THERE'S SOMETHING endearing about people who loudly proclaim their love of books. Forget the suspicions kicked up by trumpeting something as universal as “books” as one’s true love (also loves: baby animals, pizza, oxygen); forget the anachronism of loving physical objects in space and not some “long read” floating in the ether; forget the self-congratulatory tone that hints at a closetful of book-festival tote bags emblazoned with Shakespeare’s face. Proudly championing books still counts as a true act of courage, a way of raging against the dying of the page.

In embracing the book as an object, a concept, a signifier, and a religion, though, one often forgets the texts that answer to the name of “book” these days. A perusal of the best-seller lists of the past two decades indicates that the most popular books might more accurately be described as billionaire-themed smut, extended blast of own-horn tooting, Sociology 101 textbook with sexy one-word title, unfocused partisan rant, 250-page-long stand-up routine, text version of Muppets Most Wanted with self-serious humans where the Muppets should be, folksy Christian sci-fi/fantasy, pseudohistorical rambling by non-historian, and simpleton wisdom trussed up in overpriced yoga pants.

And if we narrow our focus to the No. 1 spot on the New York Times’ hardcover-nonfiction best-seller list in the twenty years since Bookforum was first published, we discover an increasingly shrill, two-decade-long cry for help from the American people. As I Want to Tell You by O. J. Simpson (1995) and The Royals by Kitty Kelley (1997) yield to Dude, Where’s My Country? by Michael Moore (2003) and Plan of Attack by Bob Woodward (2004), you can almost see the support beams of the American dream tumbling sideways, the illusions of endless peace and rapidly compounding prosperity crumbling along with it. The leisurely service-economy daydreams of the late ’90s left us plenty of time to spend Tuesdays with Morrie and muse about The Millionaire Next Door or get worked up about The Day Diana Died. But such luxe distractions gave way to The Age of Turbulence, as our smug belief in the good life was crushed under the weight of 9/11, the Great Recession, and several murky and seemingly endless wars. Suddenly the world looked Hot, Flat, and Crowded, with the aggressively nostalgic waging an all-out Assault on Reason. In such a Culture of Corruption, if you weren’t Going Rogue you inevitably found yourself Arguing with Idiots.

Tracking this borderline-hysterical parade of titles can feel like watching America lose its religion in slow motion. Except, of course, this also meant there was a boom industry in patiently teaching faith-shaken Americans precisely how to believe again. Since the new century began, the top spot on the best-seller list most years has been all but reserved for these morale-boosting bromides: Seemingly every politician, blowhard, and mouthpiece willing to instruct us on how to reclaim our threadbare security blanket of patriotism, cultural supremacy, and never-ending growth and prosperity has turned up in that prestigious limelight. If that list is any indication, we’re desperate for something to ease our fears—or to feed directly into those fears with the kind of angry rhetoric that plays so well on cable news.

It makes simple sense, then, that the most popular nonfiction authors of our day might be characterized by a certain overconfident swagger, the modern prerequisite for mattering in a mixed-up, insecure world. More often than not, these “authors” aren’t authors at all, in the strict sense of carefully pondering their ideas and diction and lovingly crafting an argument sturdy yet supple enough to carry their work over to a mass readership. In place of the William Whytes, Vance Packards, and Betty Friedans of earlier, more confident chapters of our national bestsellerdom, we have promoted a generation of alternately jumpy and anxious shouters. Generally, these public figurines fall into one of two categories: television personalities who have hired hands to cobble together their sound bites; and middling nonwriters suffering from extended delusions of grandeur. When it comes to hardcover nonfiction, a realm in which (for now at least) books often are physical objects, plunked down on coffee tables as signifiers or comfort totems, Americans don’t seem to be looking for authors or writers or artists so much as lifestyle brands in human form: placeholder thinkers whose outrage, sense of irony, or general dystopian worldview matches their own, whether it’s Glenn Beck, Barack Obama, or Chelsea Handler.

It’s a glum corollary of such market forces that these very popular nonfiction books aren’t books in the traditional sense of the word so much as aspirational impulse buys. They imbue their owners with a feeling of achievement and well-being upon purchase, a feeling that crucially does not require the purchaser to actually sit and read the book in question. Substantive, thoughtful books might pervade other lists (e-book, trade paperback, etc.), but when it comes to the top position on the hardcover-nonfiction roster, accessory books by high-profile bloviators typically dominate, from Al Franken’s Rush Limbaugh Is a Big Fat Idiot to Ann Coulter’s Godless to Edward Klein’s The Amateur to Dinesh D’Souza’s America.

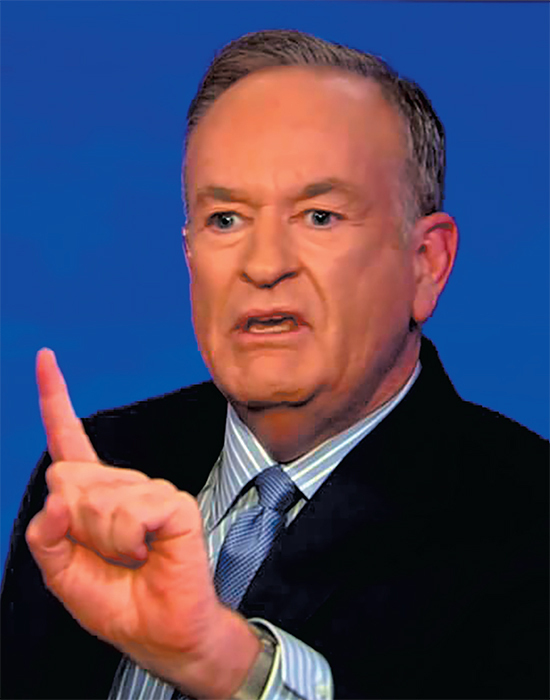

And while it’s impossible to argue that people aren’t purchasing books by Laura Ingraham and Sean Hannity and Sarah Palin and Dick Cheney, it’s also difficult to imagine that people are actually reading these books from cover to cover. These are identity accessories more than books—the red-state equivalent of what a funky watch or rakishly arranged silk scarf might be in our notoriously shallow and decadent coastal metropolises. It also says something about the current state of liberal culture that the most popular blue-state authors—Franken, Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert—are, accessory-wise, more like a bow tie that squirts water in your face. Solemn, poorly written tomes on everything that’s wrong with this country are on one side of the fence, ironic detachment, incredulity, and clown cars on the other. Or as Bill O’Reilly put it when he appeared on the Daily Show in 2004, “You’ve got stoned slackers watching your dopey show every night, and they can vote.”

Bemoaning the stoned slackers of the world might not be a wise choice for the author responsible for what we might term the “Mansplanations of History for Stoned Slackers” series: Killing Lincoln (2011), Killing Kennedy (2012), Killing Jesus (2013), and Killing Patton (2014), every single one of which rested comfortably in the No. 1 spot for weeks at a time. In fact, over the past two decades, O’Reilly has been in the position with seven different books for forty-eight weeks total. How does he do it?

Here’s a clue: If mansplaining means “to comment on or explain something to a woman in a condescending, overconfident, and often inaccurate or oversimplified manner,” then O’Reilly clearly sees America as a suggestible (though fortunately profligate) woman in desperate need of a seemingly limitless amount of remedial mansplanation. And to be fair, if the most popular nonfiction books are a reliable guide, Americans crave mansplaining the way starving rats crave half-eaten hamburgers. We’d like Beck—not an education professor—to mansplain the Common Core to us. We want Malcolm Gladwell—not a neuroscientist or a sociologist or psychologist—to mansplain everything from the laws of romantic attraction to epidemiology. And we want O’Reilly—not an actual historian—to mansplain Lincoln, Kennedy, Jesus, and all of the other great mansplaining icons of history. We want mansplainers mansplaining other mansplainers. We dig hot mansplainer-on-mansplainer action.

Mostly, though, what Americans seem to want, based on our hardcover purchases, is some way to beg, borrow, or steal our way back to the good life. We want someone to blame. We want someone to fix things. Republicans have capitalized most effectively on this longing, and have gained far more leverage from it over the years than Democrats, because they trust former neurosurgeons, TV-talk-show hosts, bloggers, radio personalities, and pretty much anyone who’s ever appeared on Fox News to hold forth on the lost American dream. Whom do Democrats trust? Current or former presidents, current or former first ladies, and . . . comedians. On the Right, pretty much anyone with a bad temper is welcomed into the fray. On the Left, you’d better be on TV, but only CSPAN or Comedy Central will do.

It’s unclear how the toxically partisan mansplaining tome became the go-to hardcover-nonfiction best seller when obviously there are many other varieties of best-selling nonfiction in the sea: the folksy yarns packed with down-home wisdom (Tuesdays with Morrie), the “God Is My Copilot” tomes (Conversations with God, Heaven Is for Real, Proof of Heaven), the no less zealous “Dog Is My Copilot” titles (Marley & Me, Inside of a Dog), the detailed retellings of historical events (Unbroken, The Boys in the Boat), and the managerial talismans (Who Moved My Cheese?). Such titles still fit the bill as aspirational accessories, with one important caveat: People actually seem to read them. It may be a presumptuous observation, or just an intuition, but those hardcover copies of It Takes a Village and Decision Points and The Way Forward usually look pristine and immovable in their hallowed roles as oversize paperweights or propagandist doorstops, whereas the average copy of The Four Agreements looks like it’s been through a few dozen washing-machine cycles.

And it’s telling that such books are often segregated onto separate lists. The New York Times has a business-book best-seller list and an “Advice, How-To & Miscellaneous” list, presumably to shine more glory on, say, Walter Isaacson than on the author of 10-Day Green Smoothie Cleanse. Still, the wide gap between what people will tell you they’re reading (shiny hardcovers, good mostly for a few cocktail-party talking points) and what they’re actually reading (a dog-eared copy of Quiet) underscores a central strain of the public/private interface in American life. Other nations may perceive us as hopelessly frank and confessional, but the reality of stateside social dynamics is much more of a Jekyll-and-Hyde affair, in which a polished professional pretends to be preoccupied with solemn sociopolitical concerns while privately obsessing over love, personal empowerment, and green-smoothie diets.

What is the source of our shame, exactly? Perhaps that the much-heralded partisan mansplainers of the hardcover list—women among them—may be some of the most unfit writers ever to put pen to paper (“I started running again, and it wasn’t long before I started feeling pretty good, because I started thinking about some pretty good things.” —Sarah Palin, Going Rogue). Thoughtful, poetic nonfiction writers are sequestered in the paperback, e-book, and “how-to” ghetto because it’s somehow more respectable to craft digressive, empty tomes that essentially consist of reshuffling fifteen key words over and over again—freedom, liberty, solutions, leadership, founding principles, prosperity—until writer and reader alike chew their own paws off just to escape the steel trap of syntactic pandering.

The easiest explanation is that a newly enfeebled America craves mansplanations and shuns humility. Humility conjures falling stock prices and ineffectual wars and citizens who don’t feel proud so much as desperate, and maybe even a little embarrassed—by Enron, by Katrina, by Ferguson, by the 101 cruel missteps of the past two decades. Humility is a woman thing, and by the hectoring logic of our mansplaining franchises, woman things are almost always embarrassing and bad. Novels by women are chick lit. Essays by women are “girl-friendly tales.” Professional journalists are mommy bloggers. Man things deserve shiny hardcovers and pride of place on the coffee table. Woman things get flimsy covers with cursive writing and a leopard-print high heel illustrated on them, and they’re shoved into purses and nightstand drawers. Humility and self-reflection are for the weak or silly.

But there’s a key, and revealing, development overlooked amid this division of culture-saving labor. Many of these theoretically insignificant paperbacks aren’t just embraced in the truest, pored-over, book-lover sense of the word; they’re arguably more popular over time than a five-hundred-page political doorstop. The Hite Report, Shere Hite’s detailed examination of female sexuality, may represent the ultimate in softcover ubiquity: Hite’s publisher originally printed two thousand copies, mansplaining to her that “people are tired of feminism and sex.” Since then, fifty million copies have sold worldwide. Hite’s book, and others quietly acclaimed by women en masse, suggests that a more private story of American life is unfolding on the margins of the hardcover list, and humility and self-reflection are the central words in play there.

Although The Hite Report may have represented a beacon of liberation that was soon clouded over by a storm of regressive books like Women Who Love Too Much (1985), the arc of the best-selling universe may be bending toward liberation once again. Since the nadir of The Rules (1995), which instructed women to imitate nonchalant, overscheduled alien life-forms in order to lure unsuspecting human males onto the marital mother ship, one senses a slow, grueling march to empowerment in the paperback best-seller list, not unlike the slow, grueling march recounted by Cheryl Strayed in her omnipresent best seller Wild (2012). Because, despite a few undeniable low points (Marry Him!, To Hell With All That), some of the most popular softcover books being stuffed into shoulder bags and nightstands—How to Be a Woman, The Liars’ Club, Bossypants, and, yes, Eat, Pray, Love—mark a dynamic and surefooted departure from the blind swagger of hardcover mansplanation. Instead of listening to men, serving men, tagging and tracking a suitable man, or parroting mansplanation after mansplanation in order to peacefully sally forth in a man’s world, many female authors are serving up unique prose about finding gratification and solitude against a backdrop of global chaos. Even Lean In, in all of its One Percenter Mansplains Work-Life Balance to the Rest of Us absurdity, represents a genuine attempt to encourage women not to succumb to the domestic undertow of the zeitgeist. No matter how many dozens of handservants Sheryl Sandberg leans on in order to facilitate her own leaning in, her message—that fulfilling work makes a woman’s life better—is worthwhile, if depressingly exotic.

The guardians of the status quo will continue working assiduously to protect so-called elite turf, waving off paperbacks and e-books and self-published books as if the real interests of the reading public weren’t good enough for the sacred hardcover ground occupied by vainglorious celebrities and TV-talk-show blowhards. But in the shadow of the hardcover best-seller list, there is a much wider and more varied universe of writers and readers. Whether these titles are purchased at a store, downloaded onto phones and e-readers, delivered by Jeff Bezos’s drones, or carved into stone in some blurry dystopian future, original thinkers will keep writing them, and book lovers will find a way to read them.

Heather Havrilesky is the author of the memoir Disaster Preparedness (Riverhead, 2010).