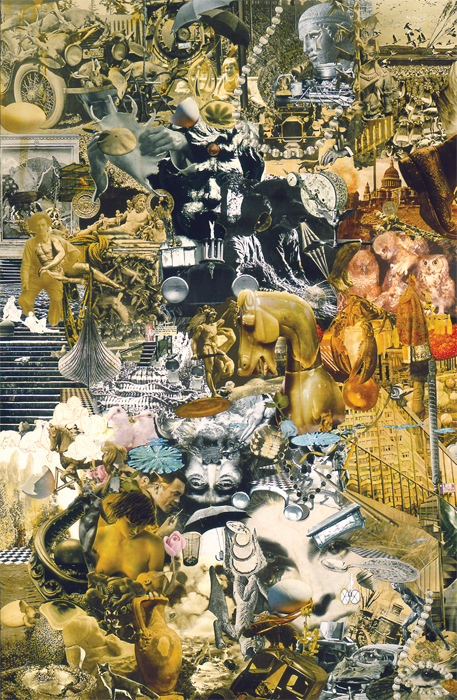

Few contemporary artists meaningfully engage with poetry in their work. When they do—whether it is Anselm Kiefer enlisting Paul Celan, or Nancy Spero ventriloquizing Artaud—they tend to prefer their poets dead. It is all the more remarkable, then, that the painter and collage artist Jess (1923–2004) and his partner of nearly forty years, poet Robert Duncan (1919–1988), collaborated frequently and made each other’s ideas fundamental to their art. Duncan and Jess attracted a diverse group of Bay Area artists and poets, and this milieu is the subject of An Opening of the Field: Jess, Robert Duncan, and Their Circle (Pomegranate, $65), by Michael Duncan (not related to the poet) and Christopher Wagstaff. Duncan also edited and introduced a recently published collection of Jess’s collages, Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica (Siglio Press, $48). An Opening of the Field is earnest and old fashioned (in the best sense); there are some small flaws (too little attention to the relative sizes of the artworks in the reproductions), but overall this is a revelatory volume, assembling work by artists, some forgotten, others prominent (Llyn Foulkes, R. B. Kitaj), and by poets including Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Michael McClure, to re-create a seminal moment in postwar culture.

An irresistible story animates Converging Lines: Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt (Blanton Museum of Art/Yale, $35): the warm friendship and mutual influence of artists with almost diametrically opposed sensibilities—made especially poignant by Hesse’s early death. Her formal debt to LeWitt is easily demonstrated, but the book fails to clinch curator Veronica Roberts’s thesis that LeWitt’s work was significantly shaped by Hesse. Lucy Lippard’s brief, focused contribution to the book begins by addressing the questions in the back of our mind: Yes, LeWitt was “wowed” by the artist, eight years his junior, when they met at the end of the 1950s; no, the sentiment was not reciprocated. Nevertheless, LeWitt, with his customary generosity, supported her career, and their mutual respect enabled a productive dialogue. An image of an oft-quoted 1965 letter from LeWitt to Hesse conveys the flavor of their correspondence, as he responds to her expressions of self-criticism with sage advice: “Learn to say ‘Fuck you’ to the world once in a while. . . . Just stop thinking, worrying, looking over your shoulder . . . mumbling, bumbling, grumbling, humbling, stumbling”—this goes on for a while—“Stop it and just DO.” Mel Bochner, quoted in Lippard’s 1976 Eva Hesse (still the best monograph on a contemporary American artist), says that what Hesse got from LeWitt was “the same thing I got, which was a sense of ordered purposefulness. You did your work as clearly as you could; what you didn’t know, you made apparent you didn’t know. That’s a lot more important than maybe it sounds.”

Richard Serra was a kind of god for a certain generation of young artist: In the early 1970s, they all would have Grégoire Müller’s The New Avant-Garde (devoted entirely to male artists, of course) on their shelves, with its cover image of Serra, wearing a respiratory mask, about to fling hot lead, like Jupiter hurling a thunderbolt. The impressively realized Richard Serra: Early Work (David Zwirner/Steidl, $85) identifies the occasion of that famous photo: Serra installing an exhibition of his work at the Castelli Warehouse in 1969—a show that featured Serra’s Casting with Four Molds, to Eva Hesse, a tribute consisting of multiple hardened shapes from each mold and covering approximately thirty by thirty feet. Among the sculptors who emerged beside Hesse in the 1960s, Serra shared specific formal and emotional qualities with her—intense physicality and attraction to unorthodox materials, but also a certain cheekiness and dramatic self-expression—which make them a more natural aesthetic pairing than Hesse and LeWitt. Formal echoes abound between her pieces and Serra’s between 1967 and 1969. This new volume focuses on Serra’s production from 1966 to 1971, each year’s work followed by reviews and writings that give us a blow-by-blow account of Serra’s rapidly expanding art-world presence. The book’s mainly black-and-white photography conveys the gravitas of Serra’s art, and even hints at a paradoxical lightness and humor, which is often lost in the overbearing scale of his later sculpture.

Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale, $50) accompanies the Met’s first exhibition solely devoted to contemporary Chinese art. Installed in the museum’s galleries for Asian painting and calligraphy, the show presents a tranche of works made by mainland Chinese artists since the 1980s that is both too narrow (it omits the great majority of recent Chinese artists working in ink by focusing on those who practice shiyan shuimo, or experimental ink painting) and too broad, including sculpture and even furniture, which has, in the words of curator Maxwell K. Hearn, “an underlying identification with the expressive language of ink art.” One gets a sense that the Met is coming late to the party: Many of the choices of avant-garde art reproduced here are quite familiar, and some of the work that isn’t as well known, while technically impressive, seems merely illustrative or conceptually thin.

For every art form today, there must be an “outsider,” and Chinese calligraphic art is no exception. The King of Kowloon: The Art of Tsang Tsou-choi (Damiani, $50), edited by David Spalding, preserves a significant selection of works by the street artist Tsang Tsou-choi (1921–2007), the self-described ruler of Kowloon, a district of Hong Kong. Over some forty years, Tsang, who supported himself as a garbage collector, was a familiar figure in Hong Kong, but it was only during his final decade that he gained attention from the art and fashion worlds, and became a kind of mascot of the city, with his face and calligraphy seen on T-shirts and stenciled street art. This beautifully designed book—with boards, an exposed paper spine, and trimmed text-block edges all printed with reproductions of Tsang’s lively calligraphy—aptly represents his monomania. Often taking the form of Chinese ancestral records, Tsang’s calligraphy typically presented him as an emperor—of Hong Kong, perhaps, or all of China—or even occasionally as the Queen of England. A cleverly designed guide to key terms in his street works allows readers without Chinese to gain a sense of how Tsang’s work may be decoded.

“Part of the allure of Mendieta’s work,” writes Adrian Heathfield in Ana Mendieta: Traces (Hayward/Artbook DAP, $40), “arises from its striking nonconformity. It is difficult to name and locate her practice in the established narratives of Western art history relating to the 1970s and ’80s.” This credulous statement is characteristic of the book, accompanying the first full retrospective of Mendieta in the UK, which attempts to present her as a kind of unique, meteoric figure, in large part by uncritically buying into her own carefully constructed mythology. But Mendieta’s fascination derives exactly from her status as a university-honed professional, whose training in the University of Iowa’s pioneering Intermedia Program was preceded by serious study of ancient cultures, including field trips to Mexico. Cannily drawing on art history as well as a network of contemporary artists who are now canonical, she synthesized a potent model of artmaking, meticulously planning and documenting her tableaux and ephemeral sculptures. In her tragically brief New York career, she achieved a highly focused and distinctive body of work, represented by the photographs seen here, though the sometimes murky reproductions on uncoated, off-white paper stock do the images no favors.

The vertiginous image on the cover of Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe (Guggenheim Museum, $60), reproducing Tullio Crali’s 1939 painting Before the Parachute Opens, announces that this book will go where studies of Futurism typically have not gone: past the heady years of the early teens, with the trademark paintings of dynamic action, into the darker realms of the movement’s attempt to accommodate fascism’s rise, and up to the death of its founder, F. T. Marinetti, in 1944. Faced with a body of work that encompasses fine-art media but also architecture, graphics, photography, sound, poetry, performance, and music (I must be leaving something out), editor Vivien Greene—who organized the show and shepherded this project over some seven years with the aid of an eminent advisory committee, many of them among the book’s thirty authors—made the wise decision to adopt what might be called a faceted approach. Brief essays alternate with portfolios illustrating their topics, allowing one to move around and through the vast subject without being overwhelmed. The book doesn’t shy away from examining Futurism’s striking contradictions; along with its disturbing glorification of violence and contempt for women, for example, there is a surprisingly democratic, Beuys-like faith in the everyman’s creative potential. One might expect a wild parole in libertà layout, but veteran designer Eileen Boxer instead offers quite restrained, readable spreads that give the lively works a generous stage.

Christopher Lyon is executive editor of the Monacelli Press.