IN TATYANA TOLSTAYA’S EARLIER SHORT-STORY COLLECTION, White Walls, a character remarks, “If a person is dead, that’s for a long time; if he’s stupid, that’s forever.”

This was marvelous, I thought, one of those wise, wise Russian sayings.

I mentioned this to a friend.

“Oh that’s all over the internet,” she said.

“Really?” That was disappointing.

She produced her device and paddled her finger across it like people do and said, “See? Here.”

“When you’re dead you don’t know that you’re dead, and it’s the same when you’re stupid,” the screen reported.

“But that’s entirely different,” I protested. “That’s not the same at all!”

“Well your Russian one doesn’t make any sense,” my friend said.

Which is so untrue, so distressingly untrue. The American aphorism is dogged and stolid, the Russian one bright and playful. Besides, everyone knows that being dead does go on for a long while.

In another story, Tolstaya mentions three characteristics of the Russian personality—boldness, a seemingly inexhaustible ability to bear sorrows patiently, and an attitude of “Let’s hope.” “If those three things come together, you have ‘the Russian people’; if not . . . no ‘Russian people’ for you.”

Russians, she maintains, want grace, even when they don’t deserve it. Particularly when they don’t deserve it. They expect grace because they know God enjoys bestowing it. God says: “You, human, are a foul and drunken swine; I, in My inexpressible mercy, will shower you with the earthly comforts you desire—forget-me-nots, loose women, dough, booze, and chicken pot pie—all out of turn. For that is My whim.”

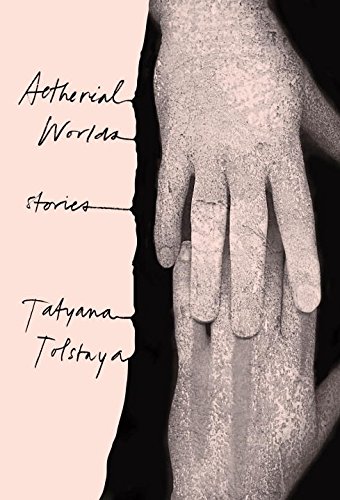

I came to the work of Tatyana Tolstaya (whose books The Slynx and White Walls are published by New York Review Books) through the brilliant translations of Jamey Gambrell, who has also given us the worlds of Vladimir Sorokin (Ice Trilogy, The Blizzard) and the diarist Marina Tsvetaeva. (The stories of Aetherial Worlds are translated by Anya Migdal.)

Aetherial is something of an odd word, though it’s just the obsolete form of ethereal, which as a signifier is bordering on the obsolete itself in these rapacious times. So you have a double sense of goneness in these stories, a ghostliness that is not so much tragic as grimly hilarious. The aetherial being in the title story is the protecting angel. Very reassuring. Everyone has one. For example, your love has dumped you, your feelings are hurt. “Your feelings—you let them out for a walk and they come crawling back to you, all bruises and missing teeth. Yes, yes, he’ll agree, that’s how it is. And also people die, but that’s just nonsense, isn’t it? They can’t just disappear, can they, they still exist, you just can’t see them, right? They must be up there, with you? Yes, yes, they’re here, all here, no one’s disappeared, no one’s been lost, everyone is well.”

You couldn’t ask for a better, more comforting companion. But everyone has a demon, too. And when the demon is in charge havoc ensues to a degree more twisted than usual, and there is nothing to do but drift, wait, and obey.

The aetherial, the demonic, and time, which crushes and falsifies and absolves all things, are Tolstaya’s subjects and the means by which she reveals and revels in the Russian character. Everything in this generous writer’s hands is vivid and alive. Here is a wolf (a Russian wolf of course):

It comes out on a hill in its rough wool coat smelling of juniper and blood, wildness, disaster, gazes grimly and with disgust at the blind windy vistas, clumps of snow hardening between its cracked claws, and its teeth are gritted in sadness, and a cold tear hangs like a stinking bead on the furry cheek, and everyone is the enemy and everyone is the killer.

And kombucha:

Where there is a kitchen, there is kombucha; where there is kombucha, there is caring, loving, nourishment, and anxiety. . . . It was like another child in our family—seven of us, plus Kombucha. Us kids, who were blessed to be born with legs and arms, with eyes—and him, prematurely born, eyeless, unable to move, let alone crawl. Yet he was alive. And he was ours.

And here, her alarming and extraordinary riff on aspic, the fearsome creation of aspic—first the trudge to the butcher’s on one of the shortest and most brutal days of December, then the purchase of the cow’s knees or pieces of the muzzle, lips, and nostrils. Or perhaps baby-pig feet with hooves.

None of them are really dead: that’s the conundrum. There is no death. They are hacked apart, mutilated . . . they’ve been killed but they are not dead. They know that you’ve come for them. . . . At home, you wash them and throw them into the pot. You set the burner on high. Now it’s boiling, raging. Now the surface is coated with gray, dirty ripples: all that’s bad, all that’s weighty, all that’s fearful, all that suffered, darted and tried to break loose, oinked and mooed, couldn’t understand, resisted, and gasped for breath—all of it turns to muck. All the pain and all the death are gone, congealed into repugnant fluffy felt. Finito. Placidity, forgiveness.

Tolstaya is divinely quotable—slangy, indignant, lyrical, crude. She picks you up—you’re light as a feather—and carries you along. You’re blown this way and that, cuddled and cast down, mocked and treasured. You don’t know where you’re going. None of it makes a lick of sense. It’s all detritus. It’s all sublime. The important becomes unimportant. The unimportant becomes . . . something else. Aunty Lola’s “personal cup—the one she drank her tea from and forbade us to touch—now idled in the sideboard; now you could just take it, but no one wanted to anymore.”

Rooms in an old dacha are damp but “thick with the wonderful scent of stale linen tablecloths.”

A hospital is “white and starched,” a place of “roses and tears and chocolates, and a blue corpse rolled swiftly down endless corridors followed by a hurrying sorrowing little angel clutching to its pigeon chest a long-suffering, released soul, diapered like a doll.”

Old man Dobroklonsky has four dachshunds. They have to be called in a precise order: “Myshka, Manishka, Murashka, Manzhet!”

But the old man is gone, the dachshunds are gone. But not really. Death has come but not completely, not hopelessly after all, for death in these stories does not really exist. No big whoop there. There is memory. Forgiveness. In an earlier story, the coldly perfect “On the Golden Porch,” childhood is recalled, consumed, discarded. Meek but frightening Uncle Pasha gets rid of the dacha’s yellow dog by stuffing him in a trunk filled with mothballs. Uncle Pasha grows old, the yellow dog climbs out of the trunk and embraces him. When the enfeebled man falls facedown in the snow and freezes to death on his own porch, the yellow dog “gently closed his eyes and left through the snowflakes up the starry ladder to the black heights, carrying away the trembling living flame.”

Lovely, right? But Uncle Pasha’s ashes end up in a metal can on a shelf in an empty chicken house because “it was too much trouble to bury him.” And he is forgotten, forgotten, forgotten.

This is Tatyana Tolstaya, the swerve and cackle, the breeziness and dark depths, the whoosh of time passing, the torrents of language and the offhand perfect touch—the dust on the road that falls like flour, the two lovely bream, mother and daughter, in the fishmonger’s window, the three-square-meter living space in a communal apartment.

She has been compared to Chekhov. Absurd: Chekhov, that sorrowful physician, that delicate ironist. Tolstaya barrels by him and knocks him in the ditch. Could Chekhov have written The Slynx, her novel about a post-nuclear-blast Russia where people eat mice and use them as currency, fear books (though treasure the sayings of Pushkin: “Life, you’re but a mouse’s scurry, why do you trouble me?”), won’t touch honey because it’s bee shit, are startled by chicken eggs (“Lord save us!—there was a yellow ball that looked like it was floating in thick water”), and blame their lack of reasoning skills on the Slynx, a howling, snappish creature that lives in the forest?

Could Chekhov have managed to put that together? Certainly never! No one could have written The Slynx except Tatyana Tolstaya!

John Banville has written: “It is impossible to communicate adequately the richness, the exuberance, and the horrid inventiveness of The Slynx.” The man couldn’t be more correct. It is difficult to convey the gaiety and breadth of Tolstaya’s witchy craft. “The Square,” the centerpiece of Aetherial Worlds, is a flashy essay, an irreverent analysis of Kazimir Malevich’s iconic painting The Black Square, linked with a peculiar experience of the great Tolstoy himself and her own labors as a judge on an awards panel for conceptual art. But the collection ends with the story “See the Reverse,” in which a blind man outside a chapel messily consumes a piece of pizza—“fumbling in the dark for that invisible and magnificent sustenance.” Which seems a perfect metaphor for what we crave from a story, and what we receive from this irrepressible, uncorrallable writer.

Joy Williams is the author of The Visiting Privilege: New and Collected Stories (Knopf, 2015) and Ninety-Nine Stories of God (Tin House Books, 2016).