The unnamed narrator of Elfriede Jelinek’s latest novel, Greed, speaks in one voice from multiple minds: She veers from town gossip and amateur sleuth to the royal “we writers”; she then enters the private longings of various Miss Lonelyhearts and the interior monologues of the brutish country policeman who seduces them to gain their property. Like her Austrian forebear Thomas Bernhard, Jelinek has a penchant for loners’ rants and a disgust for her country’s politics. Her premise—that greed corrupts— is classic. Her execution, with its nihilistic digressions, contorted sentences, and “narrative debris,” is maddening.

Kurt Janisch, the policeman, stops women for minor traffic violations, preys on them, and “conquers” them, offering sexual satisfaction in return for their houses. More childlike than manly in his ability to converse and emote, Kurt comes across as a primitive lout, a borderlineautistic stud. The plot is propelled by an “accidental” murder. Villagers try to piece together the mystery; a suicide follows. But this novel has no intrigue. To unravel the chain of events means slogging through the swampland of Jelinek’s prose, which is alternately stupifyingly dull and flecked with brilliance. She will knowingly bore the reader (“You can complain all you like . . . but please not to me”) with long paragraphs about the inadequacies of women and the details of contemporary Austrian politics, then toss off haunting descriptions of the natural world, “where the lake snacks on the tree shadows from the steep shore.” Jelinek seems to connect better with nature than with her characters: Her criticisms of ecological devastation sting, while her portrayal of relationships runs cold.

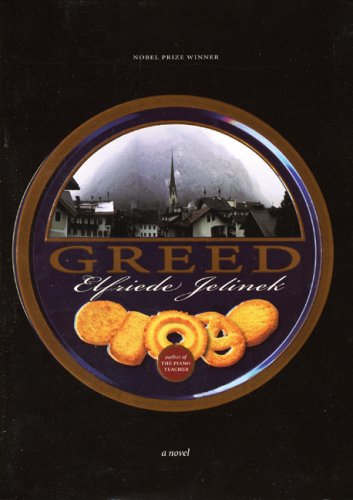

The master-slave structure of the novel is one familiar from Jelinek, who received the 2004 Nobel Prize after the publication of The Piano Teacher (1983), a semiautobiographical novel about a middle-aged woman’s relationship with her overbearing mother and affair with one of her students. The unflinching sadomasochism of that book appears in hollower form in Greed. The policeman maneuvers his “stiff retriever stick” into the “female organism” time and again, but the emptiness is unbearable and the ick factor high. Women are “dessert,” “dirt,” and “holes,” the latter a description that brings to mind the onetime feminist slogan “It’s a muscle, not a hole.”

“No, don’t look the other way,” the narrator taunts the reader. Jelinek seems to disdain the writing process itself, first trying to master it and then submitting to its power over her, thus undermining the story’s emotional core. “I bring everything together once again but, as usual, can’t hold it and let it drop at the last moment, boing.” Throughout, one senses a loss of boundaries, for the characters as well as for the writer.