and politics—also hold sway: Country style’s quixotic combination of the outlandish (rhinestones, tattoos, hard drinkin’, and bolo ties) with that old-time religion generates a paradoxical—but no less enjoyable—frisson. Sin and salvation have been combusting in hillbilly tunes for as long as the music’s been played; Kitty Wells probably expressed it best in her 1952 hit “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels.” That tension can be seen here in Henry Horenstein’s unembellished photographs of singers, guitarists, and fiddlers. Formally composed, these black-and-white images strike strong melancholic notes—he’s caught the pathos (and often bathos) that animates country lyrics. But the showbiz subjects of these restrained portraits are also shown as velour- and sideburn-sporting signifiers of flamboyant rebellion. Shot mostly in the ’70s, a period when country music was crossover dreaming, the photos document the fading of a down-home world in which the Grand Ole Opry, not Los Angeles, was the center. The music’s formative era is evoked in a snapshot-style image of Charlie Monroe (Bill’s older brother), a country-music originator, as he stands on his lawn, in white shoes and star-studded tie, wincing in the sunlight. Then there’s Jeannie C. Riley of “Harper Valley P.T.A.” fame posed in her plush-walled tour bus (two phones hang at the ready), wearing a pendant the size of a pancake around her neck and the obligatory cowboy hat. (Her big hit, like Wells’s a generation earlier, decried sexual double standards.) But the shot of Jerry Lee Lewis (above) best epitomizes the social and moral polarities at clamorous war in honky-tonk: The seven-times-married pianist (his third wife was his thirteen-year-old second cousin; number five died of a drug overdose; he’s also a cousin of disgraced televangelist Jimmy Swaggart) sits at an upright, wavy hair slicked back as he lights a long cigar with defiant aplomb. A onetime Bible-school student, Jerry Lee was expelled for playing a boogie-woogie version of a gospel hymn. It’s the devil’s music, he was told. And it may well be. But the devil has long ruled the airwaves in God’s country.