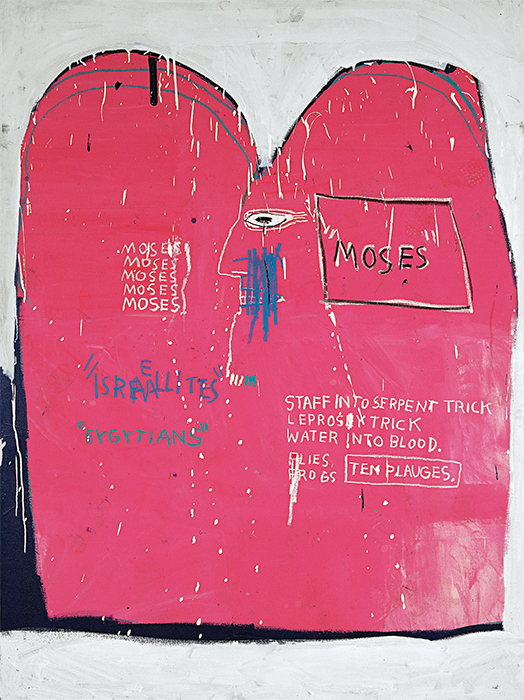

Even among the crew of language-besotted artists—Ed Ruscha, Barbara Kruger, John Baldessari, Marcel Broodthaers, Bruce Nauman—the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat stands out as especially devoted to words as subject matter. Indeed, enigmatic poems rather than images constituted his earliest forays as a graffiti artist (in a duo with the nom de plume SAMO©). But the move to canvas hardly diminished his affection for painted words, numbers, sentences, and names. In WORDS ARE ALL WE HAVE: PAINTINGS BY JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT (Hatje Cantz, $60), several critics survey the artist's language-based art, and a verse response from Thomas Sayers Ellis enacts a conversation between two poets. Basquiat employed William S. Burroughs's "cut-up" technique with found texts to create complex arrays of cryptic phrases, runelike signage, and repetitive lists. Crossed-out words and misspellings reinforce the paintings' improvisatory mood, the sense that the artist is thinking with his brush. The depiction of words emphasizes their visual materiality, even as it intensifies their literariness; riddles so evidently made by hand become even more tantalizingly ambiguous. Moses and the Egyptians, a canvas from 1982, presents Moses's tablets sans the Ten Commandments. Instead, we read the prophet's name and a partial account of his accomplishments ("STAFF INTO SERPENT TRICK," "WATER INTO BLOOD"): The "billboard" space otherwise reserved for the word of God is tagged with a boastful graffito. From the beginning of his career, Basquiat's words were always alive to context and, consequently, to their potential for subversion. —Albert Mobilio

FOUR GENERATIONS: THE JOYNER/GIUFFRIDA COLLECTION OF ABSTRACT ART (Gregory R. Miller, $55) surveys one of the foremost assemblies of African American and African-diasporic art, with work spanning the modern and contemporary eras. Artists include Mark Bradford, Lorna Simpson, Norman Lewis, Glenn Ligon, Jennie C. Jones, and Julie Mehretu. The book's cross-generational approach illuminates intriguing connections: Bradford's 2012 mixed-media collage on canvas Lead Belly, with its jagged blue and white lines puncturing a black background, can be understood as part of a lineage including Norman Lewis's 1947 work Magenta Haze. If at first these links seem tentative, or merely instances of loose affinity, editor and contributor Courtney J. Martin deftly dispels that impression. Through essays, reproductions, and interviews, Martin convincingly presents a genealogy of African American artistic production over the past seventy years. In one of the book's many enlightening moments, a conversation with Bradford and Charles Gaines, the latter artist mentions that, in a class he taught at CalArts (Valencia, CA), he aimed "to fill [a] gap by presenting the history of black practices within a larger context of modernism." By bringing together the disparate efforts of an impressive range of artists, curators, and scholars, this compendium goes a long way toward achieving that goal, upsetting the reductive narratives and false dichotomies that so often accompany work by black artists. —Andrianna Campbell

Fairfield Porter is Pierre Bonnard's heir to the messy-dining-table-as-painting tour de force, demonstrating, as he put it, "respect for things as they are." We love Porter for his depiction of a very particular vein of postwar New England Americana. It's a little (or, as we now know thanks to Justin Spring, a lot) bohemian, crowded with children, artist and poet friends, speckled lawns, gray oceans, and screen porches surrounded by hawkweed. Here it would be perfectly natural to stumble on a breakfast scene in which Porter's patient daughter sits alone at a table, flowers spilling onto her high chair, a jar of mustard next to a book of Wallace Stevens's poetry (his wife, Anne, was quietly an accomplished poet). FAIRFIELD PORTER: SELECTED MASTERWORKS (Rizzoli, $65), with essays by John Wilmerding and Karen Wilkin and a poem by J. D. McClatchy, features color-steeped reproductions (150, in fact) of landscapes, still lifes, portraits from Maine and the East End of Long Island, and the rare New York City shot. By turns awkward and graceful, these images dodge nostalgia but not the aching pleasure found in, among other things, the clotted light of a bunch of buttercups. —Prudence Peiffer

Produced on the occasion of her retrospective at the Queens Museum of Art, MIERLE LADERMAN UKELES: MAINTENANCE ART (Prestel, $75) unpacks the septuagenarian's extensive use of affective labor (i.e., "care work") as a form of social-practice art avant la lettre. This 256-page catalogue of her feminist output—from washing the sidewalks in front of a gallery in 1974 to becoming the first artist-in-residence at the City of New York Department of Sanitation (DSNY) in 1977, to several more decades of dealing with trash—features insightful essays by Larissa Harris, Lucy R. Lippard, and Patricia C. Phillips. But what makes the volume sparkle are Tom Finkelpearl's interviews with four DSNY commissioners who worked with Ukeles, which together provide a minihistory of the city, as well as a section devoted to the artist's writings. In 1969, Ukeles asked, "After the revolution, who's going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?" The question remains unanswered.

One of the virtues of art historian Anastasia Aukeman's highly anticipated book WELCOME TO PAINTERLAND: BRUCE CONNER AND THE RAT BASTARD PROTECTIVE ASSOCIATION (University of California Press, $50) is its focus on a distinctive mode of postwar artmaking in California: neo-Dada assemblage, or "junk" and "funk," per some derisive critics of the 1950s and '60s. A fluctuating group of poets and artists including Conner, Jay DeFeo, George Herms, Wallace Berman, Jess (Burgess Collins), and Manuel Neri, among others, worked for over fifteen years at 2322 Fillmore Street in San Francisco. Dubbed "Painterland," the building was the base of operations for this proto-punk posse, who were driven to produce despite naive criticisms of their art. Sedulously linking their varied works to an outsider ethos that resisted prevailing American consumer culture, Aukeman's book is a fascinating history of that far-out and foundational era. Reflecting on her shabby sculpture Fur Rat, 1961, a tribute to her Rat Bastard membership, the still-too-little-celebrated artist Joan Brown reminisced: "The rat is an ominous creature, one that most people will do anything to avoid. And here [we] almost glamorize it. We were all so young." —Lauren O'Neill-Butler

Tucked into the back pages of Nan Goldin's latest volume, DIVING FOR PEARLS (Steidl, $45), are three of Fosco Maraini's sumptuous photographs of Japanese Ama pearl divers from 1954. The images depict the women's work at its most elegant, capturing the seemingly effortless glide of the dive, rather than the brutal business of prying open oysters or the exasperation of an empty shell. In the accompanying text, Goldin uses this occupation as a metaphor for her own, likening "good pictures" to the elusive pearl. Diving for Pearls collects over 165 of the artist's recent images (most previously unpublished), alongside essays by Glenn O'Brien and Lotte Dinse. Like Maraini's pictures (or, for that matter, a string of pearls), Goldin's photographs leave their labor largely invisible, enacting a kind of magic that belies the mechanics of their making. The book opens with a strand of loose equivalents, pairing Goldin's casual portraits with excerpts of paintings by the likes of Lucas Cranach and Claude Vignon. The gesture places Goldin's offhand shots into a larger art-historical narrative, while inflecting the Old Masters with the brittleness, spontaneity, and blistering intimacy that have become the photographer's calling card.

Taryn Simon has built a practice photographing that which is not intended to be seen, from confiscated contraband goods to living individuals who, for one reason or another, have been legally declared dead. With PAPERWORK, AND THE WILL OF CAPITAL (Hatje Cantz, $100), the artist turns to an explicitly conspicuous subject—the flower arrangements decorating signings of major international economic and political agreements—as a way to trace the invisible networks these bouquets represent. Simon painstakingly researches and restages past arrangements, from the hydrangeas that marked the 2012 contract to build a Park Hyatt in St. Kitts, to the date palms at a 1994 Marrakech conference on intellectual-property rights, to the staid combination of carnations, asters, and chrysanthemums accompanying the signing of the Maastricht Treaty. After photographing each bouquet, Simon presses and photographs individual stems. The images appear here in multiple configurations, alongside either printed descriptions or historical photos of the events they commemorate. Lap-size and leather-bound, the book itself handles like an encyclopedia, with texts by Kate Fowle, Nicholas Kulish, and Hanan al-Shaykh. As an additional touch, a glossary compiled by botanist Daniel Atha cross-indexes each plant and its characteristics with the signings at which it appeared, creating a floriographic lexicon of modern capitalism. —Kate Sutton

The eminent historian Kenneth Frampton has spent nearly half a century unpacking the social, cultural, and political implications of architecture's physical dimensions, and his latest book, A GENEALOGY OF MODERN ARCHITECTURE (Lars Müller, $40), outlines a method for reading buildings as articulations of a fully material and spatial language. Deploying what he calls a "comparative critical analysis," Frampton examines fourteen pairs of buildings (each pair comprising buildings erected to serve a similar purpose at a similar time), relying primarily on a series of rigorous and information-rich plan and section drawings prepared specifically for this volume. At their best, these comparisons are nothing short of revelatory, as when Frampton reads the Finnish Pavilion constructed by Alvar Aalto for the 1937 Paris World Exhibition against the Pavilion des Temps Nouveaux, constructed by Le Corbusier for the same occasion. Here, in the contrast between Aalto's intimately scaled, timber-framed volumes and the open plan of Le Corbusier's lightweight, cable-stayed structure, Frampton sees two fundamentally different visions of modern collectivity: one based on the embrace of new technology and the dream of a universal democratic space, the other grounded in vernacular building traditions and the more intimate encounters produced by small-scale social networks. In A Genealogy, architecture emerges as an agent rather than a symptom, with the ability to not merely reflect, but actually shape, social relations and cultural thought.

If Frampton's analysis starts with built form and turns outward toward architecture's broader cultural significance, engineer Guy Nordenson looks inward, decoding the form's underlying structural logic. In READING STRUCTURES: 39 PROJECTS AND BUILT WORKS (Lars Müller, $60), Nordenson offers an engagingly personal and unabashedly technical account of three decades of practice. There is a poignant paradox at the center of Nordenson's narrative. When his art is realized in its most sophisticated form, it is often invisible, delivering what he terms "the judicious disappearance of structure," a phrase he uses to describe his work with Yoshio Taniguchi on the Museum of Modern Art in New York's 2004 expansion. In order to provide an unobstructed expanse for the museum's main contemporary gallery, he removed two columns and hung the floors overhead from a massive truss buried within the walls above. This ingenious structural solution becomes visible to Nordenson's readers only through the book's detailed diagrams. Indeed, Nordenson's approach relies on revealing what is typically hidden or overlooked, primarily through the book's many elegant drawings (supplemented online by a library of digital models). The fact that this engineering sleight of hand—a gallery in which the ceiling hovers over the floor—is rarely noticed by visitors is arguably what makes it so effective. But it is this tendency to inhabit buildings without really looking at them that also leads us to forget what Frampton calls architecture's "potential to resist"—the stubborn and specific materiality that makes the practice particularly important in our overcommercialized and hypermediated age. Frampton and Nordenson remind us that, now more than ever, architecture deserves a closer look. —Julian Rose

In BRUCE CONNER: IT'S ALL TRUE (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/University of California Press, $75), the artist embodies a one-man San Francisco scene: beatnik partyer, political prankster, punk thrasher, spelunker of the inner cosmos, and, when it suited him, canny exploiter of art institutions. Or, as Peter Boswell, the lead author of the Walker Art Center's 1999 catalogue 2000 BC: The Bruce Conner Story Part II, puts it, "Taken together, his work looks like a one-man group show." The virtues of Bruce Conner: It's All True include an extensive biographical narrative by Rachel Federman and the inclusion of Conner's very late work (the artist "retired" in 1999, but continued to make work until he died in 2008). But it's missing a succinct critical frame for the artist's hard-to-grasp output—encompassing assemblage, collage, drawings, installations, and his found-footage films, which are the highlight of his surviving oeuvre. Necessarily omitting films and their hypnotic audio, the book still offers collages that are like little pictorial jewel boxes, full of almost indiscernible details, and the inkblot drawings Conner made late in his career, whose nearly microscopic Rorschach figures can induce a practically hallucinatory visual immersion. —Christopher Lyon

One never gets the sense that the photographs in Alex Webb's LA CALLE (Aperture, $60), a collection of streetscapes taken in Mexico between 1975 and 2007, were thought out much in advance. The pictures here present hectic (or eerily still) scenes in medias res, in which something has just happened, or is perhaps about to happen. Webb thrives on this uncertainty, creating compositions that give the impression that he has just shown up, and is in the process of trying to figure the situation out. The viewer, too, strives to piece together the overload of information: When looking at these brightly colored photographs, it can be difficult to settle on a focal point, or to see how the seemingly unrelated story lines interact. A single shot may show vendors, lovers, a bicyclist, children playing, and dogs. The mood can be tough to pin down, too, as people's faces register wildly different emotions, ranging from laughter to fear to tears. While each photo here looks curiously at the collective action it presents, the volume as a whole concerns itself with even more far-reaching connections. As Webb asks: What is the relationship between these portraits, one of which shows a man who appears to have been shot in the street, and the baroque drug violence that has erupted in the country? Webb resists definite answers, but his images suggest, in addition to a celebration of life on the street, a certain volatility—homelessness, poverty, and areas hemmed in by walls. One photo captures a foot blurring in movement as its owner disappears over a fence. True to form, Webb leaves us wondering what is being fled, and whether this was a successful escape. —Michael Miller