Earlier this year, I gave a speech in New York advocating female supremacy. At the end of it, I told the men in the audience to hand over all their cash to the women nearest to them. (My feeling is that this should be done on a global scale.) There wasn’t universal compliance, but some money did change hands. It was my first experience of activism, and boy, was it fun! So I can almost see how, once you get the bug, you can’t stop.

Gloria Steinem can’t stop, and that’s a great thing. She was the right person in the right places at the right times—flexible, modest, generous, indefatigable, and canny enough to weave her way past the ramparts of male power. She calls herself a “wandering organizer,” and this book has a wandery form of organization. Part memoir, part campaigning history, it mirrors Steinem’s own antipathy to hierarchy: Unhampered by chronology, its chapters are almost interchangeable. So, among her other achievements, Steinem has liberated the memoir form.

An inspiring political chronicle, My Life on the Road is illustrated by personal anecdotes and a few statistics, no doubt in the style of many a Steinem speech—which she will deliver pretty much anywhere, from subway stops, bagel shops, and backyard barbecues to school gyms, YWCAs, churches, bookstores, and college campuses. Much of it is concerned with the patient toil involved in getting bills passed, candidates selected and elected, consciousnesses raised, and enemies thwarted (Betty Friedan was one; the pope another). The writing can get personal, and moving, but she’s not going to dish the dirt on her love life, if that’s what you were hoping. She mentions merely a handsome boyfriend in high school, her engagement to “a good but wrong” man in college, a tryst in a taxi, and a misguided attempt to fund-raise one weekend in Palm Springs among her rich boyfriend’s rich pals, one of whom had a connection to Frank Sinatra. Steinem ruefully surveys Sinatra’s vast collection of miniature trains: “I try not to think about how much all this cost. . . . In three days of talk about how to make money, I haven’t been able to insert one idea about what to do with it.”

The book may lack the sparkle of her best journalism—like when she wrote in Ms. in 1978, “if men could menstruate . . . [they] would brag about how long and how much”—but My Life on the Road has its moments. There’s the time she gave a speech on Harvard Law School’s institutionalized sexism at a Harvard Law Review banquet, nearly reducing one professor to apoplexy. Writing an article in 1968 in defense of Ho Chi Minh, she needed to check a few facts, so she sent Ho a telegram (finding an address wasn’t easy), but he never got back to her—he must have been busy. She also reveals that around the time when they were all setting up the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) together, Betty Friedan threatened to sue because she hadn’t been reelected to an NWPC position and took to yelling at Steinem and Bella Abzug in public. Steinem, hating direct conflict, avoided Friedan, but Abzug once injured her vocal cords yelling back.

As well as cofounding New York and Ms. magazines, Steinem wrote about and participated in numerous presidential campaigns. She recalls Nixon’s embarrassing attempts to ingratiate himself with members of the press by lurching to the back of the plane and spouting some totally out-of-date personal detail about each reporter. Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern both disappointed her: McCarthy for his aloofness, and McGovern for his reluctance to openly support abortion rights. Robert Kennedy would have been better. People doubted whether Geraldine Ferraro could ever be “tough” enough to press the button, but “didn’t ask male candidates if they could be wise enough not to.” And the response to Hillary Clinton during her 2008 fight for the Democratic nomination was way beyond rude, with nutcrackers made in her image, T-shirts that said BROS BEFORE HOS, and about a million Rush Limbaugh banalities, from “Will this country want to actually watch a woman get older on a daily basis?” to his comparison of Clinton’s legs with Sarah Palin’s. (How about his legs?) “No wonder such misogyny was almost never named by the media,” Steinem comments. “It was the media.”

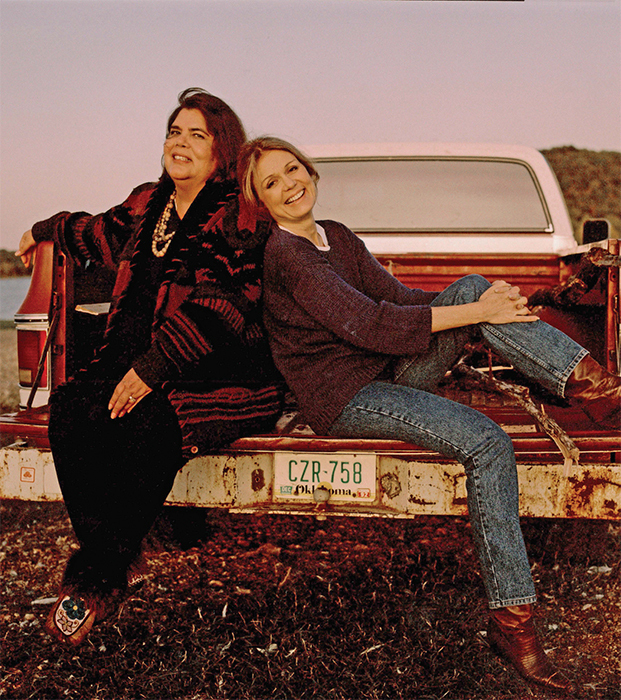

My Life on the Road traces the growth in Steinem’s thinking about sexual politics, from the initial it’s-not-fair stage, through her adoption of Gandhian tactics, to her fascination with the Iroquois Confederacy, “the oldest continuous democracy in the world.” Indeed, the real narrative that emerges here is Steinem’s increasing involvement with Native American culture and prehistory, a quest greatly aided by her friend Wilma Mankiller, the first woman ever to be elected chief of the Cherokee Nation. Steinem was stunned by the way Native American activists hold meetings: “It took me a while to realize, These men talk only when they have something to say. I almost fell off my chair.”

But the best character here is Steinem’s father, whose marriage proposal to her mother was “It will only take a minute.” His letterhead read, “It’s Steinemite!” He was continually on the move, driving across the country selling antiques to roadside stands. She recalls that his “idea of childrearing was to take me to whatever movie he wanted to see, however unsuitable; buy unlimited ice cream; let me sleep whenever and wherever I got tired; and wait in the car while I picked out my own clothes. . . . [T]his resulted in such satisfying purchases as . . . Easter shoes that came with a live rabbit.” Steinem didn’t go to school until she was ten, and learned to read by studying road signs, with their helpful illustrations of hot dogs and hotel beds. She was thus “spared the Dick and Jane limitations that school then put on girls.” But there’s a sense here that her mother, who’d been a newspaper reporter, sacrificed a career, an alternative romance, a life in New York, and her sanity in order to have children. Steinem has been “living out the unlived life of my mother” ever since—when she isn’t traveling, that is, like her father.

Steinem is hooked on travel, and urges us all to do more of it: It is a bit silly for women to stay at home when that’s where they’re statistically most likely to be murdered. For Steinem, travel has been a compensation, a compulsion, and a political tool. It’s the communal aspect of it she craves, not the glamour. She reviles the isolating effect of private cars and private jets, of taxis with window barriers that make her feel “as if I’m ordering French fries.” A whole chapter is devoted to taxi drivers she’s met, including a racist she had to ditch mid-journey, a vocal (female) advocate of tantric sex, and a guy who had decided to abjure all forms of media so as to live in the real world. “I’ve been clean for eight months,” he proudly reports.

My Life on the Road downplays the assault on the female psyche that was ’60s America, but there are glimpses of what Steinem endured as punishment for being smart, good-looking, ambitious, and angry. While coveringRobert Kennedy’s New York Senate race, she recalls sitting in a taxi between fellow writers Gay Talese and Saul Bellow. Steinem was mid-sentence when Talese leaned across her to inform Bellow: “You know how every year there’s a pretty girl who comes to New York and pretends to be a writer? Well, Gloria is this year’s pretty girl.” Steinem didn’t erupt (neither did Bellow), but she admits that it’s been trying to see her success continually attributed to her appearance.

One obstacle she faced in becoming an organizer was her dread of public speaking. She found a way around it by teaming up with partner speakers. These included Dorothy Pitman Hughes and Margaret Sloan, African American activists who brought with them a more diverse audience. It was a breakthrough for Steinem. Florynce Kennedy even tried to cure her of her statistics addiction by saying, “If you’re lying in the ditch with a truck on your ankle . . . you don’t send somebody to the library to find out how much the truck weighs. You get it off!” Kennedy’s counsel didn’t take—Steinem kept her journalist’s weakness for numbers, but she still became an engaging if not flamboyant speaker. A firm believer in the power of talking circles, she reports that her biggest thrill is when people in the audience start answering each other’s questions.

Early in her career, when she tried to get assignments to write about women, she was told that articles about equality would have to be balanced by ones in favor of inequality, for the sake of objectivity. Things have perhaps moved on. But Steinem is still stuck trying to convince people across the land that reproductive freedom is essential to gender equality. Curiously, she’s not in favor of matriarchy, and suggests it’s “a failure of the imagination” to have one group dominating another. Now, this I resent. To me, equality shows a lack of imagination. Sure, it might do, in a pinch, but female supremacy would be a lot more fun. Men are too keen on war, oil, money, beef, and golf. Only by restraining them can we hope to reverse the social and environmental damage done by patriarchy over the past five thousand years. And in this revolution, men can lick the envelopes and make the tea.

Lucy Ellmann is a novelist; her most recent work is Mimi (Bloomsbury, 2013).