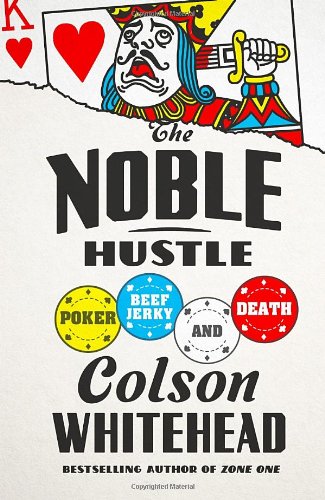

There are three decent books about the World Series of Poker. Al Alvarez’s The Biggest Game in Town recounts the first World Series held at Binion’s in Las Vegas in 1981—a ragtag gathering of clever cowboys jousting with one another for bragging rights. James McManus’s Positively Fifth Street captures the breaking wave in 2000, when the poker fad was expanding exponentially, the cowboys were sliding back into the foamy soup, and the bourgeois techies and digital corporations were rising into ascendancy. The book under review here, Colson Whitehead’s The Noble Hustle: Poker, Beef Jerky, and Death (Doubleday, $25), presents the corporate apotheosis of the 2011 World Series of Poker in golden light, as if the wave were on the beach at sunset.

All of these books began as magazine assignments, and they give us what magazine writing should—the ambience, the local color, the cast of characters, and the feel of things. What they tell us about poker is terminally skewed by the eccentricities of tournament poker and the innocence of magazine writers. It suffices here to note that all of these writers are drawn to poker by the risk and spectacle, but none with a high heart. Tremulous anxiety sucks up the pages. The wives and kids back home, whose livelihood poker places in jeopardy, are much in evidence, too—as are “friendly” games in college that lay a bad foundation, since poker is not a friendly game, or a personal game.

Simple truth: The more you know about your opponents, the less you know about their play, because poker is not self-expression. It’s all hustle and dazzle. Every poker player has a deceptive poker persona and an even more deceptive game. I know hard-ass wise guys who play like anxious librarians, and anxious librarians who will whack you off at the knees. So trust this: Any personality you detect within a hundred yards of a poker game is guaranteed fiction. Nothing you see at a card table is authentic except the cards face up on the table. Little Stukey is wearing a hoodie at the table because he doesn’t want you to see his ears turn red. Drago Burns is wearing a beige turtleneck and keeping his hands in his lap because he doesn’t want you to read the pulse in his neck or the pressure of his forearms on the table. These outfits and behaviors are distractions that serious players do best to ignore.

But there’s a difference between real players and writers: Writers can’t ignore these distractions. This is why Whitehead et al. approach their subject as “soldiers of poker,” slogging along, believing their eyes and thinking with their hearts. The poker table is the most dangerous place they’ve ever been, so they talk of war and battle. Whitehead has some justification, since, early in the tournament, he gets shot down on the river like a recon grunt. But for the real players, the “pirates of poker,” the poker table is the safest place they’ve ever been. They play the abstract game, and they are not crippled with angst and regret.

They are, overall, the winners, and this, too, distinguishes them from the writers who observe them. Winners’ narratives are not so book-worthy. Losers are always more interesting, and in the loser category The Noble Hustle is by far the best, since Whitehead luxuriates in his depression. He claims to hail from the Republic of Anhedonia (“an-he-do-nia: the inability to experience pleasure”). From his text we infer that Whitehead hopes that pleasure might fall upon him like dew in the arena of fatal options. It doesn’t, of course.

And why would it? Whitehead, again like a writer, tells us too much. He tells us about the time he stumbled upon an antique store where everything looked as if it had been left out in the rain and admits that he likes to buy furniture that reminds him of himself. And what can you say about a player who prowls the fleshpots of Vegas and happily falls upon the House of Jerky on Fremont Street—an institution whose goals are simple and clearly in evidence. Connoisseur of duplicity? Not a chance. Poker hero? I don’t think so. Joyless kamikaze? Closer. Brave? Certainly. Interesting? Yes, in a Dostoyevsky sort of way. And even if he’s the wrong guy for big-stakes card playing, he’s the right guy to write about it. Because of his timorous writing persona, he is very good on tournament poker’s cruelest mandate: the imperative that you must win it all or lose all your chips in a long, slow slide into oblivion. (There are prizes for finalists, of course, but you still have to lose to win them.)

In a real poker game, when you find yourself with enough chips to play but not enough chips to win, you cash out. You stroll over to Lutèce and have a nice dinner. Quitting is always an option when your stack diminishes. When your opponents are too good or too bad to get a read on, you quit. Also, poker is not basketball. If you’re up twenty at the half, or down twenty, you can bail. The game goes on forever. You jump in. You jump out.

Not so in tournament poker. You sit there with your short stack and get your balls crushed. It’s like a gang initiation, and you’re a player, so you must try to win. So you play hands that you shouldn’t. You play players that you shouldn’t, and, finally, having lost, you don’t hate yourself for losing the money, you hate all the stupid poker you played. This is very depressing, and Colson Whitehead catches the anomie and helplessness perfectly.

This is why, after twenty-five years in Las Vegas playing poker, I have never even been near a tournament. They sound like graduate school. You fill out the forms they tell you to. You study the big, statistical poker books. (My favorite is David Sklansky’s Theory of Poker—but, then again, I like Derrida.) Thus prepared, you start playing when they tell you to. You stop when they tell you. Your game goes on videotape, which scares the hell out of me. You eat when they tell you to—play the table they tell you to against the opponents they tell you to. You wear what they tell you to and smell your opponents whether you want to or not, because tournament rooms get ripe, I’m told. All this is to comply with a stupid pop-culture narrative that, from a cost-benefit perspective, is a waste of table time, and has nothing to do with poker, which is a game of vectors and numbers.

In Vegas, I always favor nontournament poker because you have so many more options, defaults, and refusals. You get to pick your own brand of anxiety from a menu of options laid out amid the numbers and the angles of approach. There is no magic. There are fifty-two cards in the deck. There are ten positions around the table, each of which has its own perils and advantages. In pot-limit Hold’em, which is what I play, there is usually about $200K in the game, about two thousand chips. One glance at the numbers tells you to forget the cards. There are too many of them, and too many sets of pairs, suits, and sequences. The cards just happen, and you deal with them on the fly. Doyle Brunson claims he can win without looking at them. I look at my cards, but I play the constants: my nine opponents and the optimum positions.

My friend Curley used to open for acts on the Strip with a lobster joke that’s relevant to poker. “So I’m standing in front of this giant lobster tank,” Curley would say, “and you’re supposed to pick the lobster you want them to kill, but I don’t know dick about lobsters. So what do I do? I just stand there until one of those lobsters really pisses me off.” The joke encapsulates my everyday poker philosophy. I just sit there until one or two of my opponents really piss me off because they don’t know how to play. I play these dudes, and fuck the poker gods. These guys are an offense to the game. They’re going home tomorrow. They want some action, and if I can, I give it to them with bluffs, check-raises, and four-bets. For these guys, poker is not a war. It’s a means of assisted suicide, because, for reasons I have never fathomed, these guys want to lose. Knowing this hardens your heart, but the game is still fun once the turkey herd is thinned.

So why read books about tournament poker? To warn yourself against it, of course. And also because tournament poker has a narrative that is totally bogus but still useful to journalists. It’s got personalities that are little more than commedia dell’arte, but they are catnip for writers. Tournament poker is made to be written about, because we all love stories of folly, dashed hopes, cruel dismissals, and moral fecklessness. Compared with this great drama, three days of ordinary poker is tapioca. Just ebb and flow, little jokes, little victories, quiet people, handsome women, and French food. Tournament poker, however, has taken on talismanic status. Along with day trading, it’s our mercantile quest for the dragon. It is overregulated and unfair, but so are our lives. It is not in the least alien, not anything like freedom.

Whitehead’s book captures this manic Jonestown reenactment as well as any book I’ve read about the game. The Noble Hustle, with the suicide King of Hearts on the cover, has the feel of a book written quickly—not to save time, but to let the truth slip out unawares when it can, with whatever feeling it might bear with it, and poker is a good subject upon which things might slip out. Like Willie Nelson’s face, poker is anything you want it to be. It can be lawn darts or an abattoir. For Whitehead, the game is an artist’s ploy. He is looking aside from death, his true dark subject, in the hope of actually glimpsing it. In Vegas, he just may have.

Dave Hickey’s most recent book is Pirates and Farmers: Essays on Taste (Ram Publications, 2013).