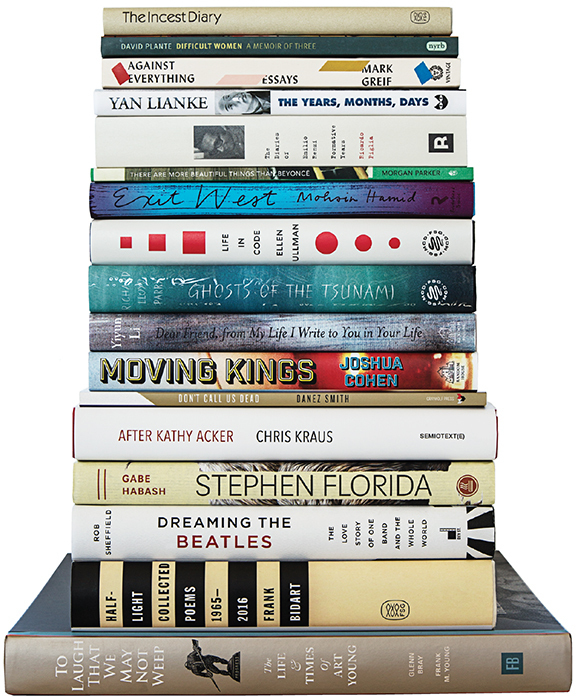

The old questions about literature’s necessity in dark times received a new hearing in 2017, and the affirmative case seemed, some feared, a bit harder to make. Who could settle in with a book while the president was probably starting a war on Twitter? And yet it’s apparent that books have remained essential as conversation starters, escape vehicles, and signs pointing to new ways of thinking and living. We asked writers to name their favorite books of the year, a query that resulted in the list presented here—unscientific, informal, and blessedly free of the T-word.

BACK IN MAY, I said (i.e., tweeted) that Gabe Habash’s debut, Stephen Florida (Coffee House, $25), was “my favorite novel I’ve read so far in 2017”; now that the year is over I’ll say it again sans qualifier. Stephen Florida is relentlessly inventive, utterly unyielding to expectation, and there’s not a dull line in the thing. I read it in a daylong frenzy of pleasure and envy, and it has been seared into my mind ever since. —Justin Taylor

IN A YEAR WHEN fiction felt, at best, irrelevant, the two novels that stayed with me for the moral force and grandeur of the political imagination behind them were Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West (Riverhead, $26) and Joshua Cohen’s Moving Kings (Random House, $26). As for nonfiction, I was profoundly moved by Richard Lloyd Parry’s account of one Japanese primary school’s preventable destruction by the catastrophic 2011 Tohoku tsunami, Ghosts of the Tsunami: Death and Life in Japan’s Disaster Zone (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27); I was impressed by the ethnographic rigor and care of Rachel Sherman’s Uneasy Street: The Anxieties of Affluence (Princeton University Press, $30); and I always love Ellen Ullman’s essays, collected this year in Life in Code: A Personal History of Technology (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27). —Gideon Lewis-Kraus

THE YEARS, MONTHS, DAYS, by Yan Lianke (Black Cat, $16), consists of two novellas. I like the first one, but the second, Marrow, is astonishingly good. It is filled with a deep melancholy mixed with a ghostly comedy and a rare sort of narrative energy. Utterly unpredictable and brilliantly weird. —Colm Tóibín

DIFFICULT WOMEN: A MEMOIR OF THREE (New York Review Books, $17), David Plante’s memoir about befriending famous women, was recently reissued. Only the paper is acid-free. The author is as openly sycophantic as Salinger’s Buddy but not such a drip. Jean Rhys is so drunk as to seem heroically so (she gets stuck in her toilet bowl); Sonia Orwell is self-importantly dramatic (the helpful crone); Germaine Greer is magnificently virile (but has ugly feet). I like a mean little book. In that vein, I also recommend Scott McClanahan’s The Sarah Book (Tyrant Books, $17). Though not as high-minded or elegantly turned out, it’s equally unforgiving and enviably immoral. —Kaitlin Phillips

ONE OF MY FAVORITE BOOKS from 2017 is the reprint of Difficult Women, by David Plante. Though some reviewers found Plante’s book “morally indefensible,” the objection sounds more like a veiled judgment of his subjects. Plante describes Jean Rhys, Sonia Orwell, and Germaine Greer lovingly, without condemnation. He is extremely precise in his depictions of these women, whose friendship he mysteriously craves. Meanwhile, he reflects on how pure his motivation to befriend them can be, given that he is an aspiring writer and they have connections and fame. It’s funny, original, and risky, and it concludes with an index comparing the three subjects on such matters as abortion, alcohol, and animals; an amusingly absurd end. (Also brilliant: Frederick Crews’s Freud: The Making of an Illusion.) —Sheila Heti

THE BEST NONFICTION BOOK I read in the past year was Ghost of the Innocent Man: A True Story of Trial and Redemption (Little, Brown, $27), by Benjamin Rachlin. —Richard Ford

MARK GREIF’S Against Everything: On Dishonest Times (Verso, $17), which came out in paperback this fall, stays with me as one of the more thought-provoking books of the year. Greif’s voice is intensely engaged, whether he is discussing the culture of pedophilia or his favorite rock band. Although he occasionally swerves into academic jargon, Greif mostly steers clear of the usual pieties. He writes as if writing well and thinking hard still mattered. —Daphne Merkin

ONE VIVID MOMENT of my year in literature was seeing Morgan Parker read her poem “ALL THEY WANT IS MY MONEY MY PUSSY MY BLOOD.” The poem starts, “I am free with the following conditions / Give it up gimme gimme.” Parker read outside at a podium in Portland, Oregon: chlorophyll, gliding mallards; money, pussy, blood. It’s a poem that punctures the cruel optimism of savings accounts, Black History Month, student loans. Its narrator teeters between obedience and avidity. “I do whatever I want because I could die any minute. / I don’t mean YOLO I mean they are hunting me,” she read. But also: “I do everything right just in case.” It’s from a collection called There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé (Tin House Books, $15). —Emily Witt

AFTER KATHY ACKER: A LITERARY BIOGRAPHY (Semiotext(e), $25), by Chris Kraus, gave me my favorite reading experience of the year. I’ve been obsessed with Acker for ages, but I’ve never been so hooked on the details of her life. It’s a sparkling, meticulous, intelligent, and well-rounded biography that everyone should read. Even nonfans will be mesmerized, in spite of themselves! I must also mention Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead, which may be the greatest book—not just of poetry, but of any writing, period—I’ve read all decade. —Porochista Khakpour

FOR THE PAST FEW YEARS, every Latin American novelist I know has been telling me how lavish, how grand, how transformative was the Argentinean novelist Ricardo Piglia’s final project, a fictional journal in three volumes, Los diarios de Emilio Renzi—Renzi being Piglia’s fictional alter ego. And now here at last is the first volume in English, The Diaries of Emilio Renzi: Formative Years (Restless Books, $20), translated by Robert Croll. It’s something to be celebrated, just as we should celebrate the translation of another vast Argentinean bildungsroman of reading and writing, Rodrigo Fresán’s The Invented Part (Open Letter, $19), translated by Will Vanderhyden. Both novels offer one form of resistance to encroaching fascism: style. —Adam Thirlwell

FRANK BIDART’S Half-light: Collected Poems 1965–2016 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $40) comprises fifty years' worth of daring, revelatory poems. For me, it’s the book not just of the year but of the decade. The most remarkable new book of prose I read in 2017 was Yiyun Li’s Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life (Random House, $27), which may be the most beautiful book I’ve ever encountered about what it means to devote one’s life to literature. —Garth Greenwell

MY FAVORITE BOOK OF 2017 was my own, Moving Kings. Because I worked very hard on it. Because it’s good. Because if you can’t be proud of your own achievements, bought at the cost of health and youth and sanity, what’s the point? —Joshua Cohen

AS MUCH MONUMENT AS COMPENDIUM, the hefty, cleanly designed volume To Laugh That We May Not Weep: The Life & Times of Art Young (Fantagraphics, $50) enshrines, even as it comments on, the work of the preeminent American political cartoonist—the equal of Thomas Nast—who was also a socialist. A humorist who moved left in his forties and never looked back, Young (1866–1943) was most closely associated with The Masses and was tried for sedition along with its editor, Max Eastman, but he drew for a number of publications, including his own, Good Morning. Young’s antiplutocrat, anticlerical, beautifully drawn cartoons are still fresh and as powerful as any tabloid front page. Among other things, the book documents a history that we might usefully revisit. —J. Hoberman

IN A BARE MINIMUM OF SPARE, straightforward pages, the anonymous author of The Incest Diary (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $18) manages to accomplish a nearly inconceivable literary task: She makes it possible not only to imagine the psychological impact of ongoing sexual violation but also to understand in visceral terms why she and so many others cannot escape their abusers. Some people have dismissed this book by calling it “porny” or exploitative; this might be because reckoning with the way all women’s sexualities are shaped by the structural dominance of men is profoundly uncomfortable. The author is such a brilliant writer, though, that there are moments of joy and beauty to be found even within that discomfort; perhaps the discomfort even makes them sharper and more precious. —Emily Gould

MY VENN-DIAGRAM BOOK of the year was Rob Sheffield’s Dreaming the Beatles: The Love Story of One Band and the Whole World (Dey Street Books, $25), a book about my favorite band, by my favorite music writer. Though the chapters are roughly chronological, Sheffield makes each one pop with a combination of next-level theorizing, charming personal history—“Am I a Red Album kid (1962–1966) or a Blue Album kid (1967–1970)?”—and a gift for starting the argument you hadn’t thought of. To wit, is “I Saw Her Standing There” the “best first song on a debut album, ever”? (Sheffield says yes, then happily lists a dozen other contenders, from N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” to the Smiths’ “Reel Around the Fountain.”) In the ’90s, was the band’s postcareer “drop-T” logo “a brand as powerful (in a different way) as the Black Flag bars”? (No, right? Or . . . maybe? Or . . . yeah!?) He’s brilliant at finding meaning in the seemingly trivial; for some reason I choked up on page 107, when Sheffield not only casts a kindly eye on what were my own humble introductions into the mysteries of Beatledom—1981’s “Stars on 45 Medley” (which I taped off the radio before I had a single Beatles album) and 1982’s Reel Music (a selection of their film-related songs; my aforementioned first Beatles album)—but even makes sense of these materials. The whole book pulses with joy and makes for a sunnier (but no less thrilling) counterpart to another wonderful book about dreaming the Beatles, Devin McKinney’s 2004 Magic Circles. —Ed Park