Described on the back cover as a “stand-alone novel,” Tom LeClair’s Passing Through completes a trilogy begun with Passing Off (1996) and Passing On (2004). It will doubtless appeal most to readers who come to it with a fondness for the protagonist, the author and sometime hero Michael Keever. They will recall Keever as a former point guard in the Greek Basketball Association and the spoiler of an eco-terrorist plot—a plot Passing On revealed to be a fabrication ghostwritten by Keever’s increasingly disgruntled wife.

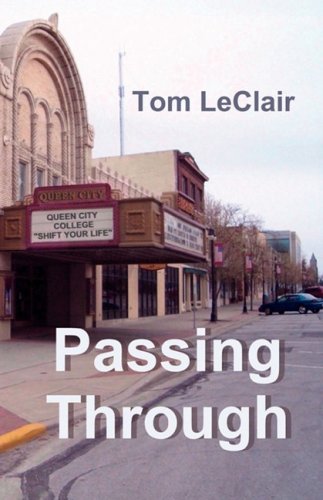

As Passing Through opens, a lawsuit has destroyed Terminal Tours—Keever’s Passing On business of taking the dying on last-request trips—and also his marriage. He has parlayed his first two books into gigs with Hell—a magazine that pays him to “suffer in some shithole,” then return and write it up—and Queen City College, a marginally reputable institution where he teaches travel writing and autobiography for a department whose chair does not believe in the future of books. Keever as adjunct professor allows LeClair, the Nathaniel Ropes Professor of English at the University of Cincinnati, to score a few easy points against higher education and American students handicapped by a sense of entitlement. More important, LeClair’s depiction of Keever—living alone, scrambling for a buck, attempting to outmaneuver a midlife crisis—provides occasions to meditate on the question of whether “we’re all just passing through,” despite a desire to believe that “we go on and on and on.”

We “want to be deceived,” Keever believes, which explains for him not only the appeal of his largely abandoned Catholicism but also his fumbled relationships with his wife, daughter, brother, colleagues, and students. Deception is likewise at the heart of both his writing (travel pieces cobbled together from good intentions and an evening of Googling) and his actions. If the most elaborate deception connected to Passing On occurred outside its pages with LeClair’s creation of an actual Terminal Tours website (terminaltours.com), here it is the author’s appropriation of Algerian feminist Khalida Messaoudi’s autobiography to create a fictional Algerian feminist whom Keever must rescue through unusually risky dissembling.

Some readers may find Passing Through overburdened with what Keever calls “backfilling” (reminders of what happened in the first two books), and others may find the constant use of basketball as explanatory analogy a bit tiresome. The latter gambit at least is defensible, for finally this is a novel about identity, and for Keever, basketball and the dissimulation it requires—its feints and no-look passes—are as inseparable from who he is as truth and lies are indivisible from each other. “I saw ways to liberate my life from fact,” Keever reflects, adding that imagining his story “freed me from my belief that I had been just passing through.” What matters in the end, LeClair seems to wish us to believe, are the memories that “come bouncing back to us” and that “can be passed back” to others. Such sentiments are indeed worth passing along.