Any student of silent cinema, critical theory, and the Frankfurt School, or film aesthetics and the avant-garde, will surely at one point or another have come into contact with the work of Miriam Hansen. Her groundbreaking study Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (1991) inspired a generation of film scholars to place greater emphasis on the ways in which film audiences constitute an alternative public sphere. Likewise, her trenchant essays published over the last few decades in New German Critique, on whose editorial board she served, Critical Inquiry, October, and elsewhere immediately became regarded as required reading—as they still are today—among aspiring film scholars and critical theorists alike; the kinds of essays that prompt serious reflection, frequent citation, and unusually wide dissemination. Above all, her work helped transform the field of American film studies by combining theoretical rigor with far-reaching historical scholarship.

Born in West Germany after the war, Hansen studied at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of Frankfurt in the late 1960s and ’70s, under the tutelage of New German Cinema pioneer Alexander Kluge and the influential German film scholar Karsten Witte. Like many of her classmates in Frankfurt during those years of student unrest, she turned to critical theory, particularly the writings of Theodor W. Adorno and Walter Benjamin, as a source of sustenance and a means of grasping Germany’s tainted past. Soon after finishing her doctoral thesis on Ezra Pound, she emigrated to the United States, where she initially held posts at Yale and Rutgers before joining the faculty at the University of Chicago in 1990. As the Ferdinand Schevill Distinguished Service Professor in the Humanities, she helped establish Chicago’s celebrated Department of Cinema and Media Studies, teaching film history and theory up until her death in February of last year.

During the past decade or so, in the face of a protracted battle with illness, Hansen worked on a project she sometimes referred to as “The Other Frankfurt School,” a highly ambitious study that sought to bring together her abiding interests in Adorno, Benjamin, and Siegfried Kracauer and their respective writings on cinema, mass culture, and the experience of modernity. That project, now posthumously published by the University of California Press as Cinema and Experience, represents the culmination of her intellectual labors, and is a deeply personal undertaking. “I couldn’t fail to realize,” she writes in the book’s preface, finished just a few months before she died, “the extent to which this project was bound up with my own history, a history that entailed switching countries, languages, and fields—from Germany to the United States, from German to English, from the study of literary modernism and the avant-garde to the study of film.”

Divided into four distinct yet overlapping parts, one for each figure (with a final part on Kracauer in exile), the book probes the conceptual terrain unearthed by these three thinkers, all of whom, like Hansen, moved freely—occasionally treacherously and by necessity—across borders, disciplines, languages, and idioms. What links these theorists and their ideas is not just their personal and professional ties (all were of bourgeois German-Jewish backgrounds, all born near the turn of the twentieth century, all friends, colleagues, and devoted interlocutors), but their shared investment in ideas concerning the aesthetic forces of modernity, and how these forces work within mass culture. One of the oft-cited concepts that Hansen introduced, “vernacular modernism,” would seem to apply, at least obliquely, to the exploration that she undertakes here, as it underpins the three scholars’ mutual preoccupation with film as a means of understanding modern experience.

Kracauer, the eldest of Hansen’s composite group, was also the one who engaged the earliest and most exhaustively with the study of motion pictures. He wrote hundreds of movie reviews for Weimar Germany’s newspaper of record, the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung, before publishing his two film books written in the US: From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947) and Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (1960). Owing to the variety of quotidian subjects taken up in his urban reportage (hotel lobbies, sports, radio, the circus, etc.), and to an elegant prose style that Hansen aptly dubs “writerly or poetic,” Kracauer’s Weimar-era feuilletons anticipated the lapidary vignettes in such later works as Roland Barthes’s Mythologies (1957).

Hansen tracks the precise development of Kracauer’s understanding of film, pointing out the different ways in which he revises and adapts his positions over time. For example, in his reading of the so-called Bergfilm, or mountain film, of the 1920s, he initially extols its ability to convey “a delightful optical intoxication,” only later, after fleeing fascism, to lambaste it for the “antirationalism on which the Nazis could capitalize.” Similarly, Hansen shows, in a scrupulously researched and revelatory fashion, how Kracauer’s early writings on photography anticipate his later theory of film and, to a certain extent, prefigure Benjamin’s theoretical reflections in his famous 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.” On a formal level, Kracauer and Benjamin both structure their writing “in the manner of different camera positions or separate takes,” thereby suggesting the fundamental impact of film on their work.

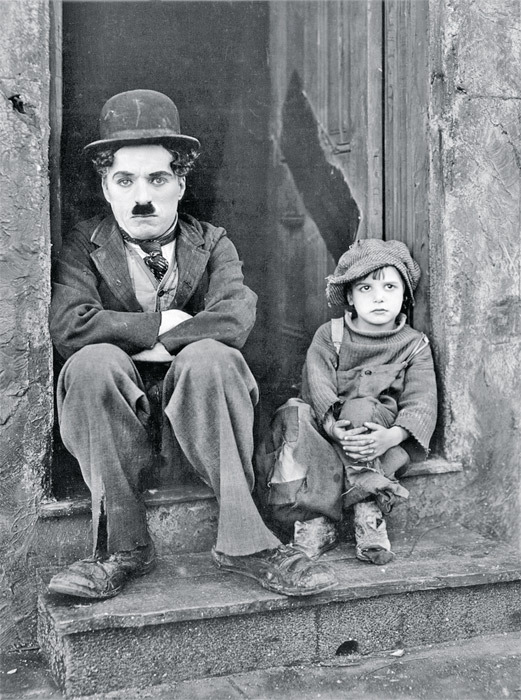

Among the many affinities that Kracauer shared with Benjamin, beyond those strictly of a formal or theoretical nature, was a mutual appreciation of Chaplin, slapstick comedy, and Disney. (The notably less film-friendly Adorno reserved his admiration for the Marx Brothers.) For Benjamin, Chaplin was the great champion of the disinherited, a prophet of alienation, and a window onto the modern condition, making him, among other things, the perfect “key to the interpretation of Kafka.” Likewise, Kracauer considers Chaplin a “diasporic figure,” a “pariah” (slightly at odds with Adorno’s more abstract, less affirmative understanding of the Little Tramp as “a ghostly [or haunting] photograph in the live film”).

The connections between writing film criticism and cultural theory and these scholar’s everyday lives as uprooted intellectuals are frequently palpable. “The leitmotif of slapstick comedy,” writes Kracauer, “is the play with danger, with catastrophe, and its prevention in the nick of time.” As for the significance of Disney, Hansen devotes a chapter to Benjamin’s writing on Mickey Mouse, noting early on that what he saw as the principal appeal of these cartoons, much like the appeal of Kafka or Chaplin, was “the fact that the audience recognizes its own life in them.” In a similar vein, Benjamin elucidated a strong connection between Hollywood cartoons and the German fairy tale (and, by extension, between American popular culture and German high culture): “All Mickey Mouse films are founded on the motif of leaving home in order to learn the meaning of fear.” Hansen subtly foregrounds such discursive links without overstating them.

The section on Benjamin forms the core of Hansen’s work, taking up five of the book’s nine chapters. Here she wrestles with some of Benjamin’s most enigmatic concepts, including the notion of aura that he developed in his most famous essay. Somewhat akin to his ambivalent position regarding modern experience—embracing the innovations of new media (photography, film, radio, etc.) and their potential to transform, even to liquidate, past notions of autonomous art, while also bemoaning the atrophy of experience in the face of such technological advances—aura crops up in a number of competing and occasionally contradictory guises in Benjamin’s opus (it is likened, in his hashish experiments, to late van Gogh paintings or, in his “Little History of Photography,” to a seemingly Romantic, quasi-mystical experience of nature). As Hansen puts it:

Aura is a medium that envelops and physically connects—and thus blurs the boundaries between—subject and object, suggesting a sensorial, embodied mode of perception. One need only cursorily recall the biblical and mystical connotations of breath and breathing to understand that this mode of perception involves surrender to the object as other.

Hansen’s nuanced reading of Benjamin reveals her extraordinary erudition, and suggests the command of someone who has spent decades digesting these occasionally knotty texts.

Writing on Adorno, whose lectures she attended as a student, Hansen cautions her readers against a too-easy dismissal of his position on mass culture as “mandarin, conservative, and myopic.” Adorno’s notoriously allergic reaction to jazz, not to mention his powerful invective against the “culture industry” in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), should not discount him from being considered a shrewd and perceptive interpreter of film. Although he didn’t write on the subject with anywhere near the same sustained commitment as Kracauer, nor with the same vital curiosity as Benjamin, Adorno offered several provocative critiques of the medium. Fleetingly, and surprisingly, during the early phase of New German Cinema in the early ’60s, Adorno expressed “hope that the so-called mass media might eventually become something different.” While he never showed much affection for the movies (Kluge once quipped that Adorno’s opinion of film could be summarized as “I love to go to the cinema; the only thing that bothers me is the image on the screen”), he weighed in on theoretical debates concerning montage, the principles of realism and the avant-garde, and “the neutralization and abstraction of time in mass culture.”

The occasional density of Hansen’s prose is not unlike that of Adorno’s—who famously defended the merits of rigorous forms of philosophical inquiry. Hansen’s work tacitly subscribes to this notion, though the effort she demands of her reader is amply rewarded by the rich suggestiveness and expansive quality of her insights. Those students who’ve had the pleasure of becoming acquainted with Hansen’s work, as well as those who have not, stand to benefit considerably from the publication of this final work, a crowning achievement in its own right.

Noah Isenberg directs the Screen Studies program at Eugene Lang College—The New School for Liberal Arts.